Roger Ballen / Die Antwoord

February 14, 2013

The Three Billion Club

February 15, 2013A design-led society or society-led design? As we move ever closer towards a new world order in which humanism and technology can happily coexist, which one has the potential to lead us into the future?

Original design, in its purest sense, was born out of human needs – a necessity of finding a way of making something work, a development of process or just a helping-hand to make life a little easier for everyone. As society has developed, so too have the tools and instruments used to produce goods that – in turn – have enabled us to progress even further in our struggle for survival and then dominance.

Nowadays, it seems as though there are thousands of extraneous products being launched in the developed world every year. So maybe the future of design is to follow where society is leading. Technology is at the forefront of this transformation, however, and is bringing the world within reach of us all by providing us with an astounding amount of information at our fingertips. It is little wonder that humanity’s desire to evolve is pushing design to its limits in order to keep pace with us. As we become more and more interconnected, it is easy for people to see what they do not yet have, but already covet.

Ernest Race,

BA-3 chair

In the early 1970s, one designer sought not to refute technology nor shun its capabilities, but rather called into question the designer’s position on social and ethical responsibilities in the development of that technology. Victor Papanek believed it possible to instil a sense of social accountability into the work being produced. In so doing, Papanek anticipated, by some twenty years, the advent of Appropriate Technology. This is the idea that through small-scale, local initiatives, technological benefits could be felt immediately by those most in need. It is a model that has been adapted and taken around the world with varying degrees of success, but one factor is common throughout – each project has been driven by the requirements of the local community. Those requirements can be explained by any number of factors determined by local conditions, yet all aim to achieve the same desired outcome, namely, an improvement within society through design.

Hans Wegner

Elbow chairs, 1949

It was the antithesis of the looming zeitgeist of the times, epitomised by the British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher when she deliberately stated “there is no such thing as society”. That remark did not hold sway in many parts of the world, not least the Scandinavian countries of Sweden, Denmark and Finland. With their traditions and belief in crafting as a way to explore the psyche, they have long been associated with human ideals of design and the empowerment it affords the user. Designers from Sweden in the post-war years measured and calculated the basic standards required for living, at a time when adhering to the values of democracy and egalitarianism were so important to the world. The results enabled people to live a more connected existence and provided them with a sense of well-being and happiness within their own homes. The limiting of materials and pure, almost sculptural, qualities of the work gave rise to what is now universally acclaimed to be “good design”. Furniture from Hans Wegner or glass from Tapio Wirkkala were seen as vital enrichments of daily life rather than status symbols. They spoke of a unity between technology and craftsmanship, allowing communities to focus on new ways of seeing and living with one another. The relationships that were forged across a shared sense of ownership and neighbourhood began to govern the wider community and influence civic design in towns and cities across the region.

Tapio Wirkkala Chanterelle Vessels

for Iittala, 1955

Workplace and communal spaces were just as important, with most local authorities throughout Europe having their own departments governing architecture and municipal design. The aims and aspirations people had sought inside their own homes, were now being played out on a grander scale in the community.

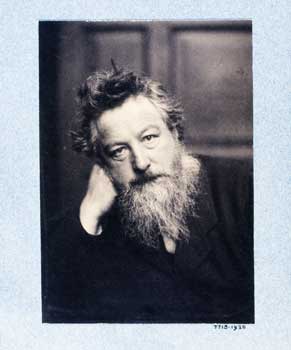

William Morris

This social awakening was not a new phenomenon. Eighty or ninety years earlier, British artist, designer, and socialist William Morris was striving for the same ideals. In 1871 and again in 1873, Morris visited Iceland. There he saw for himself the uncomplicated arrangement of a classless society, aided and supported by the national assembly at Thingvellir, the oldest of its kind in the world. The experience was to inform his future writings on the inseparable links between the applied arts and society, those which forged cooperation and gave man his creative freedom.

Sadly for Morris, his writings and musings on a socialist utopia were overtaken by the popularity of his work, and those who he had long fought against – the Victorian Middle Class – became his main supporters.

Festival of Britain poster

In Britain, it would take another sixty years before design became a central part of the government’s policies for society. With the advent of the Utility Furniture Scheme, ministers sought to develop and instruct the public’s taste with a rational and simplified approach to design. It was, however, too closely linked with austerity measures, and an overwhelming public reaction forced the closure of the scheme in 1952. It was all too reminiscent of the brief flirtation Britain had experienced with Modernism in the 1930s, when Louis Sullivan’s maxim of “form ever follows function” had captivated the imagination of a youthful and vigorous society. Tradition and comfort were too heavily ingrained in the British psyche to relent. Despite the popularity of exhibitions such as “Britain Can Make It” or the “Festival of Britain”, the love affair with the all-encompassing demands made on life by Modernism, came to an end. Society was, by the middle of the Twentieth Century, asserting a wanton desire to consume the things it wanted, rather than merely cope with the things it needed.

From the colours and playful shapes of popular America in the 1950s and the vibrancy of psychaedelic London in the 1960s, designers were now producing goods as a means of conveying the attitudes and values a younger generation had come to represent. Design for consumerism would last another thirty years globally. In spite of the oil crisis, the three-day week and the national strikes, we wanted nothing more than all those things we couldn’t afford. During the 1980s, society had become a victim of its own desires, during what is now seen as the “designer decade”. Anything which could be consumed, could be labelled “designer”. The industry was selling itself to the farthest reaches of society and perpetuating its own self-fulfilment.

However with the coming of the 1990s, we had begun to look beyond our own selfish wants and to reflect on the needs and the purpose of design within society. Even the most notorious and fickle of the design industries – fashion – had stripped itself bare of the excesses and returned to a more holistic approach, with numerous couturiers sending out rows of models to the catwalk in all-white creations, symbolising the renewed state of a clean and virtuous society. The context of design was changing as “Green” movements gathered momentum and a global conscience was awakened to what we had been doing to the world’s resources. We began to see we had a duty to protect and care for the world, for society, for ourselves.

As we settle into the 21st century and are all a little more comfortable with omnipresent technology, we understand the context of design within society as well as how it helps to shape our individual positions amongst that society. Education, healthcare, housing and leisure have become the most prevalent sectors willing to embed a human scale into their development. Schools in the UK are being designed with large, open, airy communal spaces, where children of all ages can gather and socialise. Such designs can be directly linked to the open and democratic assemblies of Iceland, Sweden and Denmark – where everyone has a place and there is a place for everyone.

Hospitals have realised the value and importance of colour to aide recovery times for bed-ridden patients meaning a faster turnaround on wards. This, in turn, enables greater numbers of patients to be treated by the hospital in general. Gardens are incorporated into hospital design for scent and texture and to encourage interaction and recuperation.

Housing cooperatives and self-build schemes have proliferated in the past ten years as a reaction to the box-like properties developers have erected on the pretext that that is what the public wants. Fortunately, some enlightened clients still exist in the economic depressive era we face and are willing to fund experimental architecture and design as a means of improving life. In Denmark, architect Bjarke Ingels and his team completed the 8House project in 2010. This is a mix of residential and commercial properties which, in their words, offers “homes in all its bearings for people in all of life’s stages: young and old, nuclear families and singles, families that grow and families that become smaller.” Our world is no longer made up of two-parent/two-child units. The architects of our communities must recognise and reflect this shift when designing for society.

Cultural behemoths such as the V&A in London or the spectacularly successful Guggenheim in Bilbao show what a transformative effect design can have on a city or indeed, an entire region. The economic benefit to the Basque country in the first three years alone was said to have been worth an estimated €500 million.

With such tangible results, design has been able to provide society with an understanding of what it can do for us and how it helps to shape our communities. It is because of these experiences that we have been given the confidence to ask for what we need of the industry and displays the symbiosis in which society and design coexist together. It is up to all of us to continue to foster this relationship and ensure that as technology develops, none of the world’s communities lose out on benefits in the future.