US Congress and Online Piracy – the Ongoing Acronym Saga

April 25, 2013

Polenta. The variety of a dish

April 27, 2013Israel’s Prime Minister Netanyahu has asserted that there is a threat from the “strange union” of Islam and the political Left in the West, particularly in Europe. Nir Boms and Shayan Arya tend to agree. Here they explore what they see as the various historical nexuses of this phenomenon

T

“This is the strangest union you could possibly contemplate,” said Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to CNN’s Piers Morgan describing the alliance between Europe’s radical Left and Islam’s most radical wing. “Radical Muslims”, he continued, “stone women, they execute gays, they are against any human rights, against feminism, against what have you. And the far Left is supposed to be for these things.”

Listening to Prime Minister Netanyahu, one would have thought the union between radical left and radical Islam is a new and worrying phenomenon. However, worrying as it is, new it is not.

More than three decades ago the same “strange union” of the Left and Islamic radicals led to the triumph of the Islamic revolution in Iran which toppled Iran’s monarchy and ended the reign of the late Shah in 1979. This Left-Islamist alliance played a decisive role in the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran by endorsing its founder, Ayatollah Khomeini who, in turn, was quick to decimate the radical Left, its ally at the time.

Although this alliance succeeded in ending the late Shah’s regime in 1979, its roots go back some fifty years, to the formation of the more secular and pro-Western Pahlavi dynasty in Iran. But it took until 1963, a time of reform in Iran, for the camps of Iran’s radical Islamist and radical Left to join hands and form a more tangible alliance that later migrated, with Ayatollah Khomeini, to Europe as well.

Modernisation and its Allies.

View of Charanak, an ancient village in Iran

The year 1963 marked the “White Revolution” in Iran, a process encompassing a number of reforms aimed at modernising the country in a number of key areas, including land reform, education, the status of women and the economy. Although it was not implemented in full, it was a very ambitious undertaking. The programme included: a significant land reform with the aim to abolish Iran’s ancient feudal system; the nationalisation of forests; privatisation and the sale of state-owned enterprises to the private sector; implementation of a profit-sharing plan for industrial workers, and the formation of Literacy Corps, Health Corps and Reconstruction and Development Corps. The Corps aimed to improve the life in villages by eliminating illiteracy in remote villages, extending health care and teaching villagers modern methods and techniques of farming, gardening and keeping livestock. Young university graduates with special skills were allowed to perform two years of their compulsory military service in these corps. The schemes were implemented successfully. The Health Corp, for example, was able to train almost 4,500 medical groups and treat nearly 10 million patients in remote villages and rural areas. As a result of the work of the Reconstruction and Development Corps in thousands of villages, agricultural production between 1964 and 1970 increased by 80% in tonnage and 67% in value.

The White Revolution also granted Iranian women the right to vote, increased women’s minimum legal marriage age to 18, and improved women’s legal rights in divorce and child custody matters. Undoubtedly, the reforms were unprecedented in Iran – but not just there. They were unprecedented in the region and, in some cases, such as women suffrage in 1963, it was even ahead of developed countries like Switzerland, which gave women the right to vote in early 1970s, nearly a decade later.

While much can be said about the strategy used to implement these ideas, which, due to their scope, naturally were not devoid of problems and mistakes, it is important to understand why and how Iran’s Left had ended up joining the opposition to this attempt at modernisation.

These reforms were opposed by some of Iran’s clergy on the grounds of their un-Islamic nature. Ayatollah Khomeini led the resistance and initiated an uprising on June 5, 1963. In the course of the clashes, the authorities quelled resistance among the religious students in a seminary in the city of Qum, and a number of students lost their lives. Khomeini’s activities eventually led to his exile to Iraq in 1964. But while his opposition might be easier to grasp – after all, Khomeini was an Islamist who firmly stood against any attempt to veer away from Islamic doctrines as well as pro-Western agendas – it does not yet explain how it brought the three seemingly opposing camps, the religious Right, liberal Left and the radical Left together under one aegis.

Northern area of Tehran

It’s the land, stupid

Looking at some of the reforms implemented between 1963 and 1978, one might encounter difficulties finding the reasons behind the opposition to them, in particular the opposition of the Left. To understand this phenomenon we should further analyse the interpretation and perception of the White Revolution by the Left and the liberals in Iran and, later, outside of it.

Ironically, the trigger for this “strange” alliance was the Land Reforms Programme which aimed to eradicate feudalism. Under this mandate the government bought land from the feudal landlords at what was considered to be a fair market price. The government later sold the same land to the peasants who had worked the land for generations at 30% below the market value, with government loans payable over twenty-five years at very low interest rates. This scheme made it possible for millions of peasant families – who, till then, had been slaves of feudal overlords in all but name – to own the lands they had been cultivating for generations. The land reforms programme brought freedom and relative prosperity to millions of peasants and resulted in a surge of popularity for the late Shah.

Radical Muslims were set against it for a number of reasons. To begin with, the Mullahs were collectively one of the largest land owners in Iran and naturally did not like the idea of distributing their ill-gotten lands to the peasants. Further, the very notion of a secular government and monarch gaining popularity among their core constituents – the very poor, yet conservative and religiously pious peasants – made them very uncomfortable, to say the least. Finally they did not like the idea that the land reform would also weaken one of their most important allies and financial backers: the feudal families who were, and had been for centuries, an important ally, as well as source of revenue and support for the clerical establishment.

Shepherd with a donkey. Iran

These considerations put the Mullahs in a very precarious position. On the one hand, they could not directly oppose the land reform without losing face and being accused by the masses of looking after their own financial self-interest or those of their fabulously rich feudal backers. On the other hand, they could not risk losing their financial and political base. The clerical establishment struggled to come up with a logical argument against it and used every excuse they could find, from Sharia Law to the possible damage it would do to the agricultural output of the country.

The National Front, a group of liberal Left or Social Democrats, was likewise opposed to these moves. The group, created by former Iranian Prime Minister Dr. Mossadegh, opposed the existing Western domination and control of Iran’s natural resources. In 1953, Dr. Mossadegh enacted the Oil Nationalisation Act, which immediately led to the loss of nearly all British and American oil income and, in turn, to a military coup attempt that was facilitated by the CIA and MI6.

Khomeini on 2000 Rials banknote

National Front members were still bitter about the 1953 events that removed their hero’s government from power and for which they never forgave the late Shah. They too, like the Mullahs, had very close ties to the feudal establishment. Some of their leaders, such as Karim Sanjabi, were feudal lords themselves with vast land holdings. Mossadegh himself was from an aristocratic princely feudal family and his uncle, Prince Farmanfarma, was arguably the most influential feudal lord of his time. The National Front was also faced with the same dilemma as the Mullahs: how to oppose the White Revolution without losing face and looking hypocritical? The far Left was in a similar pinch. This camp included various communist groups, the largest of which was the “Tudeh” party, a staunchly pro-Soviet group and the oldest such group among them. As communists, they could not defend the feudal system, yet they resented the idea of it being abolished by the Shah who would thereby be gaining popularity among one of their largest potential bases, the peasantry.

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi,

the last Shah

Another troubling aspect concerning the White Revolution reforms dealt with two particular programmes concerning workers rights, another perceived agenda of Left. The first was profit-sharing for industrial workers in private sector enterprises. This scheme gave factory workers and employees a 20% share of the net profits of the places where they worked. The second scheme gave workers the right to own shares in the industrial complexes where they worked. This was done by turning industrial units, with five years’ history and over, into public companies, where 49% of the shares of the private companies would be offered for sale to the workers of the establishment at first and then to the general public. This idea, unprecedented at the time, became more acceptable some 30 years later when entrepreneurs such as Bill Gates of Microsoft made stock options a common household concept, demonstrating that shared ownership is actually good for business.

It is no surprise that the Left struggled to come up with a logical response and a practical way of opposing the reforms without losing face with the masses. Profit sharing and stock shares, in addition to the land reform, were most worrying to the radical Left. If those schemes were successful, they would undermine the Left’s standing with two of their main potential bases: peasants and industrial workers.

The radical Left’s response to these principles fluctuated between supporting aspects of the White Revolution but attacking its implementation, to totally dismissing it while branding it an American imposed half-measure reform programme, intended to fool the masses and weaken the country. Other criticism of the Shah’s tight hand on internal security and censorship regime helped bolster the case.

Observing these dynamics, the politically savvy Khomeini, a middle-ranking rising star in the clerical circles at the time, came up with a solution to the dilemma of the Left. He advised the clerical establishment and, indirectly, others that it was to their political advantage to oppose the White Revolution on constitutional bases. The late Shah had passed the principles of his White Revolution in a popular national referendum conducted in 1963. There was some controversy surrounding the result but Khomeini came up with another compelling argument: since there was no provision in 1906 Iranian constitution for referendums as a mean of passing new laws, he dubbed the entire move as unconstitutional.

Khomeini was partially correct in his argument since the 1906 Iranian constitution did not touch upon the issue of referendums. But that was beside the point. Khomeini’s line of argument offered a golden path that allowed an opposition to the Shah and his popular reforms without being against the idea of these moves, which were perceived to be popular with large segments of Iranian society.

Khomeini’s suggestion sat well with the National Front and the Left. Gradually, in a sort of unwritten consensus, they gravitated towards a narrative that worked for them all: calling the White Revolution an unconstitutional half-hearted reform imposed on Iran by the Kennedy administration. This narrative allowed them to attack the whole idea of the White Revolution as well as damaging the Shah’s credibility and intentions, without opposing the principles of reforms and risking the alienation of those who benefited from them. The alliance between the three seemingly opposing camps strengthened over time, enabling Khomeini to gain political influence both within and outside of Iran.

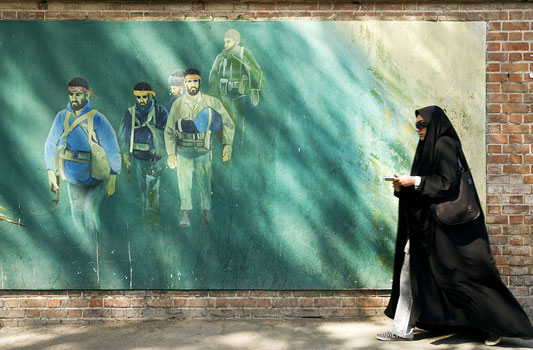

Tehran street mural

An Alliance is born

In Europe as well as in America, the Left had long had a weakness for revolutionary regimes. This is why philosophers such as Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, and Michel Foucault, as well as many lesser-known personalities, were leaders and active members of what can only be characterised as Khomeini’s support committee in Europe.

The Socialist Party, led by François Mitterrand, proclaimed its “resolute support” of the movement. The French Socialist Party organised a public demonstration of support and its executive office saluted the victory of the Islamic revolution on February 14, 1979 calling it “a popular movement of an exceptional dimension in contemporary history.”

Sartre, Foucault and many other left-leaning intellectuals had a relentless hatred of bourgeois society and culture, combined with a spontaneous sympathy for groups at the margins. This seems to be at the core of their behaviour towards Islamic radicals. How else can one explain the behaviour of esteemed intellectuals such as Michel Foucault – openly gay and an apologist for sadomasochistic sexual behaviour – becoming the most enthusiastic supporters of the radically conservative Islamic revolution in Iran?

And France was not alone. Danish historian and former Trotskyite, Torben Hansen – another eyewitness to the Iranian Revolution – wrote in articles for The Class Struggle about Khomeini’s Islamic “Persian philosophy of rebellion.” Hansen, who eventually changed his views, was so convinced of Khomeini’s path that he joined Gert Petersen, the leader of the Danish Socialist People’s Party in a demonstration in front of the US Embassy calling “marg bar – Amrika” or “Death to America” in Persian .

In America too, people like Professor Richard Falk, Andrew Young and Senator Edward Kennedy, as well other influential liberals, became vocal supporters or sympathisers of the Islamic revolution.

The Shah’s Mosque in Isfahan, Iran

Another Strange Union

The late Shah and Israel are, in some respects, similar. For totally different reasons, they attract the wrath of Islamic radicals and the Left simultaneously. The radical Muslims hated the Shah due to his secular policies and Western outlooks that undermined the traditional religious establishment and values they had promoted for 1400 years. The radical Left hated him since he symbolised bourgeois society and because of his staunch pro-western outlook and his alliance with America. Both, radical Leftists and Islamists alike, wanted to see an end to the Western influence in Iran and viewed the Shah as the main obstacle to their grand plans. Since, for both groups, destruction of bourgeois society and ending the West’s influence was the main priority, an alliance was a natural progression.

In similar ways, the European radicals and radical Muslims have similar regional goals in the Middle East. Both groups share isolationist tendencies stemming from their reaction to European colonialism, although for different reasons. Radical Muslims are in conflict with Western values and perceive a threat in Western influence while the Left wants to distance itself from anything remotely resembling its colonial past. As a result they both want to see an end to Western intervention in general and America’s involvement in particular with the Middle East. Ironically, both see Israel as one the main instigators of such influence, as well as the main obstacle to its end.

In addition to the anti-colonial sentiments, values also play a role when it comes to the radical Left. Moral relativists hold the view that ethical and moral standards are relative to what a particular society or culture believes to be good or bad. It is ironic to note that, unlike the radical Left, for whom relativism has become part of their political discourse and character, for radical Muslims there is no illusion as to the superiority of Islamic morals and culture.

Karl Marx famously said “History repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce.” What happened in Iran during the Islamic revolution and what ensued as a result of the strange union between the radical Left and radical Islam was truly a tragedy and one that should not turn once again into a farce. An Old Persian proverb reminds us that “the past is the lantern that illuminates the path to the future.” Let us hope the European Left will learn a thing or two from Iran – if not for everyone else’s sake, then at least for their own.

[note]

Dr. Nir Boms is a co-founder of CyberDissidents.org. Shayan Arya is an Iranian activist and a member of the Constitutionalist Party of Iran (Liberal Democrat).[/note]