Sketching Brazilian Art

February 14, 2012

Tunisia in Spring – One Year On

February 14, 2012By Aldo Ghirardello

He began life as a miller’s son, started out as a stone mason but, through patronage, rose to become an architect and the majority of his work was produced only in a small area around Venice. Yet the influence of Andrea Palladio continues to resonate down the years and throughout the world. Our modern societies’ appearance, in their highest expression, can be traced back to his influence, and he continues to be a source of ever-renewing cultural inspiration.

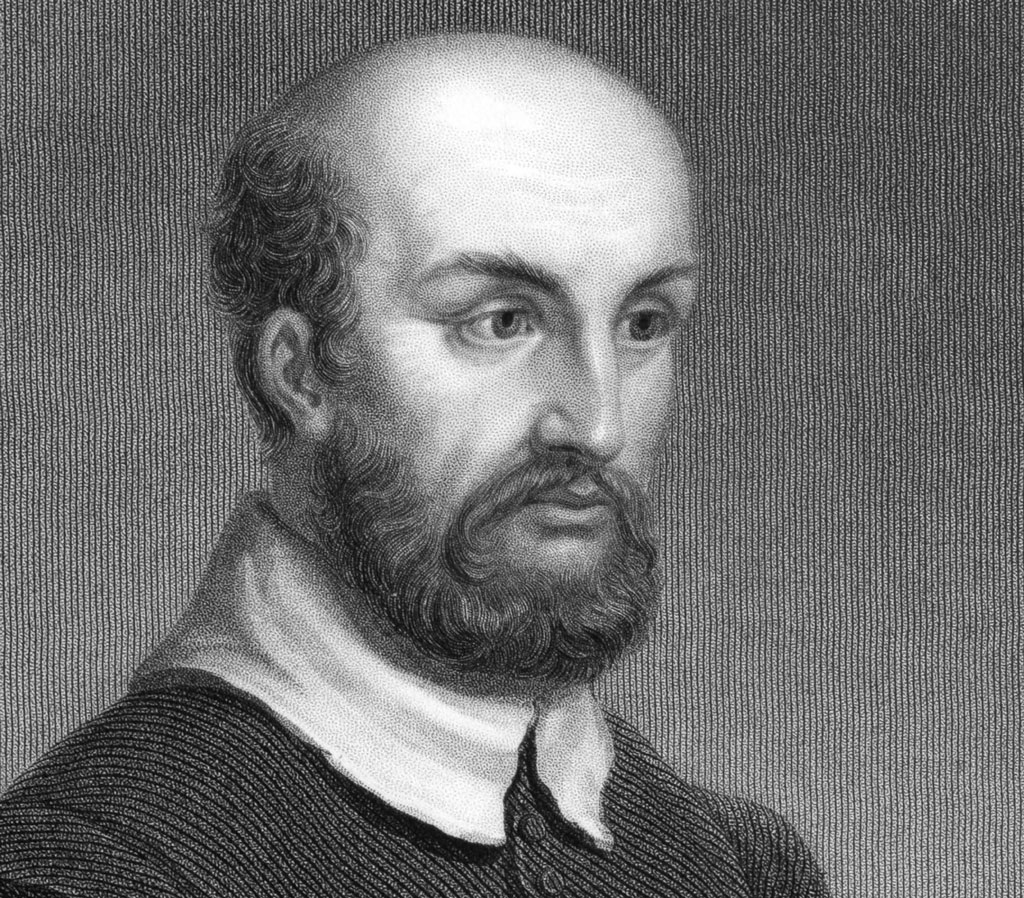

Andrea di Pietro della Gondola (1508-1580), better known as Andrea Palladio, probably would have only been remembered in Padua and its environs as a skilled mason, capable only of designing portals and funeral monuments, had it not been for the pivotal figure in his training, the humanist Gian Giorgio Trissino.

Trissino not only gave Della Gondola the sophisticated name of Palladio, with its strong classical associations, but also introduced him to the cultural atmosphere of Rome in the sixteenth century. This crucial exposure paved the way for Palladio to develop into one of the most – if not the most – influential figure in the whole of Western architecture. He succeeded in bringing to full maturity the original language of Roman architecture.

Trissino was a diplomat for the Papal States and came from a noble family of Vicenza. A poet and dramatist, Trissino was himself interested in architecture, and discovered the young mason at work in his suburban villa at Circoli near Vicenza. He became Della Gondola’s mentor, taking him under his wing and giving him a new name. “Palladio” refers both to Pallas Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom, and to a character in a work written by Trissino himself and literally means “wise one.”

Palladio’s family was of humble origins. His father was a miller. Before he met Trissino in around 1535-38, Palladio began his apprenticeship as a stonemason in Padua, then moved to Vicenza where he was an assistant in the Pedemuro studio, a leading workshop of stonecutters and masons.

His association with Trissino changed his fortunes considerably. His patron was instrumental in getting him trained as an architect, and he continued to support him right until Trissino’s death in 1550. In Rome, Palladio was exposed to the architecture of Bramante, Raphael, and Michelangelo; he studied the classical monuments, copying them by drawing plans and elevations, many of which became part of his seminal treatise “The Four Books of Architecture” published in Venice in 1570. His work adhered to classical Roman principles of architecture which he rediscovered, applied, and explained in his books.

After Trissino’s death, Palladio became associated with another important figure in Italian architecture of the time, the patriarch of Aquileia, Daniele Barbaro, commentator and translator from the Latin of Vitruvius’ “De Architectura”.

Vitruvius was a Roman architect who had dedicated his treatise to his patron, the emperor Caesar Augustus, and the work is one of the most important sources of our knowledge of Roman building design today.

Thanks to Barbaro, Palladio began to work in the field of religious architecture in Venice, and his fame grew to such an extent that in 1570 he was given the prestigious position of Proto, or chief architect of the Serene Republic of Venice, taking over from the great Jacopo Sansovino.

Palladio died in 1580 in rather precarious economic conditions, with several projects unfinished, such as the Rotunda and the Olympic Theatre. However, they were later completed by Vincenzo Scamozzi, one of the leading proponents of Palladio’s unmistakable aesthetic language. He was forty years his junior and had a love-hate relationship with his great master, veering between envy and admiration. Despite these difficulties, however, Scamozzi helped to perpetuate – albeit in less spectacular ways – Palladio’s architectural style.

Although the Palladian language was not the only cultural expression of the power, wealth, and prestige of the Venetian aristocracy in the sixteenth century, it was, however, this style that became the model for English and American architecture in the sixteenth and the seventeenth century.

The relationship between civilization and nature was a major intellectual preoccupation of the sixteenth century. In this cultural debate, Palladio puts forward a theory of perfect harmony and balance between these two entities, incorporating a profound sense of nature, history, and civilization. This may account for the extraordinary success his ideas and work had during the Enlightenment, as his thinking insists on reaffirming how human civilization is in harmony with nature. Many of the now iconic buildings in the newly-born nation of the United States of America – the White House and the Capitol in Washington and Jefferson’s estate at Monticello in Virginia – were Palladian in inspiration. The Redwood Library (1747) and the Marble House in Newport, Rhode Island, the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, and the Woodlawn Plantation in Assumption, Louisiana are other examples.

All this is a successful instance of the brand “Made in Italy”, as we would say today. It is doubtful that the Paduan architect could have ever imagined how far-reaching his influence would extend, crossing five centuries, right up to the present day. On December 6, 2010, by unanimous vote of the US Congress and the House of Representatives and the signing of Concurrent Resolution 259, Palladio was recognized as the “Father” of American architecture by declaring his “Four Books of Architecture” as the most important architectural publication of all time, a model for the architecture of the Western world, and a primary source for American architects from colonial times to the modern era.

So what are the most representative works of this pivotal figure?

He is undoubtedly remembered for those complex structures such as the Basilica of Vicenza and for many city buildings that characterize the historic centres of the main cities in the Venetian hinterland. The world-famous Venetian churches of The Redentore and St. Giorgio have become true icons on the Venice skyline. The superb Teatro Olimpico (Olympic Theatre) of Vicenza, finished after his death, is also another obvious example.

But Palladio’s fame and reputation rest principally on his unique talent for designing villas. These beautiful dwellings, such as Villa Capra, (called La Rotonda), on the outskirts of Venice; the Villa Barbaro at Maser, near Treviso and La Malcontenta in Mira, near Venice, clearly express the ideals and interests of their wealthy owners. On the one hand they serve as places of recreation and rest from the stressful life of the city, and on the other, they function as centres of production for these large estates. There are areas to accommodate the work of the farmhands and storage combined together with delightful places of leisure and entertainment, out of the glare of the summer sun. Palladio’s structures are never ostentatious displays of wealth. but they represent a space of human proportions, functional and balanced, where the joy of life shines through the colours of the frescoes inside – do not forget to visit those by Veronese in the Villa Barbaro at Maser! – while his incorporating of Roman and Greek decorative elements gives them a classical elegance and clarity.

What no doubt caught the attention of the cultural leaders of the young United States was precisely this concept of a dwelling place as an area of both rational and natural experience, a place unencumbered by any religious trappings and free of the tyranny of the city palazzo. They saw in it the most effective expression of freedom as a supreme value, and a model of secularism.

And, indeed, it has proved itself to be well-suited to the needs of changing times.

Although, developed in the sixteenth century, it still finds resonance today, even in such modern masters as Le Corbusier, who was, in fact, an admirer of Palladio and his ideas. And more recently, Palladio still influences the thinking behind the post-modernist style, with its freedom and its much-vaunted timelessness. Palladio’s sixteenth century magnificent structures are embedded in the Venetian countryside. Functional and grandiose at the same time, their underlying design is as clear and bright as the light that floods the interiors. They are models of rationality and civilization, Modern directions, influences, remixes and reworkings in architecture – all bear witness to Palladio as being, even today, the cornerstone and ever-fertile inspiration for building design in the West.