Which Way the Syrian Revolution?

April 30, 2012

The Alchemy of Emma Sergeant

May 26, 2012The idea that business should be responsible for its social and environmental impacts has engendered a lot of resistance over the years. But as with workplace safety and workers’ compensation in the last century, we are gradually coming to a place where doing business with no thought to ecological or human consequences will be, well, unthinkable. Marc Forget explains

A

A short time after the term “corporate social responsibility” (CSR) first emerged in the late 1960s, the concept quickly became the target of scorn and sharp criticism among hard-line free enterprise thinkers. In a 1970 article in The New York Times Magazine, economist and Nobel laureate Milton Friedman referred to CSR as “hypocritical window-dressing.”

Nevertheless, CSR has come a long way since then, and it has evolved into something the originators of the concept probably could not have imagined back in 1970. That is not to say that CSR in its current guise is without its detractors – there are still many. But their criticism is generally specific and highly focused, and few now question the basic idea that business should act responsibly toward the physical and social environments in which it operates.

Despite the fact that the fundamental concept of CSR is seldom disputed, there are wide-ranging and often diverging opinions on the subject. Next to the political and economic ideologies we espouse, the most important factor influencing how we perceive CSR may be the physical, geographical and economic perspective from which we view the corporate world. We will tend to think differently of CSR whether we are a CEO under pressure to reduce current year expenditures or a peasant in a developing country whose land and livelihood are threatened by industrial development or a young outdoor enthusiast concerned about environmental degradation or a stock market investor focused on short-term returns or another investor who analyses long-term risk management in companies.

With such diverse understandings, needs, and ideals among various stakeholders, does the future of CSR lie in “window-dressing” and “greenwashing,” or in bringing about a truly “greener” and more equitable world? A look at the evolution of workplace safety in the 20th century may give us some valuable clues.

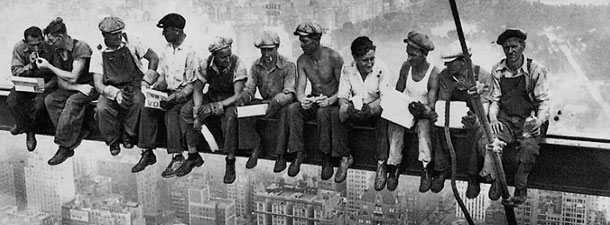

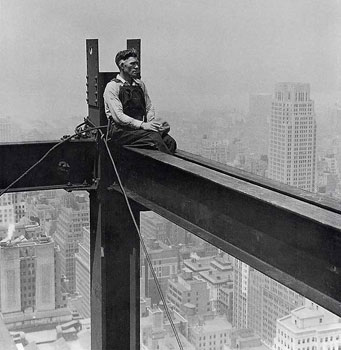

Recently, while looking at photographs of the 1930-31 construction of the Empire State Building, I was struck by the almost complete absence of safety equipment at the site. In Lewis Wickes Hine’s photographs, the construction workers are shown standing on steel beams over 300 metres above street level without any guard rails, safety nets or personal fall arrest systems such as body harnesses and ropes. Items of basic personal protective equipment such as hard hats and goggles are also noticeably absent. The only protective equipment visible in the photos consists of the gloves worn by most workers. At that time the industry estimate for construction fatalities on skyscrapers was one death per floor, although only between 5 and 14 workers died (the number varies depending on the source) during the construction of the 102-floor Empire State Building. That fact seems nothing short of miraculous when looking at Hine’s photographs.

The egregious lack of workplace safety one observes in these historical photos is unimaginable in developed countries today. But in 1930 the safety of construction workers was not the employer’s responsibility. Things have changed much since then. The cost of workplace safety is now as much an integral part of doing business as is the payment of wages. It is unavoidable and no longer even put into question. However, the mainstreaming of workplace safety into modern business practice was slow and difficult. For a long time companies refused to accept any responsibility for the health and safety of their workers, claiming that, as some prominent economists have expressed, business is responsible only to its shareholders, and therefore should solely be focused on increasing its profits.

A number of factors early in the 20th century contributed to eventually making safety the unquestioned business concern it is today in the developed world. Arguably the most important factor was the adoption of workers’ compensation laws beginning late in the 19th century. Following Germany’s lead, other governments in Europe, North America and Australasia passed laws which guaranteed automatic financial compensation for all workplace injuries at a pre-determined and fixed rate. This system was welcomed by business and workers alike. For companies the shared costs were more stable and predictable, while for workers the advantage was greater and more certain benefits. However, it still took many years for companies to become genuinely committed to workplace safety. When they finally did, it was the result of a sharp rise in accident costs (even with workers’ compensation systems in place) and the adoption of legislation that broadened employers’ liability. In other words, business became concerned with safety when it started making economic sense to do so—when implementing measures to reduce workplace accidents and deaths became a better financial proposition than paying the increasingly high compensation costs.

This last fact is very telling, and an important one to keep in mind as we turn our attention back to CSR.

Two very important differences between workplace safety and CSR are worth noting here: workplace safety affects a company’s employees and their families, and legally it is a local issue under the jurisdiction of a provincial, state, or national government where the workplace is situated. CSR, on the other hand, seeks to address issues that affect people who may not have any direct relationship with the company, and focuses on aspects of a company’s activities which, more often than not, take place in many different countries, each with its own distinct and specific laws and regulations. (This last was an important factor in the emergence of CSR, which, not surprisingly, happened at a time when many multinational corporations were formed).

Just as the idea of a government-mandated workers’ compensation system may have been ahead of the curve in 1900, so was the idea of CSR in 1970. Somehow the world has a way of catching up with these maverick ideas, and, as was the case with workplace safety, it may be the increasing cost of not practicing CSR that eventually convinces companies to assume their responsibilities on social and environmental issues.

A few cases that recently made the news underline this point. In June of this year the Peruvian government revoked a decree granting approval to a Canadian company for mining silver at Santa Ana, near lake Titicaca, after a highway linking Peru and Bolivia was shut down for 21 days by protesters, and after some 5,000 protesters descended on Puno, the provincial capital, to demand an end to the mining project. Four months earlier, an Ecuadorian court held Chevron liable for almost $18 billion for oil spills that Texaco (since merged with Chevron) failed to clean up in the 1970s. In June 2010, BP agreed to set up a $20 billion fund for damage claims from its huge Gulf of Mexico oil spill, and suspended dividend payments to its shareholders.

As one would expect, Chevron is appealing the Ecuadorian court’s decision, and the Canadian mining company stated it will sue the Peruvian government. However, successful appeals and lawsuits cannot obliterate the impact of these types of cases. The legal costs alone can be sizeable, and so can damage to reputation. In the end companies still often end up paying huge sums in settlements.

CSR aims to avoid these types of problems by prescribing such practices as the obtainment of free, prior and informed consent from affected populations, and the conducting of full environmental and social impact assessments (the results of which must be disclosed to the public) prior to project development. As the above cases and so many others demonstrate, CSR can and should be an important part of a company’s effective risk management system.

The newsworthy cases may make the economic benefits of CSR obvious, but what has greatly accelerated the adoption of CSR policies and mechanisms in recent years is the fact they are likely to be required for project financing. At present there are 72 financial institutions in 27 countries that have adopted the Equator Principles (EPs), a risk management framework for determining, assessing and managing environmental and social risk in project financing. These 72 institutions currently cover over 70 percent of all international project financing in emerging markets. The EPs are largely based on the International Finance Corporation’s Policy and Performance Standards on Social and Environmental Sustainability (IFC is the private sector arm of the World Bank Group). The IFC Standards and the EPs contain clear requirements for implementation and outcomes, and require clients to fully integrate social and environmental risks management systems into their overall operations and business model. Compliance with the Standards and EPs is assessed regularly, and failure to comply may be considered an event of default and can result in disinvestment by the financial institution.

In the past twelve years a number of other international instruments with goals similar to the EPs and the IFC’s Performance Standards have emerged. They were developed by the UN, multinational corporations, governments, and NGO’s.

Will these efforts reduce environmental destruction and human rights violations resulting from business activities? If workplace safety is any indication, they will. After business embraced workplace safety, the rate of fatal occupational injuries fell dramatically. In both the USA and the EU it has dropped by well over 40% since 1980. These are substantial results, not mere window-dressing, and we should expect the same type of changes following the widespread implementation of CSR practices in business.