The Divine Comedy

September 2, 2012

A Planet in Crisis: Can Art Save Us? Is it even trying?

September 2, 2012While attention to the natural environment is critical, it is easy to forget – or indeed not to realise at all – that our environment as humans is also a made thing. For humans as a whole, in fact, our environment could be said to consist of the natural world where we find ourselves and what we’ve made of those natural surroundings, our interaction with them. As is usually the case, such concepts come clearest to us through art.

Barbara Wildenboer

A

As environmental awareness garners increased attention within popular collective consciousness, there exists a tendency towards viewing the environment as a dislocated entity; as something separate and removed that warrants preservation but is ultimately heterogeneous. Often, the definition of environment in this context refers specifically to the natural environment, at the expense of the additional applications of the term.

With this in mind, the title of Brundyn and Gonsalves’ exhibition, “Implemented Environments” alludes to an active and personal engagement with differing notions of environment on the part of the participating artists. Thus whilst the exhibition is certainly imbued with a “green” conscience (evidenced particularly in the work of Sean Slemon, Jan van der Merwe and Barbara Wildenboer), this by no means comprises its sole focus. Rather, emphasis is on the interrelatedness of varying concepts of environments and the artists’ relationship to these external factors as something active, shifting and mutable.

To this extent, the qualifying term “implemented” is key, implying a sense of agency or action and indeed all of the artists within the exhibition demonstrate this in a manner relevant to their practice. Thus the “implemented environment” becomes something that one experiences, but also something that one perpetuates and has the potential to influence; environment as an entity sustained by a series of actions and reactions.

Slemon’s Public Property (2010)

Implicit in the assertion of action/reaction is the notion of consequences, bringing to mind the work of Sean Slemon and Barbara Wildenboer. Slemon’s Public Property (2010) incorporates a concept of implemented environments through an examination of the paradoxical existence of nature within an encroaching urban environment. As a specifically constructed entity that has to be planned, planted and accommodated for, there is nothing fundamentally natural about trees (in this instance) within the public sphere. Yet at the same time, it marks a necessary incorporation of nature into the urban landscape both for physical, psychological and environmental reasons.

Isolating and taking apart a diseased elm tree, Slemon’s series of video stills resembles a set of assembly instructions, reducing the tree to a generic constructible public space prop. This conflict between the natural and urban environments is further emphasised through the conceptual drawing Disappearing Tree- Nature Engulfed in Urbanity (2009). As the depicted tree, felled by Slemon’s signature red ribbon (a subtle allusion to bureaucratic red tape?) is erased, it is usurped by cement, polyurethane and soil.

A term with practical application throughout the exhibition is the neologism “solastalgia” (coined by Glenn Albrecht in 2003 and cited by Wildenboer in relation to her work). The term refers to psychic or existential distress resulting from environmental changes and

… the pain experienced when there is recognition that the place where one resides and that one loves is under immediate assault … a form of homesickness one gets when one is still at “home.”

Within the context of Wildenboer’s Organism/Environment (2011) series this is related to the plight of the endangered South American hummingbird.

Produced on a residency to North Colombia, the series of prints depicts taxidermied hummingbirds on loan from the Museum of Natural History, albeit with their wingspans replaced with wings fashioned from pages of the atlas relating to their indigenous environment. The compounding effects of deforestation and chemical pollution have jeopardised the livelihood of these hummingbirds, hence Wildenboer’s citing of solastalgia as a relevant concept. Subsequently, the taxidermied hummingbirds may one day have to function as a surrogate for the living birds, a disturbing notion mimicked in Wildenboer’s second level substitution of the bird maquettes for prints bearing their image.

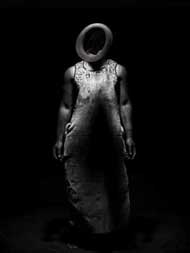

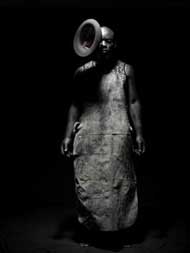

An assumption of Albrecht’s solastalgia is the perception of a stable starting point, a notion challenged by the autobiographical protagonist of Mohau Modisakeng’s triptych C-print Untitled (2010). The work functions as a visually striking interrogation of the artist’s identity within a complex heterogeneous, social environment. Moving towards a more socio-political view of environment, Modisakeng emphasises the postcolonial premise that the circumstances and structures that have resulted in historically silenced voices cannot be ignored and their reality must be specifically acknowledged if one is to come to terms with and alleviate the underlying structures that perpetuated them.

Mohau Modisakeng’s triptych C-print Untitled (2010) |

Mohau Modisakeng’s triptych C-print Untitled (2010) |

Mohau Modisakeng’s triptych C-print Untitled (2010) |

In order to understand the individual’s role amidst the confusion of mangled underlying historical structures, the personal archive of experience must be unpacked. Assuming an active stance, Modisakeng explores this through visually isolating himself; nothing remains in the achromatic liminal void except for the artist and the symbolic representation of his identity.

Similarly displaced within a void are the floating crystals of Daniella Mooney’s Obscured by Clouds (2010). Taking its title from Pink Floyd’s soundtrack album to French director Barbet Schroeder’s 1972 film La Vallée, the fragmented sculpture’s constructed qualities quite literally present an implemented environment complete with trees and lampposts. That the inhabitants of said environment are absent raises numerous questions (have they suffered a similar fate to Wildenboer’s hummingbirds?).

The protagonists of Schroeder’s film are in search of an untouched utopia nestled within an area demarcated as “obscured by clouds” on the map. Viewed in this light, the lampposts can be read as an encroachment of urban development upon a natural environment; an inversion of Slemon’s elm tree. In addition, the question of function arises too. Lampposts serve as a means of assisting navigation or traversal of a darkened space with light, perhaps one’s existence in this environment is intended to be transient. There is indeed a sense of parallel dimensions, an inherent duality emphasised in the mirror-like symmetry of the piece.

Playing on the history of implemented environmental factors such as fire and sunlight, the role of light in shaping perception is similarly central to Jessie Hammond’s contributions; realised in a series of ash monoprints of lighthouses (a key example of light facilitating the perception of a space) and constructed “projector contraptions”. Recalling Francisco Tropa’s ‘Scenario’ exhibition at the Portuguese Pavilion at the 54th Venice Biennale, Hammond’s projectors extend the tradition of “magic lanterns” (an ancestor of the modern slide projector, developed in the 1600s, which utilised an oil burner or candle for its light source).

Using bulbs as the source of their light, Hammond’s projectors reference the history of utilising fire for projection light by exposing the slides to flame; capturing smoke on the glass and then delicately rearranging the residual into the desired image with a needle. By including both lighthouses (structures that reveal through light) and projectors (structures that create an illusion through obstructed light) Hammond has astutely put into play Plato’s quintessential allegory of philosophical enlightenment, the Allegory of the Cave.

The notion of carbon remnants (implicit in Hammond’s smoke and ash) resurfaces through the use of charcoal in Jan van der Merwe’s conflicted Drag Marks/ Sleepmerke (2010), a sculptural work created entirely through “post-tree” materials (wood, fibre paper, charcoal). Resembling a forensic crime scene (a reading easily applicable to Slemon’s Disappearing Tree also) the work contains an artist’s book of charcoal drawings detailing the progressive dragged removal of a tree stump in a state of mid-metamorphosis into a chair. As the chair-stump is dragged over successive pages it ultimately joins the marks on the rest of the table (on which the book is placed.)

As such the work draws attention to the post-mortem arbor mutilation inherent in its materials, yet finds itself unable to condemn this due to the productive purpose that they serve This is a sentiment van der Merwe is unable to extend to the spoils of poaching, harshly criticised and parodied in his Trophies/Trofees series (2010) through a substitution of typical poaching/hunting trophies with rusted tins.

Wat Ga’aan 2011

Zwelethu Mthethwa and Willie Bester’s

An alternative reading of this work equates the weathered tins to rusting, decayed Ozymandias-esque trophies of consumerism. The two photographic subjects of Zwelethu Mthethwa and Willie Bester’s collaboration Experiment 5 … Wat ga’aan (2011), whilst on the periphery, seemingly find themselves similarly in the realm of found objects; sifting through the remnants of consumer goods for that which can be subsequently recycled or recontextualised.

This gesture is enacted within the work itself through the presentation of found rusted cups as art objects in a mirrored display or the inclusion of the motherboard and circuitry in the top-left corner. The presence of these mixed media components also allows the work to transcend photographic “flat death” and instead bestow a sense of depth and presence upon the viewer.

Indeed, an apt summation of the ideas surrounding ‘Implemented Environments’ is provided by the shattered pressure gauge in the lower left-hand corner of Mthethwa and Bester’s work. Whilst the source of said shattering is left abstract – be it attributed to climate change, urban sprawl, socio-political unrest or all of the above – the primary implication is a reaching and crossing of a threshold. This is further emphasised through the phrase in the title “Wat ga’aan”; derived from “Wat gaan aan” or “What’s going on?” Evidently this is a question that plagues all eight of the artists on this exhibition.

All images are Courtesy the artist and Brundyn + Gonsalves, Cape Town. SA

www.magiclantern.org.uk/history/history4.html