Breathing Success – Mario Moretti Polegato “Geox”

June 20, 2011No Escape

June 20, 2011By Christopher Thompson

The newsagent on London’s Battersea Park Road resembled any other small business that predominates along the city thoroughfare. Small, cramped with foodstuffs whose labels read in Polish or Arabic, and owned independently by an immigrant family whose extended members work behind the till. But next to the phone cards promising the cheapest rates on three continents, there’s a hand-written sign which advertises a unique service to the more discerning émigré. Hawala – a Muslim money-transfer service – deals in the tens of millions of pounds each year that flow in and out of Somalia, the world’s most lawless country. “Hawala is like our Western Union – you can transfer anywhere in the world in minutes, no matter if there are banks or not,” said Mohamed, the cashier, originally from Mogadishu, Somalia’s anarchic capital. It’s also the transfer method of choice for Somali pirates who, according to experts, are using some of the same south London convenience stores to launder booty captured on the high seas.

Since 2007 Somalia has become the world’s unofficial pirate capital. According to the East African Seafarers Association (EASA) there were 152 Somali pirate attacks last year – three-quarters of Africa’s total – despite a massive increase in foreign navy patrols. The United Nations envoy to Somalia, Ahmedou Ould Abdallah, estimates that piracy now brings in US$120 million annually, several times the official national budget and a significant proportion of the US$1 billion in remittances which flow each year between Somalia and the diaspora populations in Britain, the United States, Sweden and the Gulf. Some of that is re-invested locally in businesses, shops and shimmering 4x4s that line the streets of Bosaso, the pirates’ main port. But most goes abroad, to pay-back the syndicates who fund the attacks and the pirates’ family members who profit from the spoils.

“What happens to the money is exceedingly opaque, partly because of the way Somalis communicate with each other, and also because of the impenetrable way their finance system works,” said Christopher Ledger, a former a former Royal Marine officer and maritime security expert.

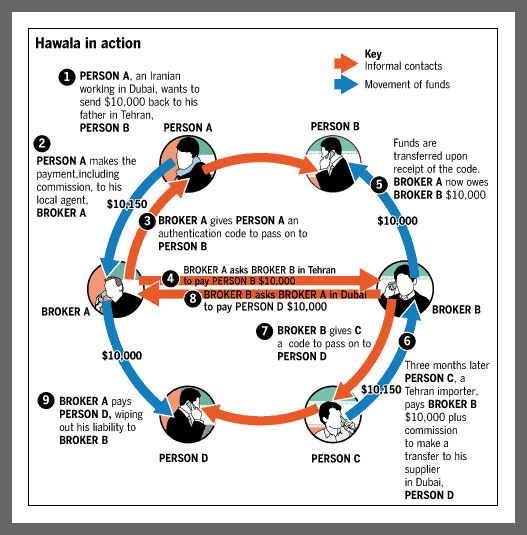

Hawala – literally ‘transfer’ in Arabic – originated from the word ‘ha-wil’ meaning to transform or to change. Since it doesn’t use promissory notes there’s no paper trail; hawala moves under the radar of regulators using a method as old as trade itself. Hawaladars – the people who conduct the transfers – will have a book of contacts across the regions in which they conduct business. If Ali in Somalia wants to transfer £5000 to a cousin in Birmingham, he will approach a hawaladar who operates there. As the money will not immediately leave the country, the hawaladar finds a corresponding partner with enough liquidity to finance the transaction. The system operates on kinship ties and trust, using clan-based allegiances to ensure near instant transfers. The ‘debt’ owed to the hawaladar in Birmingham is noted on a ledger and will be paid back at a later date, usually subtracted from a transfer in the opposite direction. Although identifying information includes details of clan membership, traditional networks now include online money transfers and mobile-phone banking. Rates are rarely discussed. Firstly, few registered money agencies will send funds to Somalia. Secondly, hawala rates will almost always be better than the formal competition. To send £1,500 from Battersea to Mogadishu I was quoted a commission of £40, less than the price of sending the same sum from London to Lisbon with Moneygram or Western Union.

Three thousand miles east of Battersea lies tropical Mombasa, Kenya’s second biggest city and its major port. The storage depots and family run bakeries that line the streets in Mombasa’s Somali-dominated Kingorani suburb don’t mark it out as a place for pirate investment. But it’s neighbourhoods like these where much ransom money is moved so it can be laundered in the ‘real’ economy and – if desired – transferred onto the west.

Over the past three years so much liquid cash has come in from up north that its created something of a mini economic bubble, particularly in real estate.

“Several rich Somalis have approached local landlords over the past year to buy dilapidated buildings which they destroy and build apartments to let. They pay in cash and some of it comes from ransoms,” said one local estate agent.

Yusuf Abdi, a 22-year old Kenyan-Somali student, said he has an ex-pirate for a landlord. He charges him around £60 for a single bedroom in a handsome four-storey green and white apartment block in central Kingorani. “Some of the money used to build and develop the building came from piracy, I’m sure of that. [The landlord] is a nice guy though.” Abdi is by no means typical. Many Mombasa residents openly resent the influx of nouveau-riche Somali developers whom they blame for pushing up rents city-wide.

And although most of the cash arrives through hawala – via the agencies which dot central Mombasa – occasionally less conventional methods are used. One journalist I spoke to said money is placed inside defunct electronic equipment imported into Kenya; on one occasion she had seen the back of a TV removed which was stuffed with dollar banknotes.

Abdi’s friend Mohamed, 20, said: “There are no tangible indicators of piracy but suddenly you see there are many Somali businesses, markets and shops here. Since Somalia is a country of lawlessness the [pirate money] comes through unstructured financial systems. It’s an international syndicate and not just in Somalia – the big heads who mastermind it are outside.”

Poor Somalis, often ex-fisherman, constitute the foot soldiers of piracy attacks but their finance and plan of attack hails from elsewhere.

“There is evidence that syndicates based in the Gulf – some in Dubai – play a significant role in the piracy which is taking place off the African coast. There are huge amounts of money involved and this gives the syndicates access to increasingly sophisticated means of moving money as well as access to modern technology in carrying out the hijackings,” said Ledger.

Unsurprisingly, the pirate gangs use information available to the shipping industry to plan their attacks. In addition to having sophisticated equipment to monitor radio traffic, front companies are believed to have signed up to the Lloyd’s List ship movement database and sources such as Jane’s Intelligence to see what protective measures are being employed by their targets.

Back in Battersea the Somali shopkeeper pointed out that hawala long predates piracy, whose root causes were poverty and a lack of central government for the past two decades.

“Hawala will always be here, regardless of the pirates,” he said, pointing out that some of the biggest hawala agencies operate in over forty countries. “People want to send money abroad cheaply, quickly and discreetly – and we’re here to help.”