Mission statement by the editors

July 1, 2012

Working the Trauma Service

July 1, 2012“The life of a modern day troubadour is seldom the luxury and adulation of Rock n Roll stardom. For most hard working Rockers, the road means long hours, short pay, gigs in dirty dives and whatever humble comforts can be had or borrowed. But the true Rocker lives a life apart, one of the last paths open to the modern iconoclast, where the calling is for love of the art and the journey itself, not riches or fame. Long time singer, songwriter and front man Michael Chandler travels in time to rediscover a corner of deepest Americana that left indelible marks on the soul of memory.”

Juke boxes

V

Very seldom was it not a whole lot of fun the night before. After all the driving and waiting around and drinking and weathering the recuperation from the night before that, you finally, like a magician, whip the silk off the bird that had been caged, and some degree of frenzied Hell ensues, no matter how many people are there to take part in it. And it doesn’t end when the show is over. There are always willing participants for the exuberant dance on the precipice which inevitably follows the show. Most of those in attendance at the after-party are not seasoned pros, but were merely caught up in the roiling madness, and who wake the next day, dazed, wondering why they’d done what they did and why they didn’t just start doing it more often.

Cafe by the road

At some point during the morning, we’d return to the nightclub, pick up our gear, and get on our way. It was a time of reflection and preparation, a time to let the human engine idle, as it warms up for another frenetic tear around the track. We’d smoke cigarettes and drink coffee, and I’d have the day’s first beer or two, stashed from the night before, and we’d swap stories loosely or just stab a toe aimlessly into a tree root or a snow bank or the curb. The promoter would show up with an afterglow of astonishment from the mayhem of the night before, usually sporting a loopy grin and, I’m sure, wondering how we could keep up that pace night after night. For us, I guess it was just what we did.

I remember one morning in Morgantown, West Virginia in 1986. The Raunch Hands bumbled up to the bar we had played the night before, where every low-level touring act used to play, where we got a call from our driver, who was still finishing up with the young lady he’d met the night before. He said he’d be there with the van in an hour or so. That was all right. We weren’t in a hurry that morning, and we sure as hell weren’t going anywhere without him and the van. So we could take the time to relax and maybe shoot a couple games of pool over beer and cocktails. The club matron, who had let us in, told us to help ourselves. She was short, stout, and hippie/biker-ish, and she wore a black beret over her long, kinky, saltand- pepper hair. I got a pack of Camels from the machine with the smashed glass and tapped them out as I asked her if there was anyplace around for some coffee and a newspaper. She said she’d come with me. I pointed at the cigarette machine and asked, “We didn’t do that, did we?”

“No,” she said, “It’s been like that for a couple months. I ain’t figured out if I wanna git it fixed.”

We walked out into a bright, young-green, early-May Sunday morning. The club was on a street that ran down a high hill, and she let gravity pull her hefty frame down the sidewalk. She also used her shoulders to bring each leg forward as she walked. I guessed she had bad hips, but she still made pretty good time, and she kept her chin up and took in her surroundings.

I looked down at the top of her beret. “What’s your name again? Is it Carla?”

“Carter. You guys are easy to remember. You’re all named ‘Mike,’ right?” “Three of us. I prefer ‘Michael,’ though.”

“Where y’all been playing, Michael?”

We had been out on the road for about two and a half weeks. I listed off a bunch of the places we had played. She knew of the clubs in Lexington and Louisville, Kentucky, and she said that she had been to the place we had played in Youngstown, Ohio. She told me that, due to what I knew as “club courtesy,” the owner had gotten her “good and drunk” for free. Our band had stayed at the owner, Mike Starr’s, house after that show, and I agreed that he knew how to throw a party. Mike Starr was also rather rotund like Carter.

“You know, I probably could’a went for him, but I saw what he was hangin’ around with, and he likes ‘em younger ‘n me.”

Carter was right. I had seen Mike Starr in action with some of the local coeds. I told her we were on our way to the Jockey Club in Newport, Kentucky, that night, and after two more shows, we were going back home to New York City. I asked her if she had ever been there.

She spat out a giggle and said, “Hell no! Not that I wouldn’t want to, you understand, but I gotta run this bar. When I went up to Youngstown, that was the first time I left Morgantown in three years. No, I got my hands full down here.”

Harley Davidson motorbike

We walked on a bit, and she said, “It gets a body tired. I don’t know how much longer I can keep it up. We do real good money-wise. I just don’t have the energy I used to.” She looked up and locked eyes with me. “It’s definitely a job for somebody younger.”

I said I supposed so, but that she looked like she had plenty more good miles left in her. She navigated us across the street to where a footpath was worn into a grassy vacant lot. It headed down part of the steep hill that had been lazily cut by the Monongahela River, about a quarter mile below us. I lagged back a few paces, as Carter walked ahead of me, and I viewed the green and deep river valley with its bridges and railroad trestles and scores of coal barges in long lines, puffing up-current. I pulled my camera from my jacket pocket and called out to Carter, who stopped and turned around. When she saw the camera, she flashed me a wide, genuine smile, and I got a couple snaps of her with the barges and the green vista. I trotted down a few steps to join her.

Portrait of a biker

“That was sweet,” she said.

“They’ll come out great. You’ve got a terrific smile. I keep a journal on the road, and I like to have pictures to go along with it.” Her eyebrows rose at this new dimension of me. “Well, I’ll be darned. C’mon, the store’s just down here.”

The path made a hairpin turn and dropped to an old brick building on a street corner. The building was from the turn of the century, with tall display windows on the ground floor and apartments above. We went in, and the heavy door tinkled the brass bell above it, signalling our entrance. Everything in the store looked like it hadn’t changed since the 1930s. There were burlap sacks of coffee on the floor; cans of cooked grits and potted meat; a white enamel-and-glass meat cooler with salt pork and slabs of bacon; an old Kodak display with a picture of a girl wearing sunglasses holding a Brownie camera. I asked the balding old man behind the counter for five coffees, “regular.” While he started pouring them from a copper urn, I went and got the local paper (which I loved to do on tour), pulled a couple Dixie beers out of the cooler, and set them on the marble counter. When the man turned around with my coffees, he looked at the beers and then at me. It was a Sunday morning in the South, and if a place sold beer at all on a Sunday, it was usually only after noon that they could.

“He’s alright, Albert. He’s with me,” Carter piped up.

“Is he over eighteen?” Albert wanted to know.

“I’m twenty-five,” I said, and I reached for my wallet to show him my ID. “He did a concert at my bar last night, and he don’t drink like no under-ager. Don’t you worry, Albert, I’ll keep my eye on him,” Carter grinned.

Albert grunted and bagged up my stuff, and I paid him with the few remaining bucks I had. We band members only got paid ten dollars a day, and since our road guy hadn’t shown up yet, I hadn’t gotten my per diem. Carter and I walked outside, where I cracked a beer and lit a Camel.

Bikers

“Y’all don’t make too much money in your band, do you?” Carter asked. I explained we only got ten bucks a day, paid our road guy six hundred a week, hardly ever stayed in hotels, and that we put all the money back into the band for recording, van insurance and maintenance, our manager, booking agent, etc.

“You know, I do pretty well for myself with the bar and all, but like I said, it could sure use someone younger with more energy than I’ve got these days. I was thinking of giving it over to my daughter, but she’s just twenty, and I don’t think she’s ready for all that responsibility just yet.”

Carter sounded as though she was making small talk, but there was something about her tone that felt like she was talking into me. A quick check of Carter’s left hand made me assume that she wasn’t married, so I didn’t ask her what her husband’s role in the bar was, or what he thought of her business decision to move on. I guessed she did it solo. The whole rest of the walk back, she told me all about the club’s workings, the ups and downs, how many people from other places she got to meet, and how it would be “real nice” to have somebody there who knew more about the music that the younger clientele would like. When we got back to the bar, the van had arrived, and a couple of the guys were tinkering under the hood. The rest were enjoying the sunshine. I handed around the coffees and went into the bar to read the paper and maybe have a shot or two of whiskey with my second breakfast beer. As soon as I was inside, Carter came over and introduced me to her daughter Denise who had arrived while we were out. Denise was a very attractive punk-rock girl with a green stripe in her black hair. We talked about life while I had my beer and liberal whiskies. She was smart and engaging and touched my arm a lot to make her various points. I wondered where she’d been last night. We kept up our conversation as I helped hump out the gear.

As we were getting ready to leave, Carter gave me a page torn from a memo pad with her name and phone number on it.

“Why don’t you come down and visit us sometime?” she asked, looking me dead in the eye.

I said I’d try, and Denise put her hands on my shoulders and gave me a soft kiss on the cheek. Indeed, where the hell had she been last night? The guys in the van all gave me inquisitive looks, but I was not going to give them the satisfaction of knowing what I thought – what I was pretty sure – had just transpired back there in Morgantown. If I was not mistaken, a cool, middle-aged woman that I didn’t really know had just offered me a deed to a nightclub and a marriage licence to her intelligent and sexy, brown-eyed daughter. I did my best to process this all the way to the Jockey Club in Newport, Kentucky.

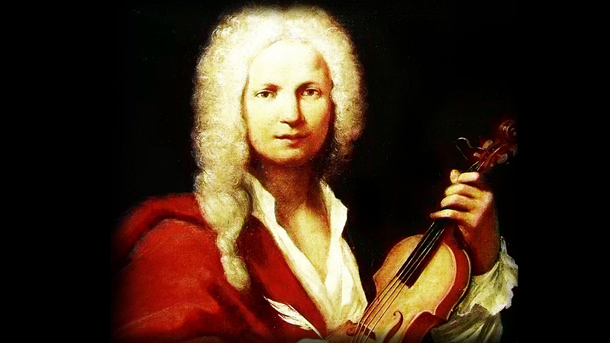

Singer

I liked Newport. It is the harlot sister of Cleveland, Ohio, across the river. It had once been a speakeasy town and a gambling Mecca and was still very seedy. Gambling had remained legal there, and many big stars including Dino, and Frank, and Sammy, and even Marilyn Monroe had played the same stage at the Jockey Club where we were about to perform. The Jockey Club was an old casino that still had horse racing tote boards on its smokestained, walnut-panelled walls. The seedy atmosphere of the town and the faded casino and its motley crowd augmented the Raunch Hands’ ampedup rhythm & blues perfectly. Everything was dim and loud and drunk and sweaty. We received the usual guest appearance by Harmonica Dwayne, a tiny, bald, alcoholic black man in a dinner jacket and tie who was helped onto the stage, where he cupped the microphone and pretended to play harmonica. He was actually really good, and he always bought a round of beers for the band onstage.

That night, for safety reasons, we loaded the gear into the van, along with a couple cases of beer and went to the house where we were going to stay. When we got to their place, they said that they couldn’t fit all of us. There were a few people standing around there, one of whom was a short black girl who weighed about 200 pounds. The guys picked who they wanted to stay with, and nobody wanted to stay with the black girl. I felt really bad for her. She seemed very friendly, and she was offering her home to a bunch of strangers who more than likely would just get very drunk and leave the bathroom a sloshy mess after the morning showers. I said I’d stay at her place.

Her name was Wisteria, after the purple blossom, and she was very bright and gregarious. Her apartment was old and enormous and filled with antique furniture. I asked her about her roommates and was shocked to be told that she had none. I was lamenting leaving all beers with the rest of the band, but Wisteria said that I must be thirsty and brought out a couple cold ones and a bottle of bourbon. She played boogie-woogie on an upright piano while we drank and smoked and sang. We sat on a 1920s chaise lounge and drank bourbon and smoked and talked until it was almost light out.

“Hey,” she asked, “You wanna fool around?” I wondered what that would be like. “Sure,”

I answered. As soon as I got into the van to leave town, there were inquisitive, bemused looks all around, directed straight at me. No one had to ask.

I stuck out my chin, “Yes I did.

” “Ohhhhhh!!” came the howling response, in unison.

“Yes I did, and it was great. And she made me bacon and eggs and grits and homemade buttermilk biscuits for breakfast. She’s a fantastic cook. And she’s an excellent person. And screw you, you don’t get any of the bourbon she gave me for the trip. And where’s my per diem?”

Bourbon on the rocks

I relented on the bourbon, and passed the bottle around, settling into the drive to Pittsburgh, ugh, on a Tuesday. I drifted into a reverie. I had a comfortably full stomach; I’d had a long hot shower, some breakfast bourbon, a full day’s pay yet to spend, another show tonight and one more after that, and then back home to the Greatest City in the World. Through the fabric of my jeans pocket, I idly rumpled the piece of paper with Carter’s phone number on it, which just yesterday had seemed such a tantalising offer. Sure, I’d be going back down there again, but I would be leaving there again for many more days like today.