The Three Billion Club

February 15, 2013

Empowering the Blind in Nepal

February 15, 2013Those who forget the past are condemned to repeat it – or so it’s said. But what of those who don’t simply forget the past, but actively squelch it, erase it, stamp it out, revise it? Perhaps they don’t just repeat the past, but live it, as a continuing – a still-threatening – present. “It must never happen again” cannot become a healing reality if people insist “It never happened at all.”

S

So in what country can a World War II Nazi sympathiser, fascist quisling and war criminal get a state funeral in 2012? Here’s a hint: it’s the home of a now-infamous heckler at the recent Summer Olympic games, who made monkey noises, placed a comb over his upper lip, and gave Hitler salutes when he spotted black basketball players on the court. He then stood before a not-amused British judge after being arrested and stated in his defence that this was “perfectly acceptable behaviour in my country.” His country, incidentally, is one where Jewish graveyards and synagogues are routinely vandalised with impunity, and where one of the largest neo-Nazi marches in recent memory took place, with virtually no opposition.

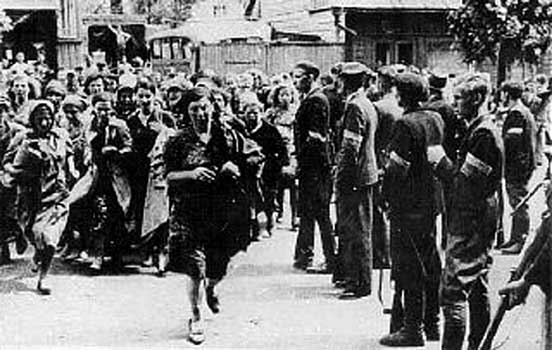

Jews being led to execution Kovno 1941

You might be surprised to learn that the location in question is Lithuania, which is per capita one of the best educated nations in Europe. It is a credible democracy and member of the United Nations, NATO, the OSCE, the Council of Europe and a signatory to all of the human rights conventions that go with them. But this past May 17th, a white-gloved military guard of honour, the Lithuanian Army Orchestra, former president Valdas Adamkus and Catholic Archbishop Sigitas Tamkevicius were present to render an official homage to the repatriated remains of wartime prime minister and Nazi puppet Juozas Ambrazevicius-Brazaitis.

Jews beaten to death by Lithuanians with iron bars, Kovno 1941

A solemn memorial service was held and the collaborationist leader was reburied in the Church of the Resurrection in the city of Kaunas. The Archbishop lionised Ambrazevicius-Brazaitis as a man “who loved Lithuania and loved God.” The mayor of Kaunas, Andrius Kupcinskas, is adamant that the ceremony was nothing untoward, and the current president, Dalia Grybauskaite, isn’t saying much at all.

To their credit, individual Lithuanian parliamentarians, academics and journalists decried the spectacle of this official adulation and hero’s welcome for Ambrazevicius-Brazaitis, but they represented only a handful. One couldn’t say the event prompted a national outcry or a vigorous debate and certainly no deep soul-searching in the nation’s collective psyche.

So where is the sin of omission? What did Ambrazevicius-Brazaitis and his contemporaries do that was so terrible? For historians of the Second World War and scholars of the Holocaust, the conclusion is chilling, incontrovertible and widely documented: nothing less than actively helping and enabling the occupying German forces to launch the Final Solution in the Baltic, well in advance of the wide-scale industrialisation of the genocide elsewhere and before the network of death camps ever existed. This ultimately resulted in the near total annihilation of Lithuania’s Jewish population between 1941 and 1944. In the first year of the German occupation alone, German death squads and their allied Lithuanian auxiliary police forces and militias killed some 175,000 Lithuanian Jews. In the first six weeks following the German arrival, the Lithuanians themselves killed 10,000 Jews. In fact, Lithuanian mobs and paramilitaries had started murdering Jews en masse, before German troops and police did. And it was Ambrazevicius-Brazaitis that had signed the legal documents giving them authority to do so, legitimising the horrors that followed. Lithuania’s forests echoed with the sound of firing squads and its old castles and fortresses, like the Seventh Fort in Kaunas where 30,000 were executed, became both detention centers and killing grounds. Ambrazevicius-Brazaitis had rubber-stamped the Holocaust. In a tangible way, wartime Lithuania can be regarded as the very beginning of the Jewish genocide in its physical application, in what has been called the “Holocaust by Bullets.”

Lithuanian Militia rounding up Jews,

Kovno 1941

Ambrazevicius-Brazaitis was not remotely a reluctant collaborator either. He was a fawningly enthusiastic and sycophantic one. His personal correspondence with German occupation officials is laden with lavish praise and adulation for his newfound masters and the greater Third Reich. If he wasn’t officially a Nazi, he gave an excellent impression of one.

Lithuania had a population of three million, 210,000 of whom were Jews. Of those, 196,000 would be murdered, some eventually shipped to the death factories, but most dying on their own soil, at the hands of their compatriots. Lithuania became such an efficient killer of Jewry that Vichy-led France even sent two trainloads of its own Jewish citizens to die in Kaunas.

Jewish Children, Vilnius Ghetto

What distinguished Lithuania was the widespread participation of its people in the slaughter: in thought, in acquiescence, in very deed. As elsewhere throughout Eastern Europe, antisemitism was rampant and entrenched in Lithuania. Though only 1% of Lithuanian Jews were members of the Communist Party, there was a widely accepted belief that Jewish Communist fifth columnists had played a key role in the Soviet Union’s annexation of Lithuania in 1940. It was a pathology both Lithuanian nationalists and Nazi propagandists whipped into an effective and murderous frenzy to cleanse the perceived enemy within, when Germany attacked the Soviet Union and conquered Lithuania once more. Having themselves suffered terribly under Stalin, the Lithuanians greeted the Germans as liberators and soon vented their thirst for vengeance upon the easiest target, encouraged by their new occupiers, who were surprised and pleased by the Lithuanian zeal for the slaughter.

Germany never raised SS units from Lithuanian volunteers as they did in neighbouring Latvia and Estonia. A fledgling, German-sponsored, Lithuanian proto-army was organised but did not last long. However, the numerous Lithuanian security police formations established by the Third Reich saw service in occupied Poland, Russia, the Ukraine and Belarus, as murder squads, counter-guerrillas hunting partisans, repressing civilians and guarding prison and death camps. There the Lithuanians earned a reputation for cruelty documented in many Holocaust survivors’ diaries and oral testimony.

Ponary massacre 1943

Records do show, in contrast, that 100 non-Jewish Lithuanians were executed by the Germans for trying to help or rescue Jews. An additional 723 are remembered as “righteous” people in the archives at Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust Museum, honoured for having saved Jews despite the risks. And there did also exist a small, armed resistance movement against German occupation, composed of Communists and non-Communists alike. But Lithuania was not like Denmark, Norway, Belgium or Holland, where the resistance fought on behalf of all citizens. Indeed, in Denmark virtually the whole Jewish population was saved by the underground. Lithuania, through the cold prism of history, was more like a virulent Baltic version of Vichy, Lilliput soaked in the blood of its own people, in no small measure done by its own hands. Yet if one considers the whole course of the war – the Soviet occupation beforehand and re-occupation after the German withdrawal, the mass deportations to the Gulags that ensued, renewed guerrilla resistance to the Soviets, and the destruction wrought by battle – Lithuania did pay dearly for its allegiances, its mistakes, its geographic location, its aspirations, its prejudice and the sheer tide and fluid fortunes of conflict. Catholics and Jews together, a total of some 780,000 Lithuanians, perished – a near genocide in itself. The casualties included tens of thousands of soldiers press-ganged into the Red Army. Precise figures are hard to come by, but perhaps another 60,000 died at Soviet hands in the post-war period as fighters or prisoners. Essentially one fifth of the population underwent deportation.

But there lies the rub, the conflation of all this tragedy, the blurring of causality and accountability, which is precisely the malady distorting modern Lithuanian memory, as it looks back on itself. It is an all-but-transparent effort to re-write history, to highlight moments of glory and courage, and to bury the shame. The legacy of victimisation is the key to airbrushing the stain of fratricide during the Second World War. A modern post-Soviet Lithuania, fully integrated in the European Union, is still a nation under construction, shaping itself and with it, the national mythology that it deems palatable, as any other country would do. The most potent building blocks of this tale are how it fought tenaciously for its independence after the First World War (which it did); how it resisted the Kremlin’s yoke throughout the Second; and, with the fall of the Communism, having been an insurgent state all along, how it earned the moral right to regain its place as a proud and independent people with an ancient cultural tradition and a once-grandiose past as a ducal state when it had ruled much of Europe.

That’s a legend everyone can live with. Indeed, the tale of the anti-Soviet guerrilla movement and the hardy Lithuanian partisans who came to be known as “Brothers of the Forest” is a truly epic tale of courage, devotion and sacrifice. The Brothers fought as ferociously as Tito’s partisans ever did, except they continued well into the 1950s, largely ignored by the outside world. The last of them, still holding out and committing suicide rather than face capture, died – a rebel to the last – in 1965! Outside of Lithuania, this is largely an untold and unknown story, surely one of the most heroic in the history of all resistance movements.

Lithuanian militia man,

Kovno

The problem is that it’s not the whole story. Official government-sponsored investigative studies of both the German and Soviet eras are top-heavy with accounts of Soviet abuses and conspicuously light on references to the enthusiastic Lithuanian collaboration with Nazism, and fervent participation in the Holocaust.

But who would want to remember such crimes publicly? Who would want to acknowledge that many of Lithuania’s guerrilla heroes were rabid antisemites, not a small number of them having tasted first blood in German service or in homegrown pogroms? And so we’re back to the hagiography of Ambrazevicius-Brazaitis once more, the most recent phenomenon of selective memory: the celebrated rehabilitation and reinterpretation of a Nazi-admiring collaborator and enabler of genocide and his elevation to national hero. In the new canon, he wasn’t a racist, bloody-minded toady of the Nazis. He was rather, a patriot, doing what was best for his people and his country; keeping alive some semblance of self-government and independence; sowing the future seeds for a reborn Lithuanian state.

Remains of Ambrazevicius

return to Vilnius

Ambrazevicius-Brazaitis was not a hero. He was a mass murderer, guilty of crimes against humanity, who, by rights, belonged in the dock on trial at Nuremberg and then on the gallows with a noose around his neck, like the other convicted Nazi architects of unspeakable horror. Somehow he escaped justice and died peacefully as an immigrant in the United States and now rests enshrined as a national hero in a tomb fit for a gallant knight errant of old. It is a desecration of both the truth and of history and it does not move Lithuania forward into the future as an equitable and mature partner in the community of nations. Nor does it help educate a younger generation of Lithuanians to avoid repeating the grave mistakes of the past, or to abandon an especially malignant form of racism. Instead it leaves Lithuania open to the persistent accusation that it remains one of the most intolerant and deeply antisemitic societies in the whole of Europe. Moreover it gives renewed hope to every revisionist and Holocaust-denier still able and willing to tell the great lie.

If a lie is told long enough and well enough, it may begin to have the ring of truth for those who’d prefer not to see the truth in its entirety. Lithuania’s painful ordeal under the crushing brutality of the Soviet Union, cannot, should not, and will not erase the ugly stain of wartime Lithuania’s atrocities and crimes. The suffering of one does not cancel out the evil of the other, when the victim of the first is also the perpetrator of the second. You don’t get a clean slate when you commit genocide. You can only heal that wound when you own up to the truth. Until Lithuania is prepared to do so, we must ask: does it deserve a place at the European table and the community of civilised nations?

[note]Photos courtesy of Defending History.com[/note]