The Pantheon in Rome: The True Original

July 1, 2012

Santiago’s screaming streets

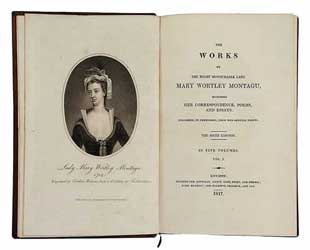

July 1, 2012Those are the supposed dying words of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, whom one biographer described as being “the best platonic female company that Eighteenth Century England can provide. …She moved about from place to place. …She met everybody; she heard, or overheard, everything; she moralised; she satirised; she ridiculed; she devoured all the good books of her day and most of the trash. …She wrote better, she saw more, she knew more, she had certainly more vivacity and spirit,” than almost any other chronicler of London social life of the day.

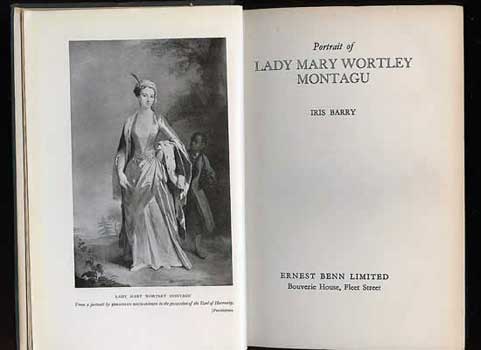

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu with her son

A

A common refrain among the hundreds of women travel writers who emerged in the 18th and 19th centuries was their indebtedness to Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689-1762), an eccentric English aristocrat who was a child prodigy, a star at the Hanoverian court, the quintessential “intrepid” traveller, a proto-feminist and much more besides. In her lifetime she published poetry, satire, and even the first piece by a woman in the Spectator but, curiously, never a travel book.

Instead, at home or away, she poured out letters to family and friends about whatever she was up to – and that was always a lot. She began travelling in her late twenties when, in the company of her husband and infant son, she ventured overland across Europe to Constantinople, capital of the Ottoman empire. There her husband, Edward Wortley Montagu, was to take up his appointment as the new British ambassador.

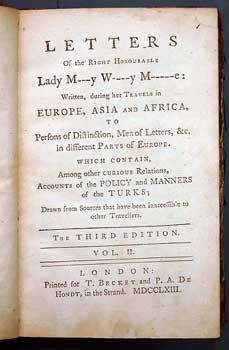

Book Lady Mary Wortley Montagu – Letters |

Book Lady Mary Wortley Montagu – Letters |

Their journey coincided with the outbreak of war between the adjacent Habsburg and Ottoman empires, so crossing the battle zone between them was bound to be dangerous. She took this in her stride: it would improve her letters. Those to her “dear sister,” the Countess of Mar, were generally a summary of what had happened since her previous letter. On the other hand, those to “Mr Pope” (i.e. Alexander Pope), for example, included digressions into common interests – in his case, poetry. Lady Mary took for granted that all her correspondents were interested in the sexual peculiarities she encountered, especially those that highlighted differences between the Christian and Muslim worlds.Her sister was the first to learn of “one of the pleasantest adventures I ever met in my life. It will give you a just idea of the delicate manner in which belles passions are managed in this country.” She was in Vienna, the Habsburg capital.

“The young Count of —-, leading me downstairs, asked me how long I was to stay at Vienna; I made answer that my stay depended on the emperor,and it was not in my power to determine it. Well, madam, said he, whether your time here is to be longer or shorter, I think you ought to pass it agreeably, and to that end you must engage in a little affair of the heart.”

My heart, answered I gravely, does not engage very easily, and I have no design of parting with it. I see, madam, said he sighing, by the ill nature of that answer, I am not to hope for it, which is a great mortification to me that am charmed with you. But, however, I am still devoted to your service; and since I am not worthy of entertaining you myself, do me the honour of letting me know whom you like best amongst us, and I’ll engage to manage the affair entirely to your satisfaction.

“Thus you see, my dear,” she concluded to her sister, “that gallantry and good-breeding are as different, in different climates, as morality and religion.Who have the rightest notions of both, we shall never know till the day of judgment, for which great day of eclaircissement I own there is very little impatience in your, etc. etc.”

She made copies of all her letters in case they were lost in the post, or perhaps thrown into a fire, and at the same time kept a voluminous private diary that kept all her adventures and secrets in one place. She considered writing an autobiography that incorporated all these elements but decided against it. Her daughter paged through the diary after Lady Mary’s death and then – as a matter of “filial piety,” according to Isobel Grundy, Lady Mary’s most comprehensive biographer – destroyed it.

Book Lady Mary Wortley Montagu |

Book – Lady Mary Wortley Montagu |

Nevertheless, enough copies of her letters survived to provide the material needed for “Turkish Letters”, a pirate account of her journey to Constantinople. Its publication caused a sensation; so much so that a legitimate version soon followed with the addition of some of Lady Mary’s poetry. Dr. Johnson pronounced it the only book he could read with pleasure from beginning to end. With subtle variations of title, it is still in print some 250 years later.Mary was the first child of Evelyn Pierrepont and Lady Mary Fielding, a cousin of the novelist Henry Fielding, author of Tom Jones (which Dr. Johnson had condemned as “vicious”). Mary’s mother died when she was three, so she was brought up by her paternal grandmother until she was old enough to join her father at Thoresby Hall, in Sherwood Forest, Nottinghamshire. She had by then become Lady Mary on her father’s succession to the earldom of Kingston.Thoresby Hall had one of the finest private libraries in England, “fitted out in black leather and morocco with busts of classical philosophers.” It became her refuge from an appalling governess, “the worst in the world,” and was the means to her “stolen” self-education. She secretly learned Latin for access to books that accelerated her progress.

By age 14, Lady Mary had written a fair amount of poetry, a novel, and a romance along the lines of Aphra Behn, one of the earliest English novelists and a champion of “noble savagery.” Lady Mary also established a literary circle for girls her age and was engaged in earnest correspondence with two Anglican bishops.

Edward Wortley Montagu, a brother of one of the girls in the literary circle and a grandson of the first earl of Sandwich, fell in love with her and used his sister as the courier for his letters to her. The sister died when Lady Mary was almost 21, whereupon Edward broke cover and asked for her father to recognise him formally as her suitor. In an age when marriage was above all a financial transaction, Edward was turned down because he refused to commit his fortune to a hypothetical first-born son. On the other hand, Clotworthy Skeffington, an Irish aristocrat whose given name, it transpired, was entirely appropriate, had no such reservations and was declared the official suitor.After two years of insisting that Edward was her preference, Lady Mary announced that she wished to marry an unidentified third party. The newcomer’s name was kept under wraps pending enquiries into his financial status. Anticipating the verdict, Lady Mary had visions of being coerced into nuptials with Clotworthy and therefore chose to elope there and then with Edward. They married in Salisbury in August 1712, and nine months later had a son, another Edward. To crown their first wedding anniversary, Lady Mary’s article appeared in the Spectator and Edward assumed a seat in parliament as the member for Westminster.

On the accession of George I in 1714, the couple were rising stars at court when calamity struck. Lady Mary was brought down by smallpox and looked certain to die. Pustules covered her whole body, her eyebrows fell out, and her face swelled to a size that made her unrecognisable. Recover she did, however, only to learn that in the interim she had been banished from court.

Edmund Curll, a notorious Fleet Street publisher, had produced an anthology of “anonymous” satirical pieces. The preface, however, named Alexander Pope as one of the contributors, and it soon emerged that a “lady of quality” accused of defaming the princess of Wales was Lady Mary. It seems it did not matter that the tirade against the princess was delivered by a satirical character who was a palpable lunatic, a format exemplified by Jonathon Swift’s proposal that “Irish children would be a lesser burden on their families and country if they were eaten”.As things turned out, the furore evaporated with the news that Edward Wortley Montagu would be leaving the country to take up his appointment in Constantinople as the new British ambassador to the Ottoman Porte, and his wife and baby were going with him.

Lady Mary’s first letter from abroad was to her sister, the Countess of Mar. Posted from Rotterdam on 3 August 1716 after a stormy Channel crossing, it was a mark of her single-minded determination. “I never saw a man more frightened than the captain. For my part, I have been so lucky, neither to suffer from fear nor sea-sickness.” Their arrival, however, coincided with the Battle of Petrovaradin in Serbia, in which outnumbered Habsburg forces defeated the Ottoman opposition.

Edward had business to attend to in Vienna, but the route to Constantinople from there meant running the gauntlet of marauding deserters and picking a way through rotting corpses, horses and camels. Lady Mary told Alexander Pope she expected the worst:

“I think I ought to bid adieu to my friends with the same solemnity as if I was going to mount a breach, at least, if I am to believe the information of the people here, who denounce all sorts of terrors to me; and indeed, the weather is at present such as very few ever set out in. I am threatened, at the same time, with being frozen to death, buried in the snow, and taken by the Tartars, who ravage that part of Hungary I am to pass. ‘Tis true we shall have a considerable escort, so that, possibly, I may be diverted with a new scene, by finding myself in the midst of a battle. How my adventures will conclude, I leave it entirely to Providence.”

In the event, they crossed safely into Ottoman territory near Belgrade, but then had to wait for permission to continue. They were lodged in “one of the best houses, belonging to a very considerable man amongst them and have a whole chamber of Janissaries [elite Christian troops in the Ottoman army] to guard us. My only diversion is the conversation of our host Achmet-beg, a title something like that of count in Germany. His father was a great pasha, and he has been educated in the most polite easternlearning, being perfectly skilled in the Arabick and Persian languages, and an extraordinary scribe, which they call effendi.”

Her host told her that he preferred an easy, quiet life rather than dangers inherent in holding high office in the Porte. “He sups with us every night, and drinks wine very freely.” He introduced her to Arabian poetry and “expressions of love that were very passionate and lively.” They had frequent disputes, too, mainly about the confinement of women. “He assures me that there is nothing at all in it; only, says we [i.e. Muslims] have the advantage that when our wives cheat us, nobody knows it.”

Lady Mary felt that conversation with the effendi gave her a better understanding of the Muslim religion than any Christian before her. She tried explaining to him the difference between the religions of England and Rome, “and he was pleased to learn there were Christians that did not worship images, or adore the Virgin Mary. The ridicule of transubstantiation appeared very strong to him.”

Asked about his consumption of alcohol, he replied that “all the creations of God are good and designed for the use of man.” Nevertheless, the prohibition of wine “was a very wise maxim, and meant for the common people, wine being the source of all disorders among them. But the prophet never designed to confine those that knew how to use it with moderation; nevertheless, [the effendi] said that scandal ought to be avoided, and that he never drank it in publick.”

As the journey progressed, she attempted a reconciliation with the Princess of Wales. “I have now, madam, finished a journey that has not been undertaken by any Christian, since the time of the Greek emperors; and I shall not regret all the fatigues I have suffered in it, if it gives me an opportunity of amusing your R.H. with an account of places utterly unknown amongst us.” The inhabitants of Serbia, she told the princess, were hard-working “but the oppression of the peasants is so great, they are forced to abandon their houses, and neglect their tillage, all they have being a prey to the janissaries, whenever they please to seize upon it. We had a guard of five hundred of them, and I was almost in tears every day, to see their conduct in the poor villages through which we passed…”

The country from hence to Adrianople is the finest in the world. Vines grow wild on all the hills, and the perpetual spring they enjoy makes everything gay and flourishing. But this climate, happy as it seems, can never be preferred to England, with all its frosts and snows, while we are blessed with an easy government, under a king who makes his own happiness consist in the liberty of his people, and chooses rather to be looked upon as their father than their master.”

A letter written, or more likely posted, on the same day, 1 April 1717, was to “The Lady—-“, who had previously complained of being excluded from Lady Mary’s juicier anecdotes. “I write to your ladyship with some content of mind, hoping, at least, that you will find the charm of novelty in my letters, and no longer reproach me that I tell you nothing extraordinary. “I won’t trouble you with a relation of our tedious journey, but I must not omit what I saw remarkable at Sophia [Sofia], one of the most beautiful towns in the Turkish empire, and famous for its hot baths, that are resorted to both for diversion and health.” What followed was probably the bestknown episode in the Turkish Letters, completely excluded from the letter posted to the princess of Wales on the same day.

Book Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

Lady Mary hired a curtained Turkish coach so that she could travel incognito to a particular bathhouse. At 10 a.m. it was already full. The circumference of one of five domed buildings was lined with two tiers of marble “sofas” covered with cushions and rich carpets. The lower tier was for the ladies, the upper for their slaves, “but without any distinction of rank by the dress, all being in the state of nature, that is in plain English, stark naked, without any beauty or defect concealed.”

Book – Letters from the Right Honourable Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

Yet there was not the least wanton smile or immodest gesture among them. They walked and moved with the same majestick grace…. There were many amongst them, as exactly proportioned as ever any goddess was drawn by the pencil of a Guido or Titian – and most of their skins shiningly white, only adorned by their beautiful hair, divided into many tresses, hanging on their shoulders, braided either with pearl or ribbon, perfectly representing the figures of the graces….”

Streams of water cascading across the floor in little channels became so hot “[that] ’twas impossible to stay there with one’s clothes on.” She would happily have removed her riding dress but it was held in place by stays. “I was here convinced of the truth of a reflection I have often made, that, if it were the fashion to go naked, the face would hardly be observed. I perceived that the ladies of the most delicate skins and finest shapes had the greatest share of my admiration, though their faces were sometimes less beautiful than those of their companions. To tell you the truth, I had wickedness enough to wish secretly that Mr. Jervas [Charles Jervas, who had painted her portrait] could have been there invisible.”

Portrait – Lady Mary Wortley Montagu |

Book – The works of Honourable Lady Mary Wortley Montagu |

I fancy it would have very much improved his art, to see so many fine women naked in different postures, some in conversation, some working, others drinking coffee or sherbet, and many negligently lying on their cushions, while their slaves (generally pretty girls of seventeen or eighteen) were employed in braiding their hair in several pretty fancies. In short, ’tis in the woman’s coffee-house where all the news of the town is told, scandal invented, etc.”

They generally take this diversion once a week, and stay there at least four or five hours, without getting cold by immediately coming out of the hotbath into the cold room, which was very surprising to me. The lady that seemed the most considerable among them, entreated me to sit by her, and would fain have undressed me for the bath. I excused myself with some difficulty. They being, however, all so earnest in persuading me, I was at last forced to open my shirt, and show them my stays, which satisfied them very well; for I saw they believed I was locked up in that machine, and that it was not in my own power to open it, which contrivance they attributed to my husband.”

I was charmed with their civility and beauty, and should have been very glad to pass more time with them; but Mr. W [her husband] – resolving to pursue his journey next morning early – I was in haste to see the ruins of Justinian’s church.”

In retrospect, she added, she had seen no reason to believe rumours of rampant unnatural liaisons among women in the bathhouse, but that did not mean Turkish ladies committed “one sin fewer” than their Christian counterparts. “Perpetual masquerade [i.e. the veil] gives them entire liberty of following their inclinations without danger of discovery. The usual method of intrigue is to send an appointment to the lover to meet the lady at a Jew’s shop, which are notoriously convenient. …The great ladies seldom let their gallants know who they are.”

Lady Mary adopted a more serious tone in describing a discovery which, given her recent medical history, amounted to a miracle. Remarkably, the letter to “Mrs. S.C.” was posted on the same day as the account of the visit to the bathhouse but was without any reference to that. “There is a set of old women, who make it their business to perform an operation, every autumn, in the month of September, when the great heat is abated.”

The operation was called “ingrafting,” and it was performed on parties of fifteen or so. “An old woman comes with a nut-shell full of the matter of the best sort of small-pox, and asks what vein you please to have opened. She immediately rips open that you offer to her, with a large needle (which gives you no more pain than a common scratch), and puts into the vein as much matter as can lie upon the head of her needle, and after that, binds up the little wound with a hollow bit of shell, and in this manner four or five veins… The children or young patients play together all the rest of the day, and are in perfect health to the eighth. Then the fever begins to seize them, and they keep their beds two days, very seldom three… and in eight days time they are as well as before their illness.”

She consulted Charles Maitland, the surgeon at the British embassy, about the practice and, with his support, first had her young son and then a baby daughter inoculated, both without ill-effect. A raging smallpox epidemic in 1721, after her return to England, saw Lady Mary campaigning for the introduction of inoculation, and in this she was joined by Caroline, Princess of Wales. The latter persuaded a group of prisoners awaiting execution in Newgate gaol to offer themselves as guinea pigs. The trial worked perfectly: the condemned men survived and walked out of prison as free men.Nevertheless, her life back in England did not run smoothly. The “dear sister” of her letters, Lady Mar, went mad. She fell out with Pope. Her son was an uncontrollable hooligan and her marriage cooled. In 1736, the year of her daughter’s wedding to Lord Bute, Lady Mary fell in unrequited love with a young Italian, Count Algarotti, and pursued him across Europe by letter. Eventually she moved to Italy, first to Venice and then to Avignon and Brescia, where she was almost bed-ridden for a decade. Worse still, she rented a house from the Palazzi family, who were upper-class gangsters. The letters to her daughter continued, but they lacked the sparkle of their now distant predecessors.

Planning a return to England in 1761, she deposited the manuscript of her Embassy Letters with Benjamin Sowden, a clergyman in Rotterdam. It was eventually passed on to Lord Bute, her son-in-law, but not before being copied illicitly by two men working for London publishers. She was given a royal reception on her return to London but her health was then failing rapidly and she died on 21 August 1762.