STEFAN MILENKOVICH The Man Who Speaks the Language of the Eighth Note…

February 23, 2015

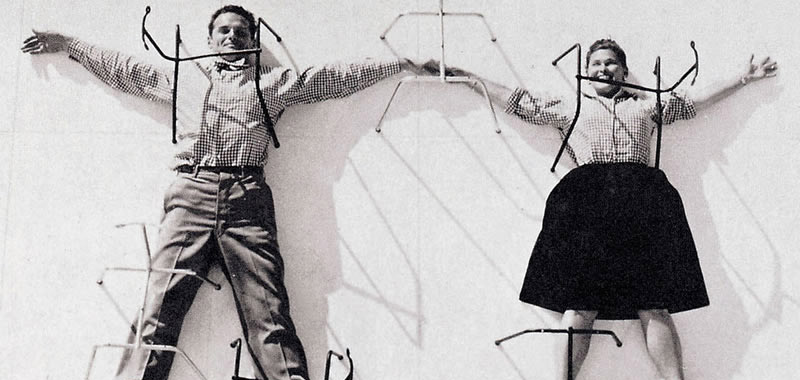

Closing the Gap: Women and Furniture Design

March 4, 2015Music is a constantly evolving, ever-changing language. Joana Carneiro, acclaimed young Portuguese conductor speaks it fluently. A rising star in the rarefied world of orchestral conducting, she communicates to listeners with both aplomb and passion. Writing for this special, women-themed issue of Dante’s about my conversation with Joana Carneiro in what may be one of the least gender-specific European languages – English – is an interesting, if somewhat contradictory, premise. Carneiro herself embodies some of these contradictions as a woman who is a powerful presence in a male-dominated field.

She is, at 37, one of the world’s most formidable young conductors or Maestrinas. Recipient of numerous awards such as the 2002 Maazel-Vilar Conductor’s competition at Carnegie Hall, Carneiro has, since 2009, been Music Director of the Berkeley Symphony Orchestra and for the last year has also been working with the Gulbenkian Foundation Orchestra. Between these two permanent collaborations, Carneiro has been engaged by some of the most prestigious orchestras, philharmonics and concert halls. This has, over the past four years, also included increased experience as an opera conductor, from the Peter Sellar’s stagings of Stravinsky’s Oedipus Rex and Symphony of Psalms in Sydney, to the Cincinnati Opera’s production of The Flowering Tree by John Adams.

A native of Lisbon, Carneiro comes from a well-known family. Both her mother and father were and are in politics: one as MP, and the other as a long-serving Education Minister. Her parents are what would be described in the UK as upper middle class. Highly articulate, devoted to their children – all nine of them musicians and/or singers – it could be said that there is a certain ordinariness in the way that these extraordinary families all are. Arriving at Carneiro’s home during a sleepy, Lisbon August, in a recently developed part of the city, I find myself in what used to be a large well-appointed nineteenth century Manor house, gazing out, not at crops, but at tall apartment buildings rising from what were once the house’s holdings. Looking at the sophisticated, jeans-clad Carneiro, one senses the solidity of her upbringing, which – together with the passion that drove her to become a member of one of the most exclusive clubs in the world, that of the Maestrinas – makes her exude a quiet brand of confidence, one that is not afraid to smile.

As a mere lover of music myself, before meeting with Carneiro and talking with her I was reminded of something Proust said: ‘The voyage of discovery is not in seeking new landscapes but in having new eyes’. In this case it was about trying to understand some of the most superficial intricacies of a language one does not speak, but nevertheless likes the sound of.

Women Composers – why only so late?

Over a hearty Portuguese espresso, or ‘bica’ as it is called in Lisbon, I start by expressing my surprise to Carneiro at the difficulty I had, when looking at the history of music, in finding female composers. Musicians, interpreters, performers there were many. Composers there were too few leading up to the twentieth century. I couldn’t find many more noteworthy names than Fanny Mendelssohn, Felix Mendelssohn’s sister, or Clara Wieck, later married to Robert Schumann.

Carneiro replied by rattling off a long list of names of women composers of the second half of the twentieth century, a time when, according to her, greater gender equality helps explain their appearance. Even so women are still a minority in music composition.

She went on to add that in conducting, the premise – the organising metaphor – has been that the Maestro is the leader, the guiding hand. Historically, there were no cases of women conductors, at root because of the denial of female authority. As a result the feminist turn-around – the reversal of the established order – has been, in a way, even harder. So she has been particularly thankful to women such as Baltimore Orchestra and São Paulo State Symphony Orchestra conductor Marin Alsop; or to Australian-born, Hamburg Philharmonic conductor Simone Young; or to Susanna Mälkki, a Finn heading the Pierre Boulez-founded elite French music school, Ensemble Intercontemporain; or also to the Chinese-born New York Orchestra Conductor Xian Zhang.

Joana Carneiro points out the introduction of the ‘blind audition’ system last century as another stepping-stone. After this system, by which examiners could not see who was applying to play, was introduced the gender composition of orchestras drastically changed with greater equality achieved.

Globalisation and her not-discontents

At a time when globalisation is criticised by so many of those it has left behind, it is being hailed as a force for good by most of the music world. Carneiro starts by commenting how much technology and the somewhat less restricted movement of peoples and ideas have led to a democratised, increasingly shared music creation and music enjoyment experience. She points out that several orchestras and opera houses transmit a live Internet feed around the world. Anyone with net access can listen in. It is way too soon to say where this path will lead us. Carneiro is not convinced that national or regional or even continental music identities will fade. On the contrary she says that there may be two cumulative, concomitant trends. One trend is of fusion and merger, where we are witnessing collaboration between different countries’ musicians but also between differentiated music styles. The other is of a rally behind each country or region’s music traditions as people may fear the loss of national identities. Carneiro believes that most musicians maintain, in what they create or perform, elements pertaining to the places from which they come.

Carneiro, it could be said, is an advocate of former Singaporean diplomat (and current Singapore National University professor and dean) Kishore Mahbudani’s theory of The Great Convergence. His theory of The Great Convergence is that of one world, working together, closing in and maintaining the richness of differences at the same time.

I thought, at this stage, of a slight provocation to put forward. How would Carneiro explain that in Europe we saw three main countries at the forefront of music composition: Germany, Italy and Russia? Why had wealthy countries like the UK not had world class composers until later? Carneiro, on the contrary, looks at music, her history, her past and present in a more expansive and inclusive way than I have and therefore asserts that she would not identify these three countries as the main producers of the most prolific and relevant composers. She would include a Débussy and Ravel in France, an Elgar or Purcell in Britain, as well as composers from several Central and Eastern European countries in this group. When confronted with another possible effect of globalisation – that is a ‘mercantilisation’ similar to what one can observe happening in painting, with phenomenally successful artists doubling as CEOs of multi-million euro companies devoted to producing and reproducing lines of works that can be flogged off to investors who are no longer, in the traditional sense of the word, collectors – Carneiro argued that, even though music was a highly organised business, with the advantages stemming from that fact, she could not identify that as a trend due to the nature of music. This is especially because concerts are free-standing events, valued as a single occurrence and a moment, or an instant – even when the conductor, or players have performed that piece many, many times.

Music: atonal tonality

Music is not impervious to the time. I asked Carneiro how she saw a possible replication in music of the trend that is observable in painting – that is, the return to the figurative which is comparable to the controversy led in France by pianist and composer Jérôme Ducros at the Collège de France. Ducros is a far greater critic of the Vienna school than Carneiro who claims she derives pleasure, although differently, from tonal and atonal music. Carneiro says that wherever music goes in the next few years, be it to evolve back to tonality, or to a new form of it, it is still – like most other forms of art – a reflection of whoever we are at each era. According to Carneiro, music, composers, artists are always moving further ahead, ‘para a frente’. This happens despite the fact that there are moments of rupture and despite the fact that whatever happens further ahead is always, at least partially, connected to the past.

She believes that, as Oliver Sacks explains in his Musicophilia, it is music per se, whatever the school, that affects and has effects on us. It provokes dance, it changes the brain, it contributes to further development of a child’s brain. It has these effects, be it tonal and maybe more easily listenable; or be it atonal and not so automatically intelligible. The Portuguese caring-and-eclectic-music-listener Joana What does a conductor, who was educated in the classical, and let it be said, tonal music tradition, listen to? Only classical music? Far from it, says Carneiro, as she rises from her sofa and walks over to her hi fi to flick through some CDs she had recently acquired. She lists Portuguese styles such as Fado, artists like Carminho, or Gisela João, national ‘pop’ singers such as José Cid. She also indicates she has recently listened to Fatboy Slim, the Icelandic Sigur Ros, Copeland, Rolling Stones (she found their London concert, which she attended with her husband, an unforgettable experience) and a lot of Led Zeppelin.

And what about the way she listens to these different music styles? Carneiro says that she can’t really listen to music while talking to someone. Maybe that would be like trying to listen to two different interlocutors speaking two languages at the same time. She also adds that whenever she listens to a piece she has conducted or is rehearsing to conduct or to programme, she cannot help but listen to it in an analytical way, so it is not exactly conducive to a relaxing experience.

Aaron Copland is supposed to have said about the meaning in music that there is certainly a lot of it, maybe as much and as complex a meaning as in language – and the difficulties are equal to those one has in expressing meaning through words. It was therefore interesting to detect in the couple of hours I had the privilege to spend with Carneiro how often she repeated the word ‘afecto’. ‘Affection’, ‘fondness’ or ‘an attachment to’ may just about be the most singular way by which she remains, at heart, connected to her idea of Portugal. In this stance she is in the best of companies, like that of the seventeenth century Jesuit philosopher and master of the pulpit Father António Vieira: ‘To be born, Portugal: to die, the world”