The Divine Comedy

February 14, 2013

Design With a Conscience

February 14, 2013Born out of the ashes of a small scheduling disaster, the strange – yet somehow fitting – collaborative exhibition by photographer Roger Ballen and musical duo Die Antwoord draws raves in South Africa.

by Heidi Rasch

The Photographers Gallery za in Cape Town had planned to host Roger Ballen’s Boarding House exhibition in 2010. This particular series had been on view at most of the major art centres across the world. What was of particular interest was the announcement of a major Roger Ballen exhibition at the Iziko South African National Gallery in Cape Town during 2010 as well. This was a first retrospective of his work at this art museum. Once the date for the museum exhibition had been confirmed it was also made clear by the museum director, Mr. Riason Naidoo, that no associated commercial exhibition would be permissible during the duration of the museum show. Thus, the Photographers Gallery za had to cancel its long-planned solo exhibition. It was a disaster. Because the 2011 schedule had been confirmed, there were no slots available to postpone the exhibition to a later date. A better strategy soon emerged: cancel the Boarding House solo exhibition completely and start planning a new exhibition. It was during this upheaval when Ballen mentioned, almost in passing, that he had done some work with the musical duo, Die Antwoord.

Roger Ballen, Die Antwoord,

New York Times,

The Roger Ballen/Die Antwoord exhibition became a reality when a Month of Photography festival was confirmed for the last quarter of 2012. By the time we opened the exhibition, on 18 September 2012, it had been six years since Ballen’s first solo exhibition at Photographer’s Gallery za.

Roger Ballen, Die Antwoord 2008

Neither Ballen nor Die Antwoord was in South Africa much during the planning phase of the exhibition. This caused delays, but ultimately did not affect the vast numbers of visitors who turned up for the opening night reception. Shortmarket Street is a pedestrian street; it was filled with visitors, many of whom never managed to get in to see the exhibition. The gallery itself was packed to capacity.

Ballen gave an opening address that provided an intimate and sobering insight into his approach to black and white photography – sobering in the sense that many people present at the opening knew very little about Ballen or his keen and deep interest in combining psychology with photography.

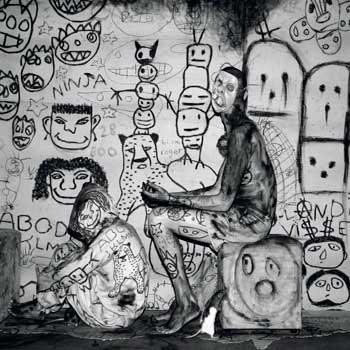

Room of the Ninja Turtles, 2003 P627

Roger Ballen, the artist, the photographer, has long been misunderstood by South African audiences. He was accused of exploitation at the opening of his first Cape Town exhibition in 2001. That attitude is still very much alive. Die Antwoord has a huge fan base, but they also have their critics as well. Folding the work of these creative individuals into one exhibition brought fans from both sides, as well as the critics. The gallery’s visitor numbers were the highest recorded in the history of this twelve-year old gallery. The exhibition was extended to 17 November to accommodate the volumes of visitors, but not even that was long enough. The media response was also unprecedented. The exhibition remained a news item for five consecutive weeks in the daily and weekly print and online media. Roger Ballen became a household name and Die Antwoord used the opportunity to launch a new song, “Fatty Boom Boom,” which instantly went viral.

Roger Ballen/Die Antwoord

installation view

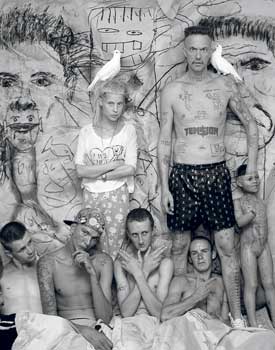

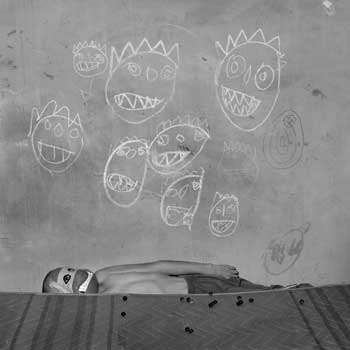

The regular white cube gallery was transformed into a dark ‘Ballen-esque’ space. Carefully selected photographs from his earlier series (namely Outland and Shadow Chamber) were also included. The main focus of the exhibition was the thirteen photographs featuring Die Antwoord. The centre of the installation is the music video of Die Antwoord’s hit song “I Fink U Freeky”, directed by Roger Ballen and Ninja. It won the award for Best Music Video at the twentieth anniversary event of the Plus Camerimage International Film Festival of the Art of Cinematography in Bydgoszcz, Poland in December 2012. This is the second major award for the video, which has received over 20 million hits on You Tube. It was also awarded the Music Video Grand Prix at the Curtas Vila do Conde International Film Festival in Portugal in 2012.

Visitors to the Roger Ballen/Die Antwoord exhibition felt compelled to discuss their interpretations of the material on display. The gallery’s visitors’ book is crammed with responses; one particular one is worth mentioning here. The viewer explained that visiting the exhibition felt like being present at the site of a car accident. There is so much pain and disaster. The visitor further notes, “Who does one rescue? Roger Ballen or Die Antwoord?” Such deeply emotional reaction to the exhibition was standard. The body of work elicited a huge response.

Roger Ballen/Die Antwoord installation Bath scene

Yo-landi Vi$$er of Die Antwoord has said, “We learned a lot from working with Mr. Ballen because he is a genius. He taught us that every single element in an image should mean something. You can stop on any one frame in the ‘I Fink U Freeky’ video and you will be looking at a perfect photographic image. That video is a masterpiece.”

Die Antwoord’s admiration for Roger Ballen’s work is well known and well documented. But what is Roger Ballen’s interest in Die Antwoord?

South African writer Ivor Powell gives his insights on this question:

The first thing to understand is that there is a fundamental lack of fit between Roger Ballen, photographer, on one side, and Die Antwoord’s Yol-landi Vi$$er and Ninja on the other. Die Antwoord is a project. It is a kind of extended joke or existential conceit. It exists only conditionally, as a hypothetical. It moves in the thin air of virtual reality, and only the irredeemably confused would be any more likely to confuse the public personas of Vi$$er and Ninja with Adri du Toit and Waddy Jones than they would Walt Disney with Mickey Mouse.

That doesn’t really need to be said. It becomes interesting though when you note that Die Antwoord subsists at what is essentially a new frontier of reality. Ninja and Vi$$er breathe a twenty-first century cultural air we have never really breathed before. This is not so much because of the actual underpinnings of the personas nor the transcendence of Zef culture. It comes from somewhere else. Commentators almost inevitably use the word viral when talking about the way the Die Antwooord brand (another one of those words from the twilight zone of post-modern metaphor) has grown from a single homemade video posted on the internet.

Roger Ballen/Die Antwoord installation, Gooi-Rooi

Viral? Literary laziness to be sure. But at the same time there is an insight inherent to the epithet: it has to do with a dynamic that is mysteriously exponential, uncontrollable, explosively mutative and quintessentially twenty-first century postmodern. At the end of the day it is the reception of the work – what its audience brings to it – that is the medium of expression. It is a participatory thing. What the producers of the work did to create it is just the starting point.

Now it is a no-hands, downhill ride; you don’t really steer, you just try not to fall off.

That is Die Antwoord. Ballen is something different completely. If Die Antwoord is the paradigm of the twenty-first century postmodern in its ephemerality and elusive dissociations, Ballen is just as much a modernist. His project as an artist is irreducibly tied up with the projection and exploration of self, in and through the work he creates. Starting out in the 1970s as a documentary photographer, Ballen, a native of the United States, focused first on small-town South Africa, the curious and already poignant – because already threatened, even doomed – half-life of South African whites in the platteland. Though certainly more aggressive in the way he approached his subject matter than contemporaries like David Goldblatt, Ballen, like them, entered into a dialogue with his subject in which the self is revealed in a response with the other.

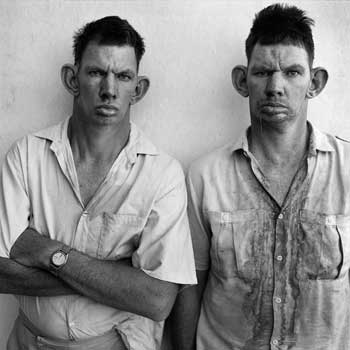

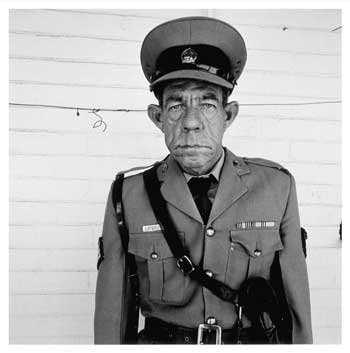

From there though, Ballen took some different existential turns. While there are obvious commonalities of style and intention between Ballen and American photographer Diane Arbus in observations like Dresie and Casie, Twins, Western Transvaal 1993 and Sergeant F de Bruin Department of Prisons Employee, Orange Free State 1992, there is also an internal logic that is especially highlighted in what happened to Ballen thereafter.

Roger Ballen, Dresie and Casie, Twins,

Western Transvaal,1993

Roger Ballen, Sergeant F de Bruin

Department of Prisons Employee, Orange

Free State 1992

Images like the two above are of the order of the freak show – at the extreme in their otherness. But there is more happening than just putting the subjects on the end of a pin. Ballen does not bring any particular empathy to his human subjects, but he does photographically engage with them, through eye contact and as sites of consciousness. In this, the dialogue of self continues undiminished. It just moves into a somewhat more psychologically extreme and ultimately more dangerous terrain.

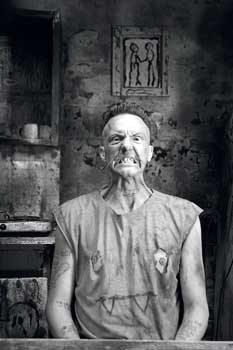

Then, sometime in the mid to late 1990s, there is a seismic shift in Ballen’s work. The dialogue segues into what is essentially a dramatic monologue. He stops defining himself as a photographer and instead starts thinking of what he does as art – not in any value-laden sense, merely to denote a different kind of activity. As Ballen himself puts it on his website, his later work is rooted in a sense that his chosen medium of black and white photography is “a very minimalist art form and unlike colour photographs does not pretend to mimic the world in a similar manner to the way the human eye might perceive. Black and white is essentially an abstract way to interpret and transform what one might refer to as reality.”

And he goes on to say his purpose in “taking photographs over the past forty years has been ultimately about defining myself… fundamentally a psychological and existential journey.” The key word here is one that almost disappears in the context: abstract. What Ballen, paradoxically and somewhat provocatively eschews in his later work is what common sense says is irreducible in the photograph – its concreteness, the fact that (except in the special case of images created exclusively by the manipulation of chemicals, light and emulsion, which is not at issue here) the photograph records something that exists separate from the photographer, in time and space.

The point is different. It has to do with the existential weighting that is given to what is recorded in the photograph on the one hand and the recorder on the other. What Ballen chooses to highlight is one pole in what is ineluctably a bipolar process. If there is always ‘self’ (the photographer) and ‘other’ (what is photographed) written into the image, what Ballen tries to achieve is a situation where the other is precisely, though in imagistic code, the self. By these lights, Ballen’s grail comes to be (even more precisely) the otherness of a self projected in and explored through his highly idiosyncratic mise-en-scène.

Roger Ballen, Two men with-barbel, 1999 TP

Ultimately it is a one-off thing. As Ballen is aware there is a kind of fin de siècle morbidity about it, and it is predicated on a precarious sense of loss, a sense, as he puts it, that he belongs to the last generation who will grow up with black and white media.

Nevertheless it gives him a unique and poignant perspective on reality and photographic expression – one that is acknowledged in Vi$$er’s much cited e-mail homage to Ballen:

“When me and Ninja saw your photographs,” Vi$$er wrote, “we decided right there and then to put an end to all the music and art we had been working on up till that point. Immediately, we began working on a new project called DIE ANTWOORD.”

The commendation is well in character of course. But it also makes sense. Even before Die Antwoord began actively collaborating with Ballen, they appropriated not only an aesthetic – the textures and the proto-symbolic iconography which Ballen distilled and transmuted from his own photographic explorations and travels: supercharged details of dissolution and decay, grotesqueries, denizens of the psychic underworld of the platteland, boarding houses and other extremities of experience – but also a liberating sense of the conditionality of experience.

Somewhere in the heady mix, the virtual world of Zef comes into being. It is predicated on an entirely unserious, frequently hilarious and almost always outrageous social commentary and stereotyping of experience, but there is also more to it than that. You can read this particularly in the persona of Ninja. What is obvious is the gestural and narrative reference to the overlapping condition of white trash and gangsta. What is less obvious is a register of expression that invokes the state of possession in which the human consciousness becomes the vessel for impersonal and super-personal forces. He gurns outrageously, yes, but in the extremity of the gurning, he becomes more the locus of Zef than Ninja, so to speak. That is why it works and is not just the worst acting you have ever seen!

It is also Ballen of course – though it is Ballen swallowed whole and regurgitated as the ultimately throwaway pop culture which Die Antwoord inevitably and avowedly is. It borrows and references as shamelessly on the visual level as a DJ does at turntables. Crucially though, there is an identity shift in the post-modern appropriation: where Ballen’s imagery – as Ballen – is all about conjuring up the self, in the post-modern half-life of Die Antwoord, the self is subsumed in the imagery itself.

Roger Ballen, Ninja

A conundrum then and a knot: Ballen as an arch modernist using imagery and light in much the same way as an abstract expressionist uses paint – to access and encode the externalised traceries of the self: in homage, Die Antwoord, moving only on the surface, picking like a virtual magpie from the elements of Ballen’s compositions. A knot that gets double tied in the works in the current exhibition, where Ballen takes Die Antwoord (a composite drawn in part from his sensibility) as the subject matter for his photographs.

I am not about to comment in any detail on the images that result. But there are two that might be worth noting in conclusion.

One of these, called Skelm, and in the presentation view rotated through 90 degrees in an anti-clockwise direction, has the disembodied head of Ninja – in gurning extremis – entering the frame horizontally from the right. Framed with graffiti elements – a kind of barbell shape along with abstract forms and markings – it takes the physiognomy away from the moorings of gravity and, implicitly, personal psychology, and instead reduces the face to the status of another graffiti element.

The second is simply titled Die Antwoord and has Ninja and Vi$$er posed against a wall covered with proto-symbolic graffito markings. Both are masked and covered in virtual (and some real) tattoos to blend almost seamlessly with the hieroglyphic noise of the backdrop.

Thus Ballen – though without malice – closes the circle of appropriation to own the images and the nuances and the textures again.

Roger Ballen,

Shack scene

Die Antwoord will be the supporting act for the Red Hot Chilli Peppers tour in South Africa during February 2013. They rejected an invitation to be support band for Lady Gaga’s tour in South Africa during December 2012. The reason for rejecting this offer was feverishly followed by fans from both sides, and is now well documented in tweeter-sphere.

Roger Ballen/Die Antwoord exhibition will open in Los Angeles during the first quarter of 2013 and will also be on view at Pingyao Photography Festival in China in September 2013.

The exhibition in Cape Town was curated by Heidi Erdmann and Roger Ballen.

© Text Ivor Powell/Heidi Erdmann

© All photographs Roger Ballen

[note]

All photos by Roger Ballen

Glossary:

Die Antwoord – an Afrikaans word meaning “the answer.”

Zef – a South African term that can be likened to “kitsch” or “common”

[/note]