Green Rock

September 10, 2012

OBAMA, where art thou?

November 4, 2012

Malina

While last year’s devastating floods may be a receding memory for some, they did leave many in Thailand pondering more seriously on humankind’s effect on the environment and its effect on us. For architect Malina Palasthira, however, such concerns are of everyday, fundamental importance.

C

Conversation with an architect, especially in Thailand, can be all about form. Discussion invariably focuses on what a building should look like. Traditional Thai? Modern? Baroque? Tropical Colonial? Art Deco? Tell them what you want and they’ll build it for you.

While it would seem perfectly reasonable to approach designing a building based on how one wants it to look, Malina Palasthira of Thai architectural firm Design Qua Ltd. is more mindful of how a building functions. Is it appropriate for the climate? Does it work with the local topography? Is it a commercial or residential site? If residential, how many people will live in it? And what of the relationship between those residents?

Over dinner with her husband John Erskine, who is on the thesis committee at the School of Architecture and Design at King Mongkut’s University of Technology, Malina makes clear that effective architecture must always address issues beyond the cosmetic. It must, she maintains, fully take into account intellectual and philosophical matters.

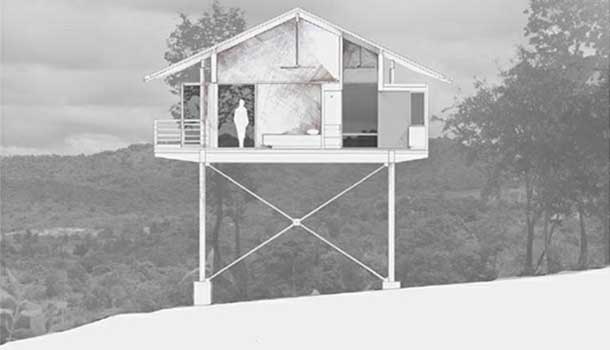

Cross section of the house

Unfortunately in Thailand, such matters too often give way to surface concerns. Thailand is home to such architectural oddities as the Robot Building and the Elephant Building.While one doesn’t dispute that such edifices have their impact, conceptualising architecture from appearance alone can lead to a skyline that, although definitely interesting, may evince something more cartoonish than majestic. Would anyone call the Elephant Building great? And in that vein, what makes for a great building? Moreover, from a standpoint beyond the merely aesthetic, what makes for architectural success?

This Is the Modern World

Conversation with John and Malina is passionate, stimulating, intelligent, at times challenging but always entertaining. He was brought up in the Washington, DC suburbs of Northern Virginia, studied in New York and then worked in Southern California, where he and Malina met. John’s is a quieter, more measured voice in the discussion, a perfect counterpoint to Malina’s passion and fervour. The daughter of a peripatetic, westernised Thai father and an Italian mother, Malina was brought up in Thailand. Her early years included many trips abroad followed by education and training at the University of London and then the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She worked for a number of years in Los Angeles.

To Malina’s way of thinking, effective architecture abides by the tenets of Modernism. Her heroes are Glenn Murcutt, John Lautner, Louis Kahn and Carlo Scarpa. “Modernism,” Malina says, “is not just an aesthetic, but an approach to design. It loosely follows the early ethos ‘form follows function’ [articulated] by Louis Sullivan.”

“Modernist architecture can vary widely,” she continues, “from the minimalist, austere and monumental work of Tadao Ando to the Hollywood whimsy of John Lautner. It’s the cultural expression of early Western industrial society and it has now evolved and adapted to respond to our post-industrial world. It was, and still is, an approach to design and architecture that celebrates and integrates technological innovations into the environment.”

Malina is quick to point out, however, that Modernism isn’t always about being high-tech. Modernism can also be about using old materials in new, creative ways that better reflect the way we live today.

“The branch of Modernism that inspires me most,” explains Malina, “is Critical Regionalism, which has been practised since the beginning of the Modernist movement, in parallel with better known architects like Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe.” This is a kind of Modernism that respects its immediate natural and cultural context. Even some of Le Corbusier’s better projects can be argued for as Critical Regionalist. Early proponents of this type of Modernism are many of the Scandinavian architects, such as Alvar Aalto and, more recently, people like Sri Lankan Geoffrey Bawa and Portuguese architect Álvaro Siza.

“One of the biggest drawbacks of early Modernist buildings is how they have not held up over time,” Malina continues. “Even the best examples of these have aged horribly. This is partly because almost a century ago these pioneer architects were experimenting with completely new materials – steel, glass, concrete, aluminum – that had not been time-tested as materials before. A great example that now looks a bit tired, but was very innovative in 1950 as a prototype of a prefab house for the tropics, is La Maison Tropicale by Jean Prouvé.”

Site Specific

Taste, then, is not the sole factor affecting a building’s longevity. Another factor is the environment and how well construction materials endure. In tropical climates, structures can be affected by heat, humidity, strong ultra-violet rays, insects and many more.

“The sun plus humidity is what kills materials,” notes Malina. “Things expand and contract. The humid, tropical climate in a big city is the most difficult factor. Tropical cities have no wind, and the only way to cool a building down in this climate is with the wind. All the concrete in a city absorbs heat during the day, but in the evening the heat doesn’t dissipate. It actually gets warmer because of all the heat released from the concrete. This is called the heat island effect.” And it is, says Malina, something that architects in Thailand must better address.

Given Malina’s eloquence on Modernism and how architecture should consider a specific region and its ecology, it’s not so surprising to know that she and John live in a traditional Thai house they’ve adapted for modern use. The structure features natural materials complemented by sustainable-technology elements such as rain water capture for domestic use.

3D rendering of dwelling’s pool

“All vernacular architecture,” states Malina, “is an adaptive response to its surrounding context – the environment, the climate, the materials available. The design of traditional houses is based on culture, on years and years of trial and error. Traditional Thai architecture is low-tech, but smart.”

3D rendering of dwelling

Does Malina have any favourite traditional Thai buildings?

It turns out good examples of traditional Thai architecture are not unlike those of the early Modern movement. There aren’t many left. Malina says, “It’s difficult to find houses that are old and well-preserved, but I like Baan Sao Nak in Lampang, which is rustic and beautiful. As for temple compounds, Wat Phrathat Lampang Luang is pretty stunning.”

The ideal architecture for Thailand, Malina feels, is traditional. “I think, before the latter part of the 20th century, we were progressing quite well with traditional architecture. We had real artisans who worked with wood and then – boom – came air conditioning. We got cars and concrete. This combination of concrete and air conditioning killed tradition. Basic elements of tropical architecture – pitched roofs, large overhanging eaves, big windows and elevation on stilts – worked, but as soon as air conditioning came in, these traditional elements disappeared from our buildings. The traditional craftsmen became unemployed and anyone who could pour concrete became a builder.”

Technology like interior climate control gave us the impression that it didn’t matter how a building was designed because it could always be made comfortable. Abandoning traditional designs led to even more heat given off by air conditioning condensers and exacerbated the heat island effect.

The issue of sustainability is, therefore, an important one. How can one build a modern, sustainable building in Thailand? Malina is adamant when she tells us, “You can’t fight water, you can’t fight the elements. You might as well work with them.”

Buildings like traditional Thai houses have been adapted over generations for the local climate and those adaptations shouldn’t be dismissed. Peaked roofs make for good drainage, overhanging eaves keep out the sun and rain, large windows allow for good air circulation and elevation on stilts prevents flood waters from entering the house. While some may see such design elements as merely aesthetic, they are also adaptations to the environment that should be respected.

The Postmodern Dilemma

It seems quite obvious that there is a right way and a wrong way to build for Thailand’s climate. How, then, does one explain the buildings there are that seem preoccupied with design elements but that don’t necessarily function,along with the fascination with architecture that doesn’t necessarily work with the local environment?

Malina blames the Postmodernist reaction to Modernist design. “Post-war architecture ruined Modernism,” she says. “After World War Two, they built a lot of Modernist buildings quickly and cheaply. They reduced modernism, took out the details. The Postmodernists, in a reaction to such architecture, sought to design buildings that made references to the architectural vernacular of the past by emphasising the way a building looked. Architectural elements were added to a building’s design so that it looked interesting, but functionality suffered because it became a factor of technology – like air conditioning – as opposed to design.”

For all its paring down of detail, Modernism is about making buildings that work well for the people using them. As Louis Sullivan said, “form follows function”. So when an architect turns away from how a building functions to how a buildings looks, it is, Malina declares, “completely irresponsible urbanistically, because every building in a city, every urban structure, has a responsibility on the street level. Postmodernism is all about making fun of traditional visual references, but it kills people’s experience of the building.”

|

|

| Malina and her husband live in a traditional Thai house, which they have adapted for modern use | |

While people may enjoy looking at such buildings, they are often unable to relate to them. Indeed, how often does one find oneself approaching a building without being able to find the door?

Malina, who has spent a fair amount of time in Italy, finds that Italian cities are the most people-friendly not because of design elements – which are often aped by Postmodern design – but because of functionality. “The Postmodernists like to use Italian references. They like to do Neo-Classical stuff but lose the ability to relate to people. If you go to Italian cities, they have the best urbanism on the street level. The streets are amazing because the scale is easily related to. There’s the portico that blocks you from the rain or sun. There’s the shops that are there on the ground floor and you live above. It’s the best kind of shophouse. The motifs don’t mean anything when it’s the actual function that is important.”

After a long meal, a bottle of wine and then dessert, we settled into a conversation that touched on working with clients and conceptualising projects. What is Malina’s approach?

“I enjoy taking ideas and suggestions from the client, but going with it further, getting together with the client and having the idea actually grow. And from that, the client’s dream grows. It’s still what the client wants. It’s the way they want to live,” Malina says. “There should be a symbiotic relationship between the client and the architect.”

[note]

Courtesy of Cat & Nat – www.catandnat.com

[/note]