The best rock you may ever hear – by names you may not know

December 9, 2011An Elegant Writer

December 9, 2011[one_half_last]

The Spy Who Came In From the Seventies

By Eszter Galfalvi

[/one_half_last]

[three_fourth_last]

Director Tomas Alfredson conjures the Cold War era and George Smiley as quintessential Englishman for our time.

[/three_fourth_last]

[three_fourth_last]Translating a book into film is a notoriously difficult task. Viewers will tend to judge the director’s vision against their own inner eye. Nothing–not even reality–can ever compete with a fully-fleshed fantasy created by the imagination. How much more difficult is it then to recreate something which has already been mapped out on screen? And how can a two-hour film compete with a version which has had the scope of a full mini-series to explore the complexities of the written page? The BBC adaptations of Pride and Prejudice and South Riding, for example, undoubtedly owe much of their success to the mini-series format, building a detailed and subtle world into which the viewer can enter, and allowing a clearer articulation of the characters.

The contrast between the new feature version of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and its predecessor, the 1979 BBC mini-series starring Sir Alec Guiness as espionage veterean George Smiley, is striking, largely due to differences in approach. The series is the dramatisation of Le Carré ’s novel, while the film is unmistakably a spy film in its own right. The viewer may therefore be more forgiving if the characters do not exactly correspond to what is called up by the imagination. Nevertheless, any director is undoubtedly taking a risk in carving a new space for this iconic piece.

The contrast between the new feature version of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and its predecessor, the 1979 BBC mini-series starring Sir Alec Guiness as espionage veterean George Smiley, is striking, largely due to differences in approach. The series is the dramatisation of Le Carré ’s novel, while the film is unmistakably a spy film in its own right. The viewer may therefore be more forgiving if the characters do not exactly correspond to what is called up by the imagination. Nevertheless, any director is undoubtedly taking a risk in carving a new space for this iconic piece.

The success of this film is precisely in its ability to transport us to the “old days”. The clues are not ostentatious; everything is naturally in its place. The furnishings and typefaces are all correct, the clothes all in style, and even the small behavioural characteristics are more reminiscent of the men of the seventies. It is visually understated – as opposed to, say, Life on Mars, the strength of which was its self-consciously perfect image of Manchester in the seventies. Our eyes are drawn to the objects as objects, not as symbols of another time—and yet another time is clearly called up before us. Only a few discrepancies can be found, notably in the background of communist Hungary near the start of the film, which depicts an anachronistically multicultural, modern subway scene.

Director, Tomas Alfredson arguably has a more difficult task in conjuring up the Cold War era atmosphere now, so long after the time when Russian spies and the war against communism permeated the cultural vernacular. Somehow, Alfredson must return us to the days when attack from hidden enemies – a more pervasive, insidious threat than the simple brutality of a suicide bomber on a bus – was an immediate concern. We are never allowed to forget the presence of the Russians, even for an instant. Even at the secret service office party. Even as a joke.

Not that we have entirely left behind our Cold War paranoia. Recently, suspected Russian spies were uncovered in the UK and Germany. The truth of the claims regarding these two discoveries is up for debate, but what is interesting about these stories is their exposure so soon after the film’s release. The UK case “exposure” took place in 2010, and yet the case has been dragged into the public eye a year later. Similarly, the agents in Germany have supposedly been retired for some years with little evidence of recent activity. (What happens when a KGB agent retires? An agent never retires, he just joins Lenin for a vodka.)

Regardless of any link – genuine or imagined – between the success of this film and recent events, its effect has been profound, particularly in the UK. The film’s style is undeniably British: understated, cautious, dignified; all characteristics of the television series. But the intervening years have not been kind to the original television masterpiece. Its age is showing, and the style of acting and directing, while outstanding in calibre, are dated in style. Moreover, the DVD version is of a disappointing video quality. This big-screen re-imagining comes at just the right moment, with just the right budget, and with an updated understanding of what it means to be British. The legion of gentlemen, all speaking with received pronunciation in the television series, is no longer accessible to us and a new generation of gentleman must be born. Our main protagonist, George Smiley, exemplifies the heart of the British character as we would like to be seen. He presents us with not only the model of a spy, but the model of an Englishman.

The limited scope of the two hour film shows up a certain lack of detail in some of the other characters, perhaps a necessary sacrifice to give enough time to the main story, but it’s a problem that presents itself rarely. The other suspects at the top of the secret service ladder, aside from Colin Firth, who portrays Bill Haydon with insolent panache, are uniformly unpleasant and occasionally almost interchangeable. Benedict Cumberbatch plays a solid, earnest Peter Guillam, while Mark Strong gives a powerful performance as the disillusioned, broken agent, Jim Prideaux. Gary Oldman’s performance is greatly enhanced by the foil of his supporting actors, and is beautifully nuanced. We are given the occasional nod to his predecessor, particularly at the start, satisfying those who were intitiated by the mini-series, bridging the gap between old and new.

There is a significant build-up to Smiley’s first lines; indeed, he says nothing until a good twenty minutes into the film. This is characteristic of Oldman’s performance throughout: he is so economical in his movements and speech that anything he does or says is of marked importance simply because it exists. A fractional turn of his head blares surprise; a word in the right place carries multiple layers of meaning. His face is at once expressive and enigmatic: a near blank canvas on which the barest hint of emotion registers as clearly as if he had shouted it. His manner carries the distillation of decades of observation, turning him into the perfect vessel – the perfect spy.

There is a significant build-up to Smiley’s first lines; indeed, he says nothing until a good twenty minutes into the film. This is characteristic of Oldman’s performance throughout: he is so economical in his movements and speech that anything he does or says is of marked importance simply because it exists. A fractional turn of his head blares surprise; a word in the right place carries multiple layers of meaning. His face is at once expressive and enigmatic: a near blank canvas on which the barest hint of emotion registers as clearly as if he had shouted it. His manner carries the distillation of decades of observation, turning him into the perfect vessel – the perfect spy.

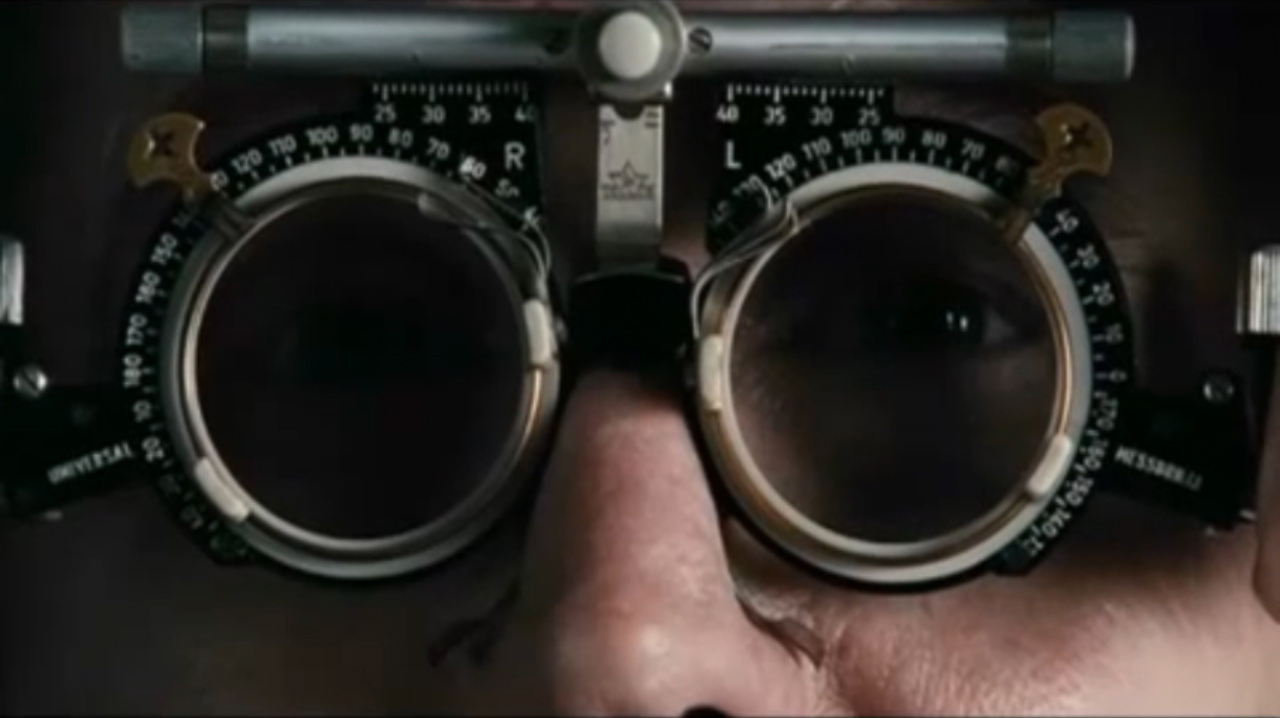

There is a peculiar element of directing in Gary Oldman’s performance. Rather than letting the story speak for itself, the director often works through the actor, subtly but unmistakably moving our attention from object to object through Smiley’s eyes. “What does he see through his large, luminous glasses?” we wonder. We are invited to follow his silent gaze, almost follow his train of thought as he shifts his (and our) focus. Indeed, this technique pervades the film. When Smiley is not present it is the viewer who takes the role of the spy. This illusion is maintained by careful juxtaposition of close-up shots (usually of inanimate objects) and long shots, often through a doorway or from a voyeuristic perspective through a window. In the penultimate shot, Smiley passes from close-up to distant. Out of focus and through a doorway, we now spy on him.

There is much to be appreciated in the cinematography. Visually, the film is beautiful, reminiscent of the bold darknesses of Ridley Scott. A certain reverence is given to the mundane, through close-ups of inanimate objects and small vignettes of everyday actions. Our lives are mundane. We all have eye tests and we all fall asleep while reading in bed. The film presents these small events with a quiet dignity which we would like to think imbues our everyday lives with meaning. Alfredson gives us a bittersweet painting of London, displayed with curiously poetic candour, rather reminiscent of Eliot. A vision of George Smiley, for instance, taking a swim in the Hampstead Ponds on a cloudy day causes a soft nostalgic pang. London is grey and aging, not unlike our protagonist, George Smiley, and we are invited to view her with his jaded but affectionate eye.

A great deal of the effect of this film is built around the perception of the viewer, and much is left for us to infer. More is said in the silences than in speech. This film is full – some might say too full – of pregnant pauses, leaving what would usually be background noises the space to move to the foreground. The clicking of a mint in a silent room, the sound of the wind, and even the dismissive scrape-scrape-scrape of butter on toast all carry carefully coded meanings. Similarly, violence is never gratuitous. In fact, it is omitted until it is most needed. It is brief, brutal, and to the point. The film is full of elisions, of blanks and dropped moments, and yet the continuity remains artfully intact. Even the climax, the crucial moment when the mole in the secret service is revealed to both the characters and to the viewers, surfaces quietly without unnecessary frivolity, to great dramatic effect. It is almost as though the film itself takes the form of a spy. The point is made, and the film calmly removes itself from the scene, leaving only a jumbled impression of itself on the memory.

A great deal of the effect of this film is built around the perception of the viewer, and much is left for us to infer. More is said in the silences than in speech. This film is full – some might say too full – of pregnant pauses, leaving what would usually be background noises the space to move to the foreground. The clicking of a mint in a silent room, the sound of the wind, and even the dismissive scrape-scrape-scrape of butter on toast all carry carefully coded meanings. Similarly, violence is never gratuitous. In fact, it is omitted until it is most needed. It is brief, brutal, and to the point. The film is full of elisions, of blanks and dropped moments, and yet the continuity remains artfully intact. Even the climax, the crucial moment when the mole in the secret service is revealed to both the characters and to the viewers, surfaces quietly without unnecessary frivolity, to great dramatic effect. It is almost as though the film itself takes the form of a spy. The point is made, and the film calmly removes itself from the scene, leaving only a jumbled impression of itself on the memory.

The “good guys” win in the end, but it is a hollow victory. There is something of the Oedipus in any detective story, and this is no different. The end of the line may lead to the discovery of a mole, but nothing is truly won. The end is still tragic. The pervading sense of disconsolation, the grey colour palette, the constant low light and shadows all build in our minds a timeless image of a Britain locked in a futile conflict, where the chess pieces are at a constant stalemate. This film takes us to the Cold War and back, leaving us wistful, confused, and perhaps a little grateful to be living after the thaw of a cold, hard winter.[/three_fourth_last]