Mission statement by the editors

May 28, 2013

Leviathan 10

June 1, 2013The extraordinary nature of the events in the Vatican in the weeks leading up to Easter celebrations cannot be understated. For the first time in over seven hundred years a pope voluntarily resigned his office. Still, it is unclear what these events will ultimately mean for the church. The new pope, Francis I, is very different from his predecessor – but is that difference in substance, or merely in style?

R

Rome, 13 March, 2013. It is a few minutes after seven o’clock; the weather is cold, rainy and miserable, but the huge space that covers the front of the Vatican Palaces is packed with multicolour rain jackets and umbrellas. Since the beginning of the month, when the Sede Vacante was declared, there has been a perpetual small crowd stationed outside the Papal residences. But today the air is electric. Only yesterday morning the one hundred and fifteen cardinals entered the conclave, yet there is unrest among people in the square, because the announced evening voting session is running late. That can only mean one thing. No wonder a roar of happiness welcomes the white smoke when it emerges from the Sistine Chapel’s famous chimney and climbs towards the dark skies. St Peter’s bells toll joyfully through the air. Habemus Papam, the old formula that has consecrated so many before, will soon be spelled out again in St Peter’s Square. It’s not long before the Papal Swiss Guards, with shining medieval helmets and silky pastel colour uniforms, draw up in formation to present the new Pope with the guard of honour. The event marks the beginning of the strict protocol that leads, a few minutes later, to the opening of the well-known balcony at the top of St Peter’s Basilica. There the new pontiff is announced.

For a moment the crowd is silent. Not many recognise the name of Cardinal Bergoglio. Even more surprising, no pope in the past has dared to use the name he has chosen: Francis. Keeping the picture in accordance with the name of the famous saint, the champion of the poor, when the new pope shows up he does not wear the red velvet regalia of the Bishop of Rome. He looks happy, cheerful and strangely simple. He speaks with a breaking voice and an enjoyable Argentine accent when he addresses the crowd in Italian. He never mentions the word “pope,” not even once. This is a rare event, but the historical moment is even more unique: not so many times in the nearly two millenia of history of the Roman Church have there been two living popes – at least, two popes who are not fighting for the same role. That is something new.

But let’s start from the beginning. On the night of the 15th of February an extraordinary thunderbolt hit the highest peak of Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome. This was actually the second lightning bolt of that day. Just hours earlier, in a move that took most of the world by surprise, Pope Benedict XVI read a brief declaration and stepped down from the role of Pontiff and Highest Shepherd of Catholicism.

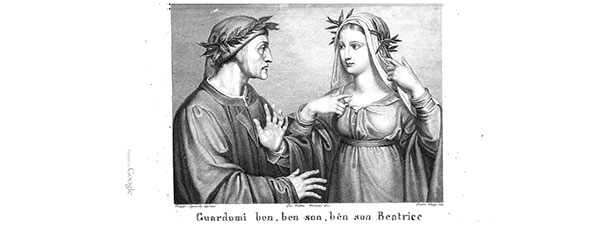

The event of a pope voluntarily leaving office was almost unthinkable up to that moment. John Paul II’s long agony prior to his death was still fresh in the memories of many. Celestine V, a famous medieval eremite, took a similar step in 1294, to escape the curial court’s intrigues and battles and caused outrage during those years of unrest. Although the papal state was considered rogue by many and was the arena for power struggles among influential Roman families, Celestine’s gesture caused a genuine scandal – such a scandal, in fact, Dante, our famous Poet, reserved a very bad place for Celestine V, placing him in the anti-Inferno, and, in so doing, keeping his memory alive.

Pope Ratzinger will hardly find a place in any contemporary work of art, unless you put Dan Brown’s novels on the same shelf as Dante’s Comedy. However, his decision took many by surprise. In a world with fewer and fewer points of certitude, the Pope and the Church have been among the most unchangeable and immutable, able to survive waves of revolutions, secularisation and scandals. For the first time in history images of the pope emeritus leaving office by helicopter among Swiss Guards on parade and servants in tears filled worldwide news, but left many questions on the table.

In particular, the real reasons behind Ratzinger’s decision have yet to be understood. Officially, he left office because, he said, his strength had deteriorated to the point that he had “to recognise the incapacity to adequately fulfill the ministry” he was entrusted with. The question was: did incapacity mean the Pope’s old age or that he lacked the strength to fight battles yet to be engaged, in full? It is not a mystery that the Holy See is deeply divided at its highest levels, but was Ratzinger’s choice a last resort in a battle he was on the verge of losing?

The series of important documents stolen from the Pope’s apartment, known as “Vatileaks”, revealed that, even though hidden behind thick layers of red muslin and velvet, the Pope was being in some ways overwhelmed by various factions fighting for power within the Vatican walls. The documents showed that the Church, again, concentrated more on maintaining itself institutionally and its balance of power around the world than anything else. This was thrown into particularly painful relief by the latest revelations on priest paedophile cases, this time in Italy and Scotland. For the “well-being of the Holy Roman Church” and for its “honour”, serious abuses had been quietly buried in bureaucracy and negligence.

The impression is that Ratzinger could not face all of that anymore; the powers he carefully managed to keep at bay during his reign were escaping the net, out of control. The risk of a chaos ensuing for the overall government of the Church was too big a gamble to take. Hence, the historical decision to step down.

The conclave locked its doors in the face of many issues. Unrest could be read on the faces of the old cardinals, lined up in St Peter’s to attend the Pro Eligendo Mass. The compromise they found is, given the state of things, quite stunning. For the first time, a cardinal from the Americas was chosen, a candidate far-removed from the intrigues of Rome, from the strong powers of the Italian and European congregations. Already, just a few days from his election, Francis shows a disconcerting energy and practicality, that has taken many traditionalists by surprise. He speaks frankly, does not like technicalities and protocols, and possesses a style that is easily comparable to that of John XXIII, the Pope of the Second Vatican Council, who was a reformist and a man far from intrigues and close to the people, according to the common understanding.

Ultimately, that may not be the case. The conclave included, for the most part, cardinals promoted by Benedict XVI, and none of them is reformist in the strict sense. It is true hard-core radicals were a minority, but there was no doubt the expression of this conclave would be traditionalist. In fact, Ratzinger was a reactionary himself, former Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith – previously known as The Inquisition. He managed to put in the mix some slow changes, but paramount to his papacy was his aim to restore the traditional role of the Church in society. He never managed to change the view of himself as a man of the establishment, following the path mapped out by his predecessor and far from open to major reforms.

Pope Bergoglio, instead, seems to have taken office in a spirit of innovation, eschewing protocol, rigid speeches and fake smiles. However, his opinions on gay marriage and the role of women in society have raised more than one brow in the past, thanks to uncompromising declarations released to the Argentine press as the cardinal he then was.

Some commentators have mentioned the possible role he played during the Videla dictatorship in Argentina in the infamous Dirty War of the late 1970s and early 1980s. While reprehensible if true, nonetheless, the Church has often taken officially accommodating positions towards crude regimes, either to better defend its position in the society or to gain a more favourable one.

Bergoglio comes from Jesuit ranks, and rumours abound that the religious order’s powers extend a little bit too far within the Catholic universe. Francis’ papacy will almost certainly increase them dramatically. In any case, Pope Francis’ attitude has generated more positive than negative comments. So far it looks like an innovative change for those who want to see a sign of change of direction at the top of the Holy See.

Such change of direction has happened rarely in the history of the Church. Acceptance of new concepts is a rare quality within institutions governed by dogmatic laws; change can occur, but it develops slowly. In fact, it is not only Cardinal Bergoglio’s election that allows one to look forward to new and surprising twists. Innovation has always seemed to spring from the very ranks of the Soldiers of God, the Jesuits themselves. An eminent Jesuit, Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini, one of the late Italian prelates seen as ‘papabile’ (possible candidate for Pope), although keeping a firm hand on the core creed, set a palpable innovation just months before Pope Ratzinger’s renunciation. Before he died in August 2012, Cardinal Martini gave an interview – published posthumously in the Italian newspaper Il Corriere della Sera – where he addressed some core concepts of the Church, branding them old and antiquated, lagging “200 years behind” the times. Analysing the state of Catholicism, Martini went so far as to argue for a manifold reform process as the only way for the Church to avoid becoming a box with no content.

The Church needs a real conversion, he argued. A full and thorough renunciation of the mistakes made is needed, a radical alternative strategy to address the paedophile scandals and demands for updated views, particularly in response to the question “Do people still follow Church’s suggestions on sexuality?” Moreover, the Church needed an alternative view of catechism. Martini recalled that the Second Vatican Council “gave back the Bible to the people”, dramatically reducing the distance between altar and observant. Neither the clergy, nor the canon law could replace human self-analysis and inner reflection. “External rules,” he went on, “are coded to answer internal thoughts”; to be part of the Church, a person must interiorise the word of God, not the other way round. Thus, the traditional rites and their relationship to the everyday catholic church-goer must be updated as well. Specifically, Cardinal Martini struggled with the idea of the “enlarged family”, divorced parents and children with no family in traditional terms. Is there a way, he argued, not to alienate them, given that a large number of non-traditional families are observant?

A new papal election historically raises hopes and dreams, and Pope Francis’ case is no different. Nevertheless, in an era where even the reactionary Ratzinger used Twitter, the pope who comes “from the end of the world” offers an interesting perspective for the observer. One would hope Francis shares the ideas of his Jesuit brother Cardinal Martini, but the answer is probably as many-faceted as the question. A Church deep in obscure rituals, wealth, and striking such a marked separation from the everyday person is probably so outdated that no pope can allow himself to sit still and see Vatican institutions tumble, spiritually and politically.

Easter celebrations have strangely seen Pope Francis setting the pace at an unusual speed. The traditional feet-washing ceremony, normally flamboyant and reserved only to males and prelates, has been held in a gaol, where Francis washed the feet of male and female inmates alike. A few days later, he talks about the “primary and fundamental” role that women play in society. Is this a real change on the horizon? Is this just so much smoke and mirrors or is the new pope a genuine innovator?

The tale of the new pope from the Americas is yet to be written. Nonetheless, Benedict XVI’s decision has opened up a completely new era for the Church, if only by allowing our century to witness the unique situation of having two living, non-feuding popes. The last time it happened, it laid the basis for Protestantism. The question still stands: could it also lead to a new revolution this time?