The Importance of Taking an Italian Brand Globally

March 14, 2014

Asia Smitten With Neoliberalism? Or Struck Down With It?

March 22, 2014Beauty versus practicality, in design terms, is the perennial struggle that is at the heart of every design challenge and none more so than in the cut-throat world of Formula One. Jordan Wilkins for Dantemag retraces the changing styles and fashions behind the successes and failures of this highly competitive and inventive modern phenomenon.

Formula One design is something unique and specific in the world of international motor racing and a discipline that has radically changed from how it began in 1950 up until the present day. Many would argue, however, that since the 1970s, Formula One design is constantly being diluted by the increasing influence that aerodynamics holds over the sport. As the teams have become more serious and competitive amongst each other, this has led to a relentless pursuit of on-track performance, paving the way for aerodynamics to be the sole contributor to F1, diminishing design to the point of being almost non-existent in the most recent examples. This shift between the balance of forces controlling F1 design is the reason for the significant sea-change between how Formula One cars looked in the 1950s and 1960s, compared to the modern era of the 21st century.

A timeline of F1 design begins back in 1950 when Formula One was first created. Throughout that first decade the cars evolved from front engine brutes packaged around svelte bodywork, to low slung insects, by comparison. Many people suggest that the Maserati 250F, designed in 1954, was not just the best looking car of its decade, but of the entire history of F1 with its curvaceous bodywork finished in the iconic bright red paint of Italy’s national racing colours. Adding to the alluring mix of appearance and performance were the long exhaust pipes running alongside the bodywork, making it look as if it was not industrially-machined but hand-sculpted. Finally the evocative Borrani stainless steel wire wheels completed the look of a car that has come to define the excellence of Italian design, which in terms of Formula One during the 1950s, arguably had no equal.

The first major shift in F1 design began in 1959 when the British Cooper team started to gain success with their unique Cooper T51, which was the first car to place the engine behind the driver. Whilst the reasoning for this was purely performance-related it also completely altered the nature of F1 design, as their success swiftly prompted other teams to adopt this philosophy, with every F1 car on the grid being rear-engined by 1961.The future of Formula One design now centred on lower profile cars.

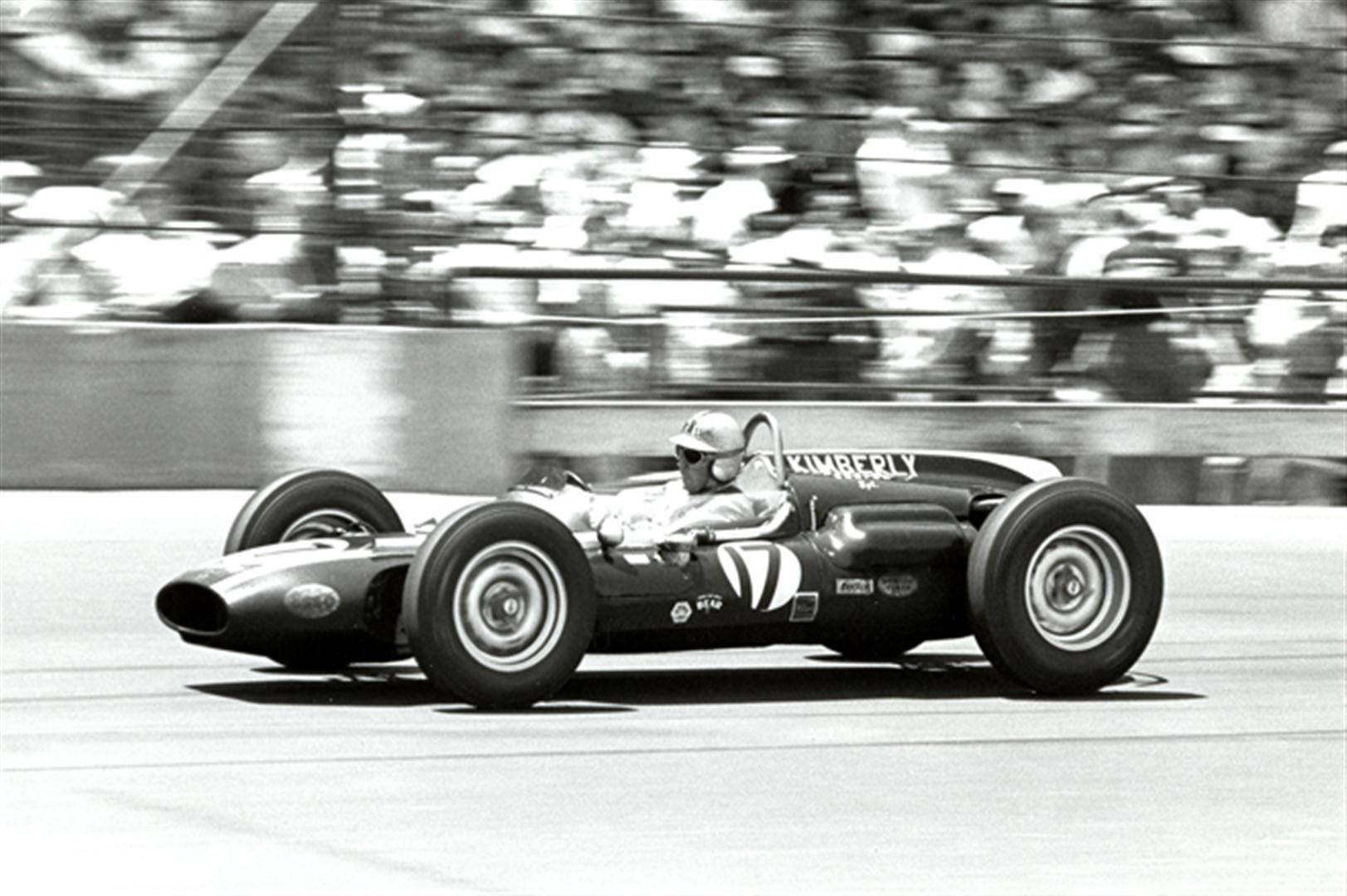

The 1960s saw two main design concepts become prevalent throughout the decade, but it was the low slung cigar style which dominated Formula One before the first instance of aerodynamics filtered through, thereafter, dramatically altering established design concepts. The finest example of the cigar style was the Lotus 25 introduced in 1963. The subtly curved shape of this car gave it the look of a missile whilst the iconic yellow stripe running down the middle of the British Racing Green paintwork only added to the irresistible appeal of this car for any racing fan. In short, it was the epitome of classically understated British design. It did not have polished chrome wire wheels or a flamboyant exhaust layout, nor was it finished in an overly bright and passionate colour yet this is where its appeal lay. By the mid-1960s, most of the teams on the grid were British, which meant that this design principle HAD become the accepted design concept in F1.

The only significant team on the F1 grid during the 1960s who emphatically did not follow the understated British approach to design, was of course the Ferrari team, led by the charismatic yet autocratic Enzo Ferrari, who first introduced the new approach to design by attaching wings to their cars in 1968. Their first attempt at this visually striking design proved to be another winner for the team with the surprisingly low profile nature of the rear wing in comparison to the rest of the grid, only adding to the appeal that this car had on your eyes. The final compliment to the beauty of this car is the iconic shade of Rosso Corsa red, which all Ferrari racing cars are decked in.

Moving into the 1970s, Formula One went through a period of rapid innovation and change which altered the nature of its design, moving it yet further from its starting point in the 1950s. During the decade the old cigar style was rapidly ditched by teams who instead embraced wider and bigger cars, complete with big front and rear wings. The subtle differences between the teams during this period are best exemplified by the 1972 Lotus 72 and the 1975 Ferrari 312T.

Firstly the Lotus 72 shows the remarkable advance in F1 design as this car was introduced only two years after the Ferrari 312 pictured above. This approach was innovative because it was the first with the wedge shape design that became the norm throughout the 70s. This wedge shape centred on the radiators being mounted either side of the engine at the rear, a design concept which is still adhered to today. The increased size of wings in Formula One also helps to give the car a wider profile in comparison with previous eras, giving it an air of solidity.

Secondly the Ferrari 312T, which appears to be slightly shorter than previous cars of the 1950s and 1960s, is unmistakable amongst the wider track nature of the cars of the 70s. Whereas most other cars on the grid appeared to be far wider and chunkier in design most of the Ferraris of this period appeared to take a more sculpted and narrow design principle which helped to further the idea that Ferrari were a completely different team to anyone else in the paddock, despite the fact charismatic owner Enzo Ferrari rarely attended any races during this decade.

By the 1980s, there was an explosion of technological advances in F1 with many new design concepts being trialled at this time. The two most evocative cars during this decade were the 1983 Brabham BT52 and the 1988 McLaren MP4/4. The Brabham was innovative as it was the only car of this period to go without the traditional wedge shape design, instead putting the radiators at the very rear of the car. This gave the car the unique impression of a dart-like missile at the front, but, in contrast, being very wide at the rear. However, despite this car being successful, it was not a design concept much copied by other teams, mostly because the upcoming turbo domination of F1 required much larger fuel tanks which rendered this very narrow design impractical for the 1984 F1 season. Moreover the fact that this design appeared very late that year meant that the other teams could not drastically alter their own design to copy the Brabham during the season, therefore leaving it as a one-off piece of F1 design and innovation.

Here you can see the sleek dart-like front end of the car plus its much wider rear end with the radiators elongating the design by the engine.

On the other hand, the 1988 McLaren MP4/4 was the most iconic of the sleek 1980s F1 design, with the car appearing to share its design philosophy with a skateboard with its elongated, narrow shape. This car is the very epitome of the now traditional ‘coke-bottle’ design of the front and rear end being tapered with only the radiators adding to the width. The bodywork was very svelte and sleek in profile, with the lack of any aerodynamic pieces that spoil the understated beauty of this car.

The 1990s saw the innovation of the previous decade carried over, with car technology rapidly evolving. Two significant cars of this period were firstly the 1990 Tyrrell 019 and the 1998 McLaren MP4/13. The Tyrrell is important to F1 design because although it was not a competitive car, it was the first to introduce the raised front wing concept. Their anhedral front wing proved to be a technical innovation copied by most other teams at the time and something that is still prevalent in F1 today.

The second significant car of this decade is the 1998 McLaren MP4/13. Whilst this was not a car that produced a lot of design innovation, it does however perfectly highlight the increasing influence of aerodynamics in F1 design. . The intricacy of details such as the suspension setup shows an increasing attention to detail, with every part of the car now being designed with performance in mind.

The 2000s have so far proved to be the zenith of aerodynamic influence in F1 design with the two most extreme examples being the 2008 McLaren MP4/23 and the 2012 Ferrari F2012 . The McLaren was the last of the cars designed to a far more open rulebook, owing to a change in regulations introduced in 2009, which banned extraneous items such as barge boards and winglets, as seen in the photo below. This car has ultimately proved that, by now, every aspect of its design was solely focused on performance, leaving little or no room for conventional beauty in this highly competitive sport.

The final example of F1 design in this overview is the 2012 Ferrari F2012, which must surely be labelled as one of the worst F1 designs of recent times in terms of aesthetics. After taking advantage of a further rule change introduced in 2012 – implemented to improve safety – most of the teams designed their cars with a step in the nose. This proved to be unpopular with fans, though, who did not like its ungainliness, yet it remained a feature that has now entered the F1 design lexicon. Ferrari, however, have taken this to the next level with a design more akin to something produced on an etch-a-sketch than by an internationally renowned design studio. The very high nose only serves to reinforce the lack of grace displayed by the front end of this car.

Whilst aerodynamics are monopolising F1 design, they are simply a direct reflection of the increasing competitiveness of the F1 teams as they use every nuance to increase their cornering speeds and consequently their lap time. Formula One has now transcended elements of both sport and business with the commercial interests of the teams linked to their performance on track. The prize money awarded is directly linked to their performance over the season so it pays both in the race and in terms of sponsorship, to be successful on the track.