The Great World in Miniature: An Introduction

June 1, 2013

The Symbiosis of Artist and Viewer: François Ozon’s Dans la Maison

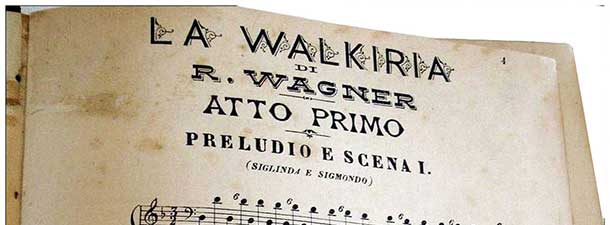

June 1, 2013Richard Wagner is a towering and controversial figure in the history of opera. Even now, two hundred years after his birth (which coincides with Verdi’s bicentenary) Wagner caused quite a stir when the leading Italian opera house – the world-renowned Teatro alla Scala in Milan – chose to open its season with a Wagner opera instead of with an opera by Verdi, even though it was Verdi who had had a special relationship with La Scala during Verdi’s lifetime

E

Everything Richard Wagner did was characterised by the huge scope and ambition of his vision. Photographs show a well-dressed man in a velvet beret whose calm, stately expression is that of a prominent figure among composers. No detail of his life was too banal to be aired in public (for example, his taste for silk underwear). This fascination would not have been possible without the sheer power of his music and the ambitious claims he made for opera. This art form is perhaps the most bizarre ever to receive and achieve widespread popularity. The extreme reactions to any mention of Wagner, however, are not limited to opera-goers. His impact on modern thought has been considerable. Students of history, politics, psychology and literature, as well as musicians and artists have had much to say, but anyone with an interest in almost any intellectual aspect of the modern world needs to come to terms with Wagner.

Richard Wagner

Picture from Meyers Lexicon books

His works marked a return to the spirit of court operas of the seventeenth century as a festive and spectacular event. He grappled with the most universal themes of human behaviour yet rarely settled on easy answers or comforting morality. He wrote his own librettos and hence was responsible for both the sound of the music and the message in the words of his operas. His crusades against running opera as a business enterprise and against the decline of German culture diminish in contrast to the impact of his music and its daring modernity. His influence on the development of opera and instrumental music is immense. He was ambivalent about the virtues of capitalism as opposed to a communal form of economics. He found in German myth and contemporary philosophers a justification for the German race being regarded as superior to all others. He was anti-Semitic yet selected Herman Levi, a Jew, to conduct the first performance of Parsifal, the most Christian of Wagner’s operas. Women in his works frequently embody virtues and wisdom that his short-sighted men lack; in real life he revered most of the women he encountered.

Though he anticipated and helped shape our modern world, Wagner was very much a man of his time. He was a political revolutionary who fled from the police in Dresden and spent twelve years in exile. He found himself constantly in debt and had to appeal to wealthy patrons to support him. In later life, he was fortunate to have King Ludwig II of Bavaria sponsor and support him lavishly. Ludwig had ascended the Bavarian throne as an 18-year old youth. He was a recluse with strange ideas but he became obsessed with Wagner’s music. Ludwig sent messengers to locate Wagner and then proceeded to overwhelm him with gifts and pay off his debts. However, the relationship was a tempestuous one, fraught with problems and disagreements. The Bavarian government disapproved of Ludwig’s financial excesses and it eventually succeeded in having Ludwig confined to the castle Berg on the shores of Lake Starnberg, where he drowned under mysterious circumstances. Yet, arguably, despite the dramatic nature of the relationship, without Ludwig and his support, Wagner’s later career might not have been possible.

Wagner began composing operas in the 1830s. His first works, Die Feen (1833) in the German Romantic style, and Das Liebesverbot (1834) an Italian-style comedy, were the forerunners of his later, more complex compositions. His breakthrough finally came with the success in Dresden of Rienzi (1840), a grand opera in the French style. The beginning of his distinctive style and his break with provincialism began with Der Fliegende Holländer (1843).

During a trip from Riga to London in 1839, Wagner encountered rough storms in the North Sea which influenced both the music and libretto for Der Fliegende Holländer. To this day, it contains some of the most descriptive music created to depict the power of the sea. The opera deals with salvation of a doomed man who is saved by the love, devotion and sacrifice of a woman. Its success brought Wagner widespread fame and prestige, resulting inter alia in his appointment as Kapellmeister to the Court of Dresden, where he was engaged from 1843 to 1849. This was his most productive and creative period, enabling him to compose Tannhäuser (1845) and Lohengrin (1850), two of the most lyrical operas in the repertoire. During this time he started to reduce the dominance of arias, using instead the arioso form with extended musical passages. Additionally, greater use was made of the chorus which served not only to comment, but also to play an active role in his operas. These creations marked the last Wagner did in the German Romantic style before he developed his own distinctive format.

Statue of Richard Wagner.

“Giardini Biennale”. Venice Italy

Throughout 1848, Europe experienced wide-ranging upheavals involving the formation and expansion of nations, coupled with the rise of capitalism. Wagner became involved in the Dresden uprising and was forced to flee to sanctuary in Switzerland. There he identified a wealthy patron who enabled him begin writing the libretto for an epic dramatic music cycle, Der Ring des Nibelungen. The huge and complex scale of its composition would occupy him during the next 28 years.

The Ring Cycle is a mammoth “work”, comprising a preliminary evening, Das Rheingold, followed by three operas: Die Walküre, Siegfried, and Gotterdämmerung. It is the longest “work” in Western music and is intended to be seen on four consecutive evenings. Current practice is to spread performances over six evenings, due to their length and the demands placed on singers, the orchestra, and the audience. The operas, totalling over fourteen hours, deal with a German romantic view of Norse myths, influenced by Greek tragedy and a Zen sense of destiny. The complex saga unfolds as a master plan for a new approach to music and theatre. It was performed in its entirety for the first time at the initial Bayreuth Festival in 1876.

One of Wagner’s major achievements was the conceptualisation of the Bayreuth Festival Theatre to stage his operas under ideal conditions. The theatre was designed and constructed to his specific requirements, the auditorium being in the shape of an amphitheatre, as opposed to the traditional horseshoe design with its tiers of boxes; the orchestra pit is sunken below the stage, being partially covered. The resulting acoustic ambiance and sound for both the demands on singers and orchestra, and the enjoyment of the audience are regarded as unique, making the annual Wagner Festival a magnet for opera enthusiasts worldwide.

Opera-house Bayreuth, Germany

After several changes of direction and more study on Wagner’s part, The Ring progressed toward completion, and parts were performed in Munich and other towns. The rights to the work were sold and/or given to honour the patronage of King Ludwig; Wagner’s determination finally saw the fulfilment of his dream aided in no small way by Bayreuth when it was chosen as the permanent location for this project and when it gave its financial support and the generous gift of land. He offered patrons the opportunity to donate funds to assist the project and he undertook gruelling tours to London, New York and numerous European cities in order to perform fund-raising concerts. He was an outstanding performer and producer of his own works as well of those of Gluck, Mozart and Beethoven, which influenced and inspired a generation of conductors.

Wagner’s greatest musical hero was Beethoven as a composer of symphonies. Wagner emulated him in parts of Lohengrin, going on to develop a large scale symphonic style as he commenced composition of the Ring Cycle. His most radical work, Tristan und Isolde (1857), written while he was occupied with the composition of The Ring, is based on a medieval tale depicting existential love and eternal death. The music is explicitly erotic with its daring harmonies and expansive musical syntax. Wagner thereafter returned to more humanistic themes such as the popularity of art and the principles of nationhood, as seen in Die Meistersinger Von Nürnberg (1867) and the conquering of sensuality by a moral code in Parsifal (1882).

Jean Paul Square in Bayreuth.

Born in Leipzig in 1813, Wagner’s paternity has never been resolved. When he was a few months old, his father died and his mother married his father’s best friend, who it is speculated might have been his real father. His childhood years were spent in Dresden and Leipzig. At age 20 he became chorus master at the Würzburg Theatre, where in 1836 he married actress Minna Planer. This was never a happy marriage due to their temperamental incompatibility: Wagner was focused on his work, while Minna was interested in domesticity. They both had casual affairs with other people as they wandered Europe in search of fulfilment. They separated in 1862, never to see each other again. She died in 1866.

In Paris in 1853, Wagner had met Cosima Liszt, the illegitimate daughter of piano virtuoso, Franz Liszt and the French Comtesse d’Agoult. Franz Liszt became a major champion of Wagner’s music. Cosima grew up in the Paris of Berlioz, Hugo, Balzac and Chopin and she married Hans von Bülow in 1857. In 1865 Wagner’s opera Tristan und Isolde was performed in Munich, conducted by Von Bülow. Wagner started an affair with Von Bülow’s wife Cosima, who would bear Wagner three children before they finally married in 1870. At age 31, she abandoned her husband and children to share the future and fate of one of the most notorious geniuses of the Romantic Era. During their fourteen years together, they shared the completion of The Ring, as well as the composition of Wagner’s final masterpiece, Parsifal.

After Wagner’s death, Cosima reigned supreme at the Bayreuth Festival. She kept a daily diary until the day of his death and this is one of the greatest sources regarding his later life. Cosima was to become a great influence during his lifetime, giving him much encouragement and running his affairs.

After the performances of Parsifal, Wagner and his family went south to escape the cold and damp weather and seeking relief from his ill health and pains. He moved to Venice for a period of recovery after the extreme pressure of organising Bayreuth’s first Festival, followed by composition of Parsifal. The family took apartments at the Palace Vendramin Calergi on the Grand Canal, a sumptuous residence where they occupied eighteen rooms on the second floor. It was hoped that he would recover some of his strength here, but it is here that Wagner died in 1883.

His body was taken by gondola up the Grand Canal to the railway station and thence by rail to Bayreuth where he was buried in the grounds of Wahnfried. His death left a great void in the opera world. Wagner cast such a shadow over German musical life as a whole that it took decades for any perspective to be regained. Today, the Wagner mystique and myth, along with his unequalled works, thrive through more than 130 Wagner Societies around the world. The annual Bayreuth Festival continues to beckon as a mecca for his followers. In this bicentennial year of his birth, celebrations through performances of his famed Ring Cycle at opera houses all over the world, stand testimony to the legend that is Wagner and the unique inventiveness of his operas. They continue to enrich life for generations of music lovers.

Herbert Glockner is the president of The Wagner Society of South Africa, Cape Town.