Mexico’s Eco-tourism Quest: In Search of a Gentle Shark

September 10, 2012

Malina Pasthira: Sustainable Architecture in Thailand

September 10, 2012

Mark Beech

Rock music can be less cerebral than other arts, a little less caring. In its purest form, it often appeals more to parts of the body below the waist than to those above the collar. But that doesn’t mean it can’t have an impact – and a significant one – in the struggle to save the planet.

I

If you believe the most pessimistic timescale, we have a few short years, maybe even mere months to save our planet from destruction. The urgency and magnitude of this task is overwhelming.

The world’s future has long exercised novelists, poets, painters, actors and sculptors. So what happens when such an agenda meets music? Rock, pop, dance, rap and soul together make up what is arguably the most potent, pervasive and persuasive form of popular culture. It has potentially the greatest power to change hearts and minds.

Neil Young, poses with his guitar

during the making of the album

“Le Noise.”

That could be an invaluable weapon for green campaigners – though on the face of it, such an affinity might not be obvious. Commercial music is a natural partner to fashion, art and film. It sits less comfortably with political rhetoric and campaigning. Much modern music is synonymous with a sense of revolution, a whiff of danger and a view that world issues are just a bit too serious.

Popular music is rarely elitist, white collar, upper class and right wing. It’s usually all-encompassing, blue collar, working class and liberal, if not left wing. It has long spoken to youth concerns, and not just the right to party (apologies to the Beastie Boys), to play loud music and stay out late.

|

|

Pop has often also been about “sticking up for the little guy”, and sticking it to “The Man.”This anti-capitalism has frequently sat oddly next to the record companies’ aim of making as much money as possible, but that is the fundamental contradiction at the heart of rock. As Elvis Costello noted on “The Other Side of Summer”: “Was it a millionaire who said ‘imagine no possessions’?”Yes, he was referring to John Lennon – ironically, one of the most political of rockers.

And there’s always been a breed of rocker who burns fuel and cash with ostentatious methods of transport – rides that pump noxious greenhouse gases. Consider how much damage was done by Elvis Presley’s gas-guzzling Cadillacs in the 1950s, Lennon’s Rolls-Royce Phantom Vs in the 1960s (he owned two of them), and Rod Stewart’s Lamborghini Muira in the 1970s. Or we might gulp at the private helicopters or jets favoured by Jamiroquai, Elton John, Pink Floyd, the Eagles or Led Zeppelin.

|

|

In July 1985, Phil Collins was actually applauded for supersonically jetting across the Atlantic during the Live Aid charity concert. He sang “Against All Odds”and “In the Air Tonight”in London before literally taking to the air himself, dashing to Heathrow for a Concorde flight to New York, then on to Philadelphia. There were frenzied helicopter hops between the venues and airports. How we marvelled as he sang for a second time, casually remarking “I was in England this afternoon… funny old world, innit?”

Few people questioned whether this was a good use of resources. In 1985 the term “carbon footprint”wasn’t part of common parlance. And after all, the airliner, on its normal run, would have burned the same amount of fuel whether Collins was on board or not. He did it to promote the plane, Britain, the concert – and just because he could. Hell, he’s a rock star, we all said. If you’ve got it, flaunt it. And to be fair, practically no one at the time connected such climate-deranging practices with phenomena like the very drought-induced famine the concert itself was meant to alleviate.

|

|

Still pop music has demonstrated, from its earliest days, some political tinges within certain areas of concern – class being, as I mentioned, one of those areas. And in the 1960s, those tinges became more and more prominent.

One of the key records of that era, and indeed of any era, was Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On”from 1971. I replayed the LP recently for the first time in ages. I’d forgotten quite how good it is.

|

|

The song cycle is full of feelings for the world, most obviously on “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)”which became a single after an insistent Gaye convinced Motown to release it. The company had serious misgivings about his move away from the straightforward love songs he used to write for his singing partner Tammi Terrell, who had died in 1970. But he got his way, as one of Tamla’s biggest stars, and the rest is history.

It’s the singer’s masterpiece and it was remarkably daring for its day. Indictments of poverty and pollution go down more easily when they are wrapped round by seductive Bob Marley reggae or silky R&B – check out Gaye’s “Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler).”

|

|

At much the same time, Joni Mitchell wrote “Big Yellow Taxi,”inspired by the depressing view of a concrete field from her Hawaii hotel window, with the beautiful mountain skyline in the distance, showing how it used to look.

“They paved paradise and put up a parking lot,”she famously opens. The lines “they took all the trees, and put ‘em in a tree museum”refer to a Honolulu garden of endangered plants. Mitchell also encompasses organic food with “hey farmer, farmer, put away that DDT now.”On some concert versions, Mitchell adds an extra environmentally-friendly verse, suggested by Bob Dylan’s 1973 cover of the song, with a big yellow tractor talking away her house and land.

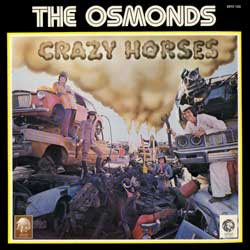

Neil Young & Crazy Horse

Mitchell’s friend Neil Young also writes with genuine passion about environmental degradation. In fact, he seems to be getting angrier as time runs out, forests are torn down, and oil reserves get drained dry. Earlier Young compositions such as “After the Gold Rush,”with its vague post-apocalyptic vision, evolved into more explicit material such as “Vampire Blues,””Natural Anthem,”and the snarling “Piece of Crap.”The “Greendale”project in 2003 spanned a CD, book and movie calling for an end to smoking chimneys and dangerous power. “Rockin’ in the Free World”rails at “Styrofoam boxes for the ozone layer – fuel to burn and roads to drive”.

Young’s “Fork in the Road”album was inspired by his 1959 Lincoln Continental being converted to run on alternative energy – the so-called Lincvolt project. Young sank $120,000 of his own money into the classic car which supposedly achieved gas mileage of 100 miles to the gallon. The project even survived a fire when the Lincoln was left plugged into an electrical socket which wasn’t properly tested.

Young isn’t the only star to take green initiatives away from what you hear on the record. Bands still need to do world tours, of course, and that by definition involves a lot of travel. Radiohead made a huge fuss with what it claimed was the first carbon-neutral concert series. Pearl Jam also “tours green”and works with conversation organisations such as EarthCorps.

Alanis Moirssette

There’s a Green Music Group which includes Alanis Morissette, who runs her tour buses on biodiesel and uses solar panels. Coldplay, Dave Matthews Band, Willie Nelson, Bonnie Rait, Linkin Park and Janelle Monáe support another non-profit organisation, Reverb.

Such efforts pale into insignificance, though, when put next to the efforts of U2. Let me run this sentence past you:

“One of the world’s biggest rock stars, Bono, is being increasingly talked of as one of the most powerful politicians and environmental campaigners too.”

Okay, that’s a test designed to produce an emotional response. Bono has spanly divided people.

On the minus side, a rocker can appear faintly ridiculous when he plays at being a statesman. Bono has been called a pretentious, smug meddler. His detractors argue that rather than being a serious rebel, he is a court jester, playing into the hands of the professionals.

Bono stands repeatedly accused of becoming too big for his own high-heeled boots, spouting off on subjects he knows little about, and doing it all for his own self-aggrandisement. According to his enemies, this may be to satisfy ego, ease guilt at making millions, get free column-inches, promote records and give himself something interesting to say.

On the plus side, Bono’s supporters paint him as a saint and a modern-day superhero who is prepared to risk damaging U2’s credibility for the cause. The Edge has raised concern about his friend dining with right-wing politicians and businessmen. Bono responds: “I’d have lunch with Satan if there was so much at stake.”

Bono’s campaigns for world poverty and ecological management have put him on first-name terms with world leaders, though you’d virtually need to live on another planet not to have heard of him. While he’s been nominated several times for the Nobel Peace Prize, that’s not a difficult feat – literally hundreds of folks are put forward for the prize. It’s more impressive that he has been a frontrunner in online betting before each announcement.

Bono has done his homework, lobbyists say, and has spent years globetrotting, making speeches to the UN, World Economic Forum, IMF and G7. He has raised more than $1 billion for world poverty through lobbying the U.S. government alone, according to some reports. Other newspapers claim that the Bono-backed African Well Fund has saved more than 5,000 lives in Mali, Angola and elsewhere by addressing water-shortage problems. Drilling clean wells provides healthy water, cuts down disease and provides proper irrigation for crops.

That doesn’t make him immune from criticism but it should give pause to those who condemn him: how many lives have they saved? Five thousand?

The UN’s special adviser on poverty, Jeffrey Sachs, said in Dublin in an address to members of the Institute of European Affairs that if Bono wasn’t the most important politician in the world, he was “definitely number two.”

In 1992, U2 also joined a protest at a U.K. nuclear processing plant at Sellafield and joined a “Stop Sellafield”concert. The organiser Greenpeace has repeatedly questioned the plant’s safety record and says that it has the highest concentration of radioactivity on the planet with consequent risks to the lives and health of those living nearby.

Such nuclear concerns have been going for decades in music. The Musicians United for Safe Energy (Muse) movement founded by Raitt and others in 1979 also produced the “No Nukes”concert and video with Bruce Springsteen, Jackson Browne and others.

Just about all the major environmental concerns have come up somewhere, from the rise of polluted seas (“London is drowning and I live by the river,”sang the Clash) to the destruction of the Brazilian rainforests – a subject dear to the heart of Sting, whose tracks include “Fragile Planet”.

Music has made people think about the environment, as well as war, power, money, nuclear energy, feminism, sexual and racial discrimination.

Even if it hasn’t changed opinions single-handed, it’s reinforced other calls for action.

It has saved thousands of lives and raised millions of dollars via Live Aid, Band Aid, and U.S.A. for Africa – even if it hasn’t eradicated the root cause of starvation and pollution.

It has encouraged people to join and donate to organisations such as Greenpeace and Amnesty International.

Sting – Euro tour recording;

Royal Philharmonic Concert Orchestra

Bob Geldof, Michael Stipe, Peter Gabriel and Sting know they can have an effect – or there’d be little point in trying. It takes chutzpah and self-confidence to put your head over the parapet.

And we can enjoy many classic songs about our imperilled planet. And not necessarily all in English. Greek-born Eurovision winner Vicky Leandros sung “Verlorenes Paradis”(“Forlorn Paradise”) in 1982, saying we are poisoning our rivers, fish and forests. Argentina’s Los Piojos made an even more stark warning with the 2007 CD “Civilisación.”

Sure, there have been some simplistic rants. There are also artists who understand the complexities. As Frank Zappa says in the introduction to “Joe’s Garage,””environmental laws were not passed to protect our air and water, they were passed to get votes.”

The Beach Boys

Courtesy of Brian Wilson Archive

There have also been some of the greatest pieces of music, which are worth hearing.

A short list follows (in no particular order):

Joni Mitchell – “Big Yellow Taxi”

One of the first environmental rants, released in 1970, which moves off into personal concerns as Joni’s boyfriend departs in a taxicab.

The Doors – “Ship of Fools”

Jim Morrison gets all pessimistic on this 1970 track, telling us “smog will get you pretty soon.”It’s not the only song to mention Los Angles fog: the Beatles did it in “Blue Jay Way.”

The Beach Boys – “Don’t Go Near the Water”

The lead-off track on 1971’s “Surf’s Up”puts a green spin on the Boys’ usual surf, sea and sun agenda.

Marvin Gaye – “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)”

Gaye’s 1971 lament says blue skies have been replaced by smog, the wind is poisoned and oceans are sullied with oil and radioactivity.

Midnight Oil – “Beds are Burning”

The 1987 single by Australia’s Midnight Oil advocates giving desert land back to native people and notes: “How can we dance when our earth is turning/ How do we sleep while our beds are burning?”About two decades later, vocalist Peter Garrett became Australia’s environment minister.

Neil Young – “Mother Earth (Natural Anthem)”

The guitar-feedback live climax to the 1990 “Ragged Glory”studio LP ends with the members of Crazy Horse intoning “Respect Mother Earth and her giving ways, or trade away our children’s days.”

Jack Johnson – 3 R’s

“Reduce, Reuse, Recycle,”goes the chorus of this 2006 ditty written for the film “Curious George.”The Hawaii surfer and folk singer also helped the clean-up after the Gulf of Mexico oil spill.

Gorillaz – “Plastic Beach.”

The excellent 2010 concept album has the band’s characters getting washed up on a beach covered in non-biodegradable plastic bottles.

Honourable mentions to

Jimmy Cliff – “Save Our Planet Earth,”

Melissa Etheridge – “Wake Up,”

Crosby, Stills & Nash, “Clear Blue Skies.”

[note]

More information: mark@markbeech.net;

www.bloomberg.com/muse/mark-beech/ or @Mark_Beech

Mark Beech is the Bloomberg’s chief rock critic. He is also Europe and Asia team leader of Muse, the arts and culture section of Bloomberg. He is the author of “The A-Z of Names in Rock,””The Dictionary of Rock & Pop Names”and “Culture Shock”(forthcoming).

[/note]