Leviathan 12

October 1, 2013

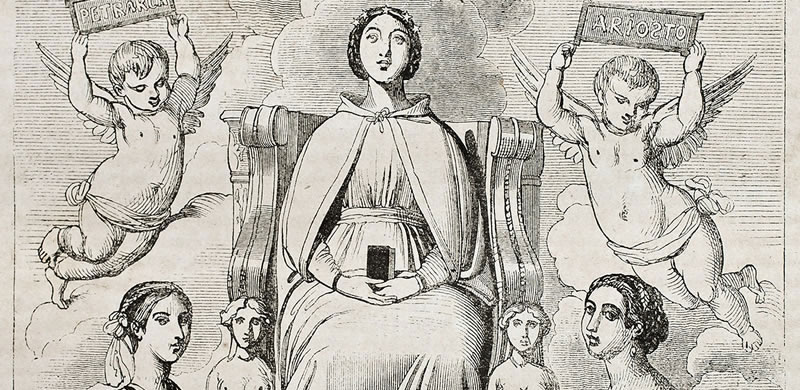

The Divine Comedy

October 1, 2013Sometime around the year 1274, when he was nine years old and she about eight, Dante Alighieri saw Beatrice Portinari for the very first time. Though he did not speak to her, then or after, he immediately fell deeply in love with her. He did not see her again until nine years later, when she was seventeen. They met in the street, she was accompanied by two older women. She greeted him and then she and her companions passed by. Dante was so overcome by her salutation that he retreated to his room to ponder the encounter. There he slept, fell into a dream, and emerged with the first sonnet in La Vita Nuova. Dante, in legend, only encountered Beatrice this couple of times. She died at the age of 24. She would become his muse and the centre of some of his works, including his greatest, The Divine Comedy. If, in fact, Beatrice Portinari was the real-life model for the Beatrice of Dante’s works (most scholars now agree she probably was – though there are doubters) then he knew almost nothing of her real character or of who she herself was, as a flesh-and-blood human being.

This left him free, of course, to place her at the centre of his poems of courtly love, with their romanticised conventions and stylisations and also to invoke her as his guide in the heavens in the grand allegories of the Divine Comedy. He could project all that was good upon her, fulfil an idealised vision of a woman embodying the very qualities of the perfect, the good and the beautiful. He did so with such effect that he created some of the greatest works in world literature. In his ‘relationship’ with Beatrice, however, he never had to confront a bad mood, moments of melancholy, headaches, frustrations, exhaustion at the end of a long day, demands, needs, contradictory opinions, hormonal surges, the occasional inopportune breaking of wind. His – and therefore our – image of her is never tarnished by anything so mundane. There is no shadow in Dante’s depiction of Beatrice.

But what might Beatrice herself say if she were allowed to speak for herself beyond that one brief, late-adolescent greeting on the street? What if she were allowed her voice and thereby the full expression of her own humanity? We’ll never know, of course, and there are those who will say it doesn’t matter. Dante said it all for her, and it was incontestably a glorious addition to our culture. It seems in some ways that we have not moved out of this state of male-female relations since the medieval days of Dante and Beatrice. Men project all that is good within themselves onto women

‘What I expect from you is that you listen. Stand still and let your feet settle into the Earth. Listen. I will tell you what my lived experience is. I will live in my own flesh, and I will do so without your leave. Just exactly as you do in your flesh.

‘I have come to this place in history at great cost and with great struggle. I can go no further until you begin to bear your part of the burden. Stop; breathe; let your heart slow down. Pull in your projections. See who I am. I am neither dream, nor vision, nor hallucination, nor a vessel of your dark desires.

‘And then do your own work.’

‘Your work is to do what the men in Tahrir Square did in Egypt when they stood in a ring around their sisters to protect them from the gangs of men who would rape them. Rather than send women into confinement for their own ‘protection’, they stood and said, no! These are our fellow human beings. We will no longer countenance your violence against them or protect you in it.

‘Do what male journalists in India have begun to do – to put their names and faces online in a viral protest, posing with placards decrying the epidemic of gang rapes in their country and protesting at the lack of investigation and punishment of the perpetrators.

‘Do it not because, as the American president put it, women are ‘your’ sisters, ‘your’ wives, ‘your’ daughters, ‘your’ mothers. Do it because they are human beings. You owe it to them simply on those terms, and on those simple terms they deserve it.’

In this issue of Dante, dedicated to Beatrice, we hope you, our readers, will stop and listen, and begin to hear her voice.

Dante & Beatrice