Leviathan 9

April 18, 2013

Mission statement by the editors

April 25, 2013The American film industry has always been fond of portraying war. Since its earliest beginnings, telling the tale of America’s wars has been a Hollywood staple. The depiction of armed conflict on the big screen has helped to define how Americans understand war despite persistent historical inaccuracies. Even as Hollywood romanticism has given way to greater realism in a new generation of war films, the truth of war can be confused with the other manipulated reality presented on screen. Chris Kline considers the evolution of modern American war cinema.

D

D.W. Griffith’s racist epic film Birth of a Nation not only offered a revisionist view of the American Civil War and Jim Crow Reconstruction in the deep South to an enthralled audience, it also revolutionised cinema and transformed Hollywood from a nascent industry into a mainstream dream factory of American popular culture. Ever since, especially in times of conflict, Tinseltown has played a key role in the manufacture and delivery of the narrative mythology of the United States to the collective consciousness of the nation through the big screen. And Hollywood productions are not merely how we channel our constructed vision of America’s story in times of peril to ourselves, they are also a populist reflection of how we understand the world beyond our shores, especially our mortal enemies and our justification for war – our righteous casus belli.

More often than not it is an imperfect view, an abridged and modified version of history, told in a necessarily compact manner determined by the medium itself. And if the cinema has long been a global language with many practitioners, a true international art form, it remains nonetheless from its very inception, in parallel, a quintessentially American looking glass, that neither the advent of the small screen nor the web has diminished in its power to move and sway America’s vision of itself. This is never more true than when America wages war or feels itself threatened.

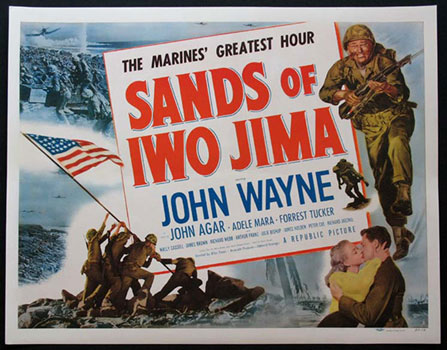

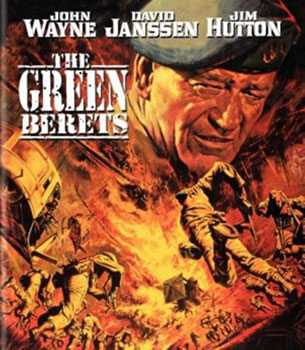

I am friends with a few Marine Corps officers of my generation and I do not know a single one that will deny their emotion when as boys they watched John Wayne sacrifice himself for his fellow Leathernecks in The Sands of Iwo Jima. By the same token, I know some hard-bitten, active-duty Special Forces operators who for all their years of frontline duty still profess veneration for Wayne in The Green Berets.

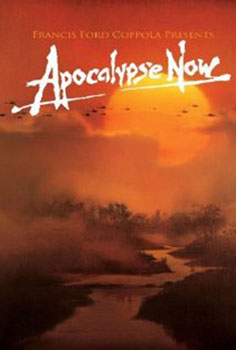

The Duke of course was a screen warrior of a different era, and since the post-Vietnam War period, the trauma and horror of that Southeast-Asian bloodletting infused a new grittiness, a new sincerity and lyricism in American War films that had not existed before, although an earlier generation of visionary directors, most notably Samuel Fuller and Sam Peckinpah, had arguably done much pioneering work to set the stage.

If we consider Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, Stanley Kubrick’s Full-Metal Jacket, Oliver Stone’s Platoon, Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line or Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan we are given masterful portrayals of Vietnam and the Second World that are a universe away from the sanitised depiction of combat and killing, and the facile heroism once as common on screen as the Westerns that depicted evil gunslingers in black hats. The massive grey area of what constitutes moral comportment in warfare, the easy descent into barbarism, the deep psychological wounds, the madness, the nihilism, it is far more apparent, just as the simulated violence has become as gruesome, graphic and vivid as possible.

And since the fiasco of the international mission in Somalia and our recent exit from the quagmire of Iraq, the next generation of screen warfare in the American experience has reached notable high marks with Ridley Scott’s Blackhawk Down and Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker.

In both cases the fly-on-the-wall portrayal of Rangers in Mogadishu firefight hell and the serial recurring nightmare of Explosive Ordnance Disposal work with an elite bomb squad in Iraq provide sympathetic and intimate portrayals of contemporary American soldiers in harm’s way. The latter sharply explores the addiction to conflict, the adrenalin dependency, the danger-juice no war junkie, who learns to love his time toying with mortality, can do without, making the homecoming back to “the world” so alienating and crushingly banal.

As ever the comradeship of war, the visceral intimacy of those who share the fray in the face of death, so incomparable to the other dimensions of the human existence, is also an anchor for both films.

A legitimate criticism is that neither film deeply examines the antagonist. American war films very rarely consider the other side in any depth – psychologically, historically or emotionally (Clint Eastwood’s wrenchingly beautiful Letters from Iwo Jima is a rare case apart). That Iraqis or Americans themselves should have any grievance about the Anglo-American invasion is not broached much by Hollywood, save for Paul Greengrass’ Green Zone, a middling thriller at best that is more Jason Bourne in Iraq than a truly investigative exposé, which nonetheless does treat the skullduggery behind the rush to war over entirely illusory WMDs. In the darker context of Iraq, it took a British film director, Nick Broomfield, to give us the deeply disturbing, documentary-like Battle for Haditha, which examines real-life war crimes committed by US Marines deeply brutalized by the conflict and suffering from extreme combat stress after the loss of their buddies to ambush, that soon leads to atrocity. It is not a film that Americans care to remember much, but it is a strong contribution made all the more credible by using former combat Marines and Iraqi refugees as actors.

Iraq full stop, however, is not a subject we care to discuss as a nation, except that we are glad that we left and we would rather not consider the legitimacy or illegitimacy of our actions there. One of our last images of the war on the small screen was of jubilant, rather naive GI’s in a news broadcast departing by convoy to Kuwait and shouting with pride how they had “liberated Iraq.” From Saddam for sure, but what did we leave in his place? That cry may be a salve on the national soul for the loss of some 5000 GI’s killed in action if it is to be given much weight at all, but it is not an opinion shared by many Iraqis who still endure a monthly death toll of several hundred casualties and have endured to date between 600,000 to 1,000,000, mostly civilian, fatalities since 2003.

And as America’s other long war drags on in the Hindu Kush, arguably the strongest film to emerge thus far of the soldier’s calvary in Afghanistan, is not a fictionalised treatment but the real-life Restrepo by the frontline journalist team of Sebastian Junger and the late Tim Hetherington, an Oscar nominated documentary that tells the tale of American paratroopers in the Korengal valley, some of the most dangerous real estate in all of South Asia. If it is an imperfect film, in purely filmic terms, there is a raw integrity to Restrepo that is undeniable, precisely because it is an unvarnished account of life on the battlefield from the ant’s perspective, from the grunt on the line. Curiously though, it is a film almost devoid of Afghans, though its intention was always to consider the soldier’s perspective. For all of its violence, one seldom sees what happens when metal connects with flesh and bone, but the impact of the fatal result, the losses suffered by the troop we come to know, including its namesake, the jovial medic called Restrepo is clear.

We do not see actors; we see real soldiers and we witness their loss, their fear, their courage, their ennui, their rough soldierly humour, their love for one another, their unpretentious gravitas and their stoicism. The film is all the more poignant for Hetherington’s death in Misrata last year covering the Libyan Revolution. I met Tim a few times. He was a close friend of one my close friends, a fellow journalist. While I did not know him well, I can attest that I know full well how much he is mourned by our profession, and that he was the genuine article in a way that few Hollywood purveyors of violence are. One could hardly imagine Quentin Tarantino sweating out a year-long tour of duty in the Korengal, as Tim did, to capture the truth – a limited one, but an authentic one, nonetheless, which required a soldierly courage. His repeated proximity to the truth of war and his compassion for the “men and women trapped in reality”, as war photographer Robert Capa put it, is exactly what claimed Tim’s life in a place far away from the glitz and self-satisfaction of Hollywood’s A list.

One of Tim’s great, humanistic accolades is that the soldiers of the Korengal mourn him as one of their own. To complete the arc of America’s modern celluloid wars we must gaze upon this year’s Oscar winner Argo and also-ran Oscar contender, Zero Dark Thirty. Purely as movies one would be hard pressed to deny that each in its own vein is a compelling, taut, dramatic journey that captures the viewer’s attention from the start, ably retains it and keep us watching all the way to the satisfying finale, as different as each is. And it is significant, if we also briefly consider the Academy Award-winning Lincoln, that, at a time when America is very much still at war in Afghanistan, quietly ever more engaged in global, largely clandestine struggle against Islamic extremism and bracing itself for the new fault lines of looming conflict to unravel from the Middle East to Southeast Asia, that war and terrorism should have dominated the Oscars. In choosing the man at the helm of the Union during the fratricide of Civil War (still our bloodiest conflict), the Iran hostage crisis and the hunt for Osama Bin Laden, is it that war sells movie tickets, or that Hollywood is itself a barometer of where America keeps venturing in a violent age?

Director Kathryn Bigelow

Ben Affleck’s and George Clooney’s Argo is a bona fide nail-biter, sometimes as funny as it is nerve-wracking. We watch the US Embassy in Teheran being overrun by radical students loyal to Ayatollah Khomeni and Iran’s Islamic Revolution, and then enter the remarkable reality of how six embassy staffers, first sheltered by the Canadian Embassy, escape to safety. In case you haven’t seen it, I shan’t ruin the storyline for you by providing any more detail. But there is much that is missing, if Argo is to serve as a de facto record in the public conscience of our dealings with a decidedly difficult and dangerous Iran. It is just not the whole story. And it is hard to do that in two hours, “it’s only a film after all”, entertainment in the end, not history or scholarship. The problem is that in our culture it will come to mean that it will help to define a historical reality, even if it is glaringly incomplete. And let me be perfectly clear, any embassy is the sovereign territory of that nation and this must remain an inviolate principle or the concept of all embassies is nullified.

What took place in Teheran was an act of war and inexcusable.

But where I diverge is that the takeover of the US embassy is only one of the most despicable pages in the relationship between Iran and the US. What most American filmgoers will not consider is the anger that led to the assault and hostage taking. It is a matter that takes us back to 1953 and the toppling of Iranian Prime Minister Mossadegh in an Anglo-American-orchestrated coup that restored the Shah Reza Pahlavi to power. Mossadegh had the nerve to nationalise US and British petroleum holdings, arguing that Iranian oil profits should go primarily to Iran rather than to multinational corporations.

And then what ensued? In short, the United States Central Intelligence Agency with vital help from the Israeli Mossad, trained the Shah’s brutal secret police the Savak, which then tortured and murdered untold thousands. Despite the Shah’s efforts to modernise and educate his country, these brutal aspects of his rule ultimately lead to his overthrow and the rise of the Ayatollahs, which sadly takes us to the present day and one of the most repressive and intolerant regimes in the whole of the Middle East. Then of course there is the small matter of the Iran-Contra Affair and US weapons bartered for hostages by Ronald Reagan. The gist here is that the tale of good versus evil is a little more convoluted than Hollywood can convey.

Zero Dark Thirty has been chastised sufficiently for allegedly glorifying and justifying the use of torture in obtaining actionable intelligence, and for the production having enjoyed such privileged access to the CIA’s classified records that it constituted a breach of security and resulted in the sort of propaganda not seen since Hollywood was enlisted by the War Department in World War Two.

This has been covered; I cannot verify any such aspersions. I remain a devoted fan of Kathryn Bigelow as an incisive director of intelligent action films and absolutely would have cast a vote for best Actress for Jessica Chastain’s superb performance as Maya, the dogged, fierce and gifted CIA agent who tirelessly spearheads the effort to track down Bin Laden until SEAL Team 6 is deployed to kill or capture him.

Jessica Chastain & Edgar Ramirez arrive at the “Zero Dark Thirty” LA Premiere.

My problem is, again, not so much with the film, given the limitations of the medium or the stated aim of the movie, but rather in the perceptions that will follow and long endure because of it, and equally those which will not be discarded because of it, by a largely under-informed American public. I will not soon forget the sense of horror, shock and then rage that I felt when I witnessed the twin towers collapse on 9/11. The world rallied to us as we correctly moved to strike back against those who attacked us, In short order toppled the Taliban and chased Al Qaida out back across the Pakistani frontier. But we then shortly abandoned Afghanistan, blundered into Iraq on the basis of a lie and helped engender the very thing we intended to contain – terrorism – and in the process we turned Iraq into a charnel house.

Our enemy was in Afghanistan…there were no WMD in Iraq and no linkages to Al Qaida, but we starved the legitimate mission in the Hindu Kush of manpower and resources under the Bush administration, so that the surge overseen by the Obama administration comes too little too late. We have all but lost the war in Afghanistan and when ISAF packs up next year, no doubt the future of Afghanistan and the repercussions of our slow moving failure there will haunt us for a long time to come.

Like any sane person I do not shed tears for a medieval zealot who came to my home to do evil and I have written about that here and in British newspapers. But his death, if not exactly a Pyrrhic victory, comes after a long string of strategic disasters that do not constitute America’s finest hour. It was a brilliant commando raid, it was an epic manhunt, not least also for the vital contribution of brave Muslim Americans. It made for a wonderful film, but Zero Dark Thirty was just a movie and like Argo it does not inform the American public why so much bitter enmity remains in the larger Islamic world venomously directed against the United States and the West as a whole. It also does not inform the American public that the vast portion of the butcher’s bill for the excesses of radical Islamist terror is borne by Muslims who oppose it, not by Americans or Westerners. But we continue to demonise all Muslims, especially in Hollywood. A clear-cut and enduring victory against terrorism is virtually impossible to predict or ensure, whereas the future hardship and likely tragedy that still awaits us is not. If films like Argo and Zero Dark Thirty bolster our resolve, our tenacity to endure and overcome, that is a good thing, but we would do well to remember that we do not win wars in cinemas.