Finding the Rhythm of Nature in the Heart of the City

June 9, 2012

The Balancing Act

June 10, 2012Admit it – most of what you know about Nigeria may have come from that email you got offering you big money if you’d just let a Nigerian politician park his millions in your bank account for a while. If so, what Nigel Parsons recounts might surprise you. Nigeria, it seems, has been quietly booming for a while now.

N

Nigeria’s reputation precedes it: rampant violence, endemic corruption, internet fraud, extremes of wealth and poverty, and an HIV crisis out of control are among some of the images that seem to surface when Africa’s most populous nation is talked about. The country definitely has an image problem.

Turn the lens around, however, and look through it from the other way – from Nigeria itself – and this image becomes distorted and out-of-date.

As soon as you step off the airplane at Lagos’ Murtala Mohammed International Airport in Lagos (named after a military ruler assassinated in 1976) the vibrancy of this sprawling city hits you as much as the heat and humidity.

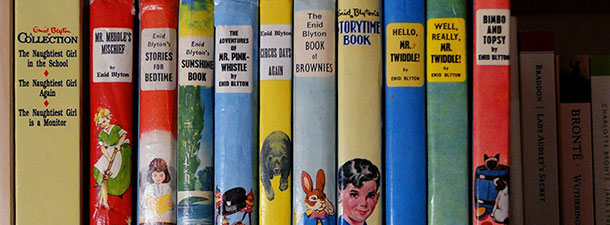

Nollywood Studios

Some of the recent history of the airport itself could almost serve as an analogy for that of the wider city. As recently as 2000, the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration was warning that Lagos airport security did not meet minimum standards. Passengers were subject to harassment by criminal gangs both inside and outside the terminal buildings, and aircraft taxi-ing on the runways were being hijacked and their cargo offloaded.

Then a shoot-to-kill policy was introduced following democratic elections in 1999. The violence dropped, the airport buildings were improved, baggage beltways were repaired, and today it is no better, but no worse, than any number of international airports across the developing world. It feels safe, not threatening, the people relaxed and smiling – even if you wouldn’t be advised to get into a taxi with a driver you don’t know.

Filming in Nollywood

Lagos itself is a vast, sprawling city of around 17 million people, with more arriving every day, drawn like metal filings to the magnet of the Southwest’s booming economy and bright lights.

Just like in any city this size, there are some places you go, and some you don’t, especially at night. Most of us wouldn’t wander around waiting to get mugged in somewhere like unlit tower blocks and the back streets of London. or the gloomy banlieues of Paris, or some of the seedier suburbs of Naples.

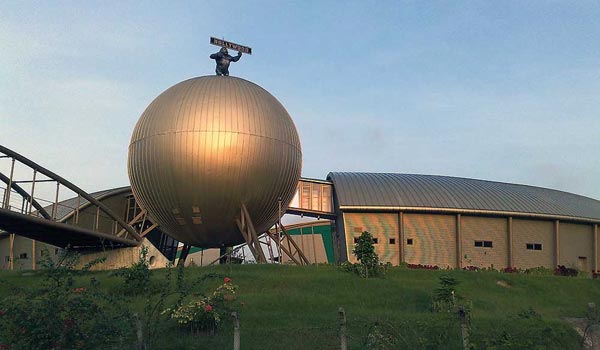

Central Bank of Nigeria

But elsewhere, streets lined with fashionable boutiques thrum to beat of naija, as Nigerians from the acknowledged capital of African hiphop indulge their favourite pastime. In the ex-pat havens of Ikoyi and Victoria Island, young upwardly mobile professionals from Nigeria’s burgeoning middle class relax in trendy cafes and restaurants. On the more recently reclaimed island of Lekki, row upon row of neat, new family homes stand as proof of the prosperity to be had, as orderly children in immaculate uniforms make their way to school.

From here, gazing back at the unelected, banker/French/German-sponsored governments sprouting up along the shores of Southern Europe, Nigeria can look pretty rosy.

While Presidents Merkel and Sarkhozy grapple with bankrupt states, ratings agencies, and re-writing the rules of the EU, Nigeria’s President Goodluck Jonathan, winner of the popular vote last April in elections widely seen as generally fair and violence-free, is living up to his name. He has presided over a period of unprecedented economic growth. Finance Minister Olusegun Aganga has predicted double-digit growth of 12% per annum in early 2012 – outdoing even the new Asian giants of China and India.

Economic reforms over the past decade have put Nigeria’s economy back on track. It now trails only South Africa in the sub-Saharan continent and is poised to take pole position on current performance. Countries like China, India, Turkey, France, Germany and the U.K. are among those falling all over themselves in the rush to get a slice of the action.

Oil drilling in Nigeria

It’s not just the oil – Nigeria accounts for only a little over 3% of world production, pumping out just over 2 million barrels a day. The country also boasts well-developed financial, legal, communications and entertainment sectors. The “Nollywood” movie industry astonishingly churns out more than two thousand films a year in a USD $500-million-a-year business – which means there’s always something new to see in the Lagos cinemas.

More statistics: in the past ten years GDP per capita is estimated to have grown from USD $1,500 per year to something closer to USD $3,500 today, while the number of mobile phone users has risen to 90 million, around 65% of the population.

There’s a mood that things are moving in the right direction. This is reflected in the energetic optimism of the new middle classes – their numbers further boosted by a growing influx of “returnees,” ex-patriot Nigerians from among the world-wide diaspora, coming back to the homeland to take advantage of the business opportunities.

But there are some dark clouds. Half of Nigeria’s estimated 160 million people still live in crushing poverty, while a population explosion means high economic growth rates are going to be needed for some time to come. The United Nations predicts Nigeria’s population to hit around 400 million by 2050.

And while Nigeria has been slowly creeping up the global corruption league table – now ranked only joint 143rd worst on the list out of 182 – most Nigerians betray a weary resignation to corruption continuing in all areas of life, especially public life. Vast energy revenues have simply disappeared, leaving in their wake crumbling roads choked with traffic, vehicles belching out the lowest octane fumes you can find. The road and rail infrastructures simply can’t cope. Fresh water is in short supply, while Lagos suffers daily blackouts, making back-up generators essential household items. At the edge of the city, the power supply just stops. Anti-corruption campaigns and initiatives are a constant theme of government, but no one is holding their breath and expecting the problem to disappear over night.

The pervasive corruption played a major part in the general strike of January of this year, which brought the country to a standstill for a week. Whoever President Jonathan was listening to when he abolished fuel subsidies on January 1, it was the wrong people.

Fuel subsidies exist in Nigeria because only one of the country’s five oil refineries is working – and that one, only partially. So the oil pumped out of the Delta region at huge environmental and human cost (oil companies behave in Nigeria in a manner that would never be tolerated in Europe) is then exported for refining, and re-imported, in the process becoming unaffordable for most people – hence the need for a subsidy. And bear in mind, petrol in Nigeria is not just for your car. It’s also for the generator that is necessary to keep your house lights, television, fridge, etc. working because someone has stolen all the infrastructure money which the oil should have paid for.

On top of that, the country re-imports much more refined fuel than it needs. The (subsidised) excess is then smuggled across the border to Ghana and elsewhere, and sold at a huge profit. More corruption. The removal of the fuel subsidy would have killed this business overnight, but President Jonathan misjudged the rage that an overnight doubling of fuel prices would provoke in his people. It wasn’t just about the money, although the economic knock-on was crippling enough. It was also a venting of the massive public frustration with the way they know they are being cheated, day in, day out.

The strike ended after a week, in a messy compromise that was more a testimony to the fact the most Nigerians wanted to move on, work and improve their lot, than spend their lives on strike. But the root problem has just been temporarily swept under the carpet; it hasn’t been solved. The public anger at the gross unfairness of Nigerian society is still there and will undoubtedly re-surface at some point.

Fishermen in the Ogun River – Lagos

High crime levels also persist, with international drug smuggling and cyber crimes posing particular problems, along with a murder rate that is still significantly higher than that of the United States. It’s with good reason that most visitors remain apprehensive about personal security.

For example, the Lagos newspaper, Punch, reported in November 2011 the case of a shaken British citizen, Khomeini Bhukari, who said he’d been relieved of 200,000 naira (about USD $1,250) and a Breitling watch by two policemen in a park in the capital Abuja after dark. A regular visitor to Nigeria, Mr Bhukari said he’d noted the officers’ names and reported them, but the police found no record of their names on staff rolls. Mr Bhukari declared himself “appalled” at the lack of security, even if you have to wonder what he was doing wandering around after dark with that kind of money, wearing an expensive watch.

But compare that to the Nigerian student, Akinola Olufeni, found dead in South Moscow the same month, his body mutilated and with multiple stab wounds, but his wallet and papers untouched. You also have to wonder about the motive of such a murder in a country plagued by nationalist groups. Russia might have been dubbed “Nigeria with snow,” but this kind of thing is most definitely not a merely Nigerian phenomenon.

Possibly the darkest clouds of all, though, are the activities of the resurgent Islamist group Boko Haram in Nigeria’s hot, poor north. In their boldest attack yet, last August, a suicide car-bomber detonated 150 kg of plastic explosive at U.N. House in the capital, Abuja. Twenty-four people died and 115 were wounded, nearly all Nigerians. In November, a bomb in the city of Damaturu killed at least 67 people. Over Christmas, churches filled with worshippers at the holiest time of the Christian year were bombed with horrific results.

Native Igbo people (overwhelmingly Christian) from the Southeast are fleeing the North en masse again after random Boko Haram attacks on churches, businesses and homes, 45 years after massacres of Igbo communities in the north led to the Biafran war of independence. That war saw an estimated one million people die. Yoruba spokesmen from the Southeast have warned Boko Haram against bringing violence to “Yorubaland,” threatening severe retaliation in the event of any attacks. The spectre of ethnic tensions spilling over into violence is never far from the Nigerian psyche.

The military is working hard to contain an increasingly sophisticated insurgency, but there is little evidence that President Jonathan is doing enough to simultaneously tackle the Islamists’ main grievances of underdevelopment and corruption, meaning there is no end in sight to Boko Haram’s attacks.

The concern is that a full-blown Islamist insurgency could yet derail Africa’s newest economic powerhouse, just as it is getting up steam again and struggling to emerge from poverty and conflict. But if the government can deliver economic reform, especially in the north, as well as military containment, Nigerians will have every reason to stay optimistic that they will remain on course to be not only the continent’s most populous nation, but also its richest.