Kem Issara: Fashion and Business in the 21st Century

March 7, 2015

ASIA HOUSE FILM FESTIVAL 2015

March 24, 2015China as a country, despite its monolithic tendencies as a political power, still produces creative artists that take the world by storm, inviting us into a specific centuries-old Chinese sensibility combined with the iconoclastic trends in the West. Laura Carniello for Dantemag meets just such an artist in Qin Chong.

Last year the 55th Venice Biennale opened up its exhibition spaces to a large number of established and emerging Chinese artists, one of whom was the well-known Qin Chong, an eclectic artist based in Beijing. Four of his paper sculptures were shown at Palazzo Bembo, where, together with other international artists, Qin Chong contributed to the success of the exhibition entitled “Personal Structures”. His artistic goals perfectly suited the mood of this event, since the stylistic and technical choices inherent in his works are far removed from the mainstream trends of Chinese contemporary art and trace an individual and unconventional path towards the reinvention of tradition. It was during this event I had the honour to spend two whole days accompanying Qin Chong around as his personal interpreter. We wandered through the Biennale pavilions, debating the hidden meaning of the works on show, while speaking about Chinese poetry and philosophy over a sandwich or enjoying some authentic Italian cuisine at the restaurant. All the way through he engaged with me with his pervasive spontaneity, the same spontaneity which shines through his works. The artist himself referred to it when I asked him in what way Chinese traditional culture influences his art, “Just as blood courses through the veins of every human being, the essence of my culture has an innate influence over me.”

Talking about the very beginnings of his love for art, Qin Chong takes me through his earliest memories: “Born in the countryside of Xinjiang province in the late 60s, I realised after graduating from middle school that you need a good education to build your professional future. Even though I couldn’t attend school under the best circumstances, art had a strong impact on me from the first year at primary school, starting with the very first art lesson in my life. I remember when those colouring textbooks were handed out to all my classmates, I was the only one who didn’t get one, since my parents were snubbed during Cultural Revolution for being landlords and, thus, class enemies in the eyes of the communist party. That lesson has stayed with me as one of my most vivid memories because that was the moment I gained my artistic enlightenment. As for contemporary art, since it had a late start in China, I only came into contact with it in 1986, when I chose it as my main subject at art college. Then in 1987, when I was studying in Beijing, I set up my first workshop, transforming a room of just ten square metres and it became the starting point for my artistic activities. It was there I spent all my free time and school vacations of three out of my four college years, producing art. It was only in 1994 I was finally able to pay off the landlord for all the rent I owed him!”

In 1993 Qin Chong founded a private gallery for Chinese contemporary art, The Ammonal Gallery, in the Beijing artistic quarter in the former summer palace Yuan Ming Yuan. He continues with his life-story, “In 1999 I moved to Berlin, where, until 2001 I was based in the artists’ building Tacheles, then from 2001 to 2005 I worked at the Künstlerhaus Mengerzeile.” Qin Chong feels this significant experience in Germany was the spark that ignited his true artistic identity, inseparable from the traditional Chinese culture which naturally runs through him. Moreover he admits: “As to contemporary art in the strictest sense of the word, it was only in Germany that I began creating my work.”

After 2005 he decided to return to China, charged up with positive energy, motivated by a series of successful exhibitions and, above all, possessing a new, strong awareness of his creative possibilities and sources of inspiration. That was the greatest proof of the artist’s visceral bond with his homeland. 2007 was the year when Qin Chong was finally able to settle, establishing his private studio in Songzhuang, the artists’ village, east of Beijing, where he is currently based.

During his artistic career, he has curated and contributed to many exhibitions in China and abroad, of which some of the most significant ones have been “Chinese Art in Berlin” (Berlin 1997), “Young Art from China” (Hamburg 1998), the solo show “Shadows” (Switzerland 2002), the first Beijing Dashanzhi International Festival (2004), the trilogy of solo exhibitions “Grey” (Shanghai), “Black” (Berlin) and “White” (Hong Kong) in 2005, the 4th Biennale in Prague (2009), the solo show “Whatever” (Guangzhou and Hong Kong 2010), contributing to the International Biennale of Paper Art (Sofia, 2011), the solo show “Endless Polarity” (2012) and an exhibition at the Art Stage (Singapore 2013). Despite the importance of all the these professional achievements, Qin Chong seems to be particularly affected when I ask him which exhibition was the most stand-out for him, “Well, the one which had the deepest impact on me was the one before graduating from art college in 1990 in Beijing. It was March 1987 when I was huddled on my bed in my empty ten square metre room, wrapped in a blanket, while, outside, in the small garden, a freezing wind was blowing in a low moan.and I started dreaming about something I had so long been looking forward to and preparing for – my final year solo show, my so-called “flow of inspiring thoughts”. That period determined the artistic path I am still treading to this day. Even at that early stage of my career I knew that I would find my way as a freelance artist.”

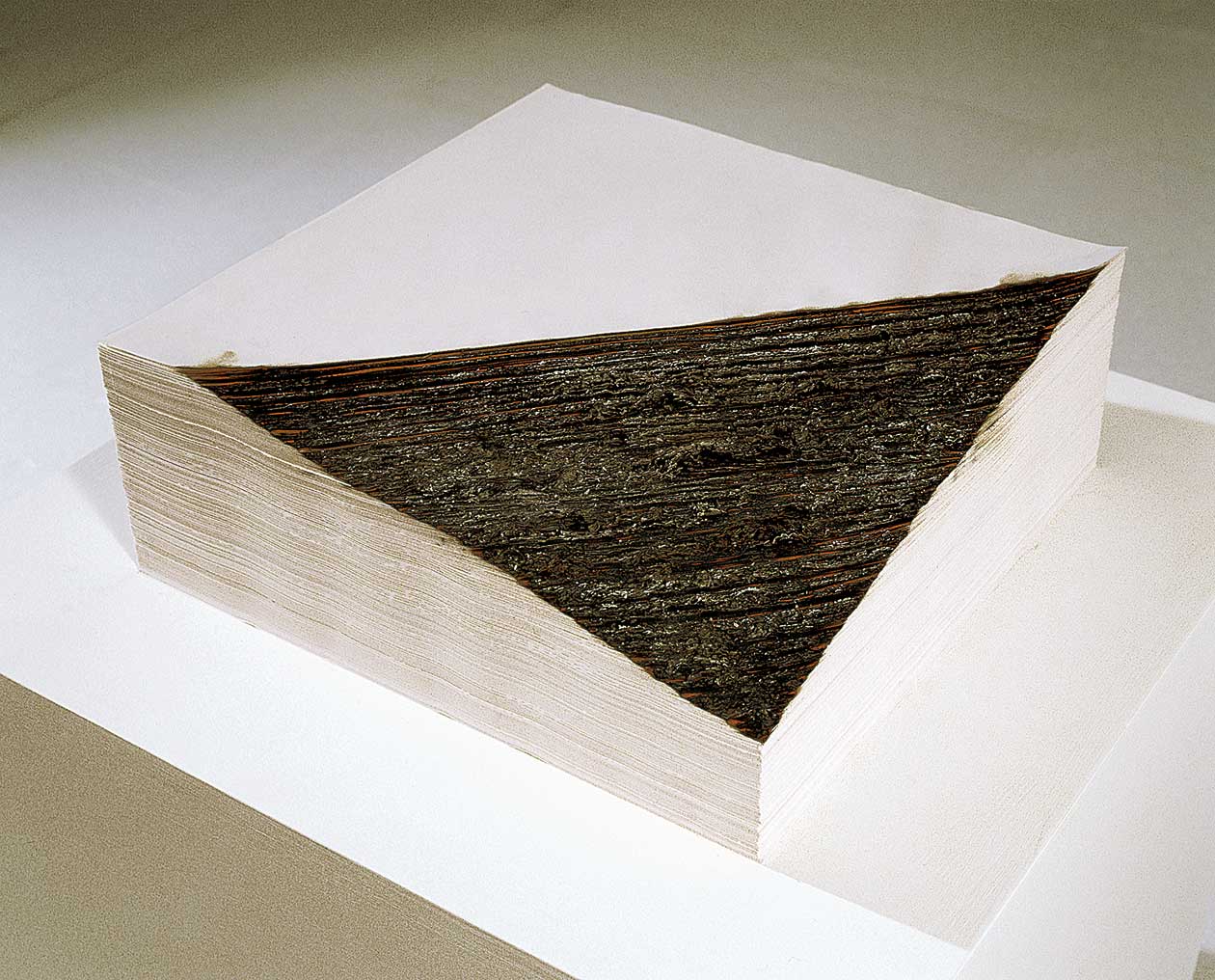

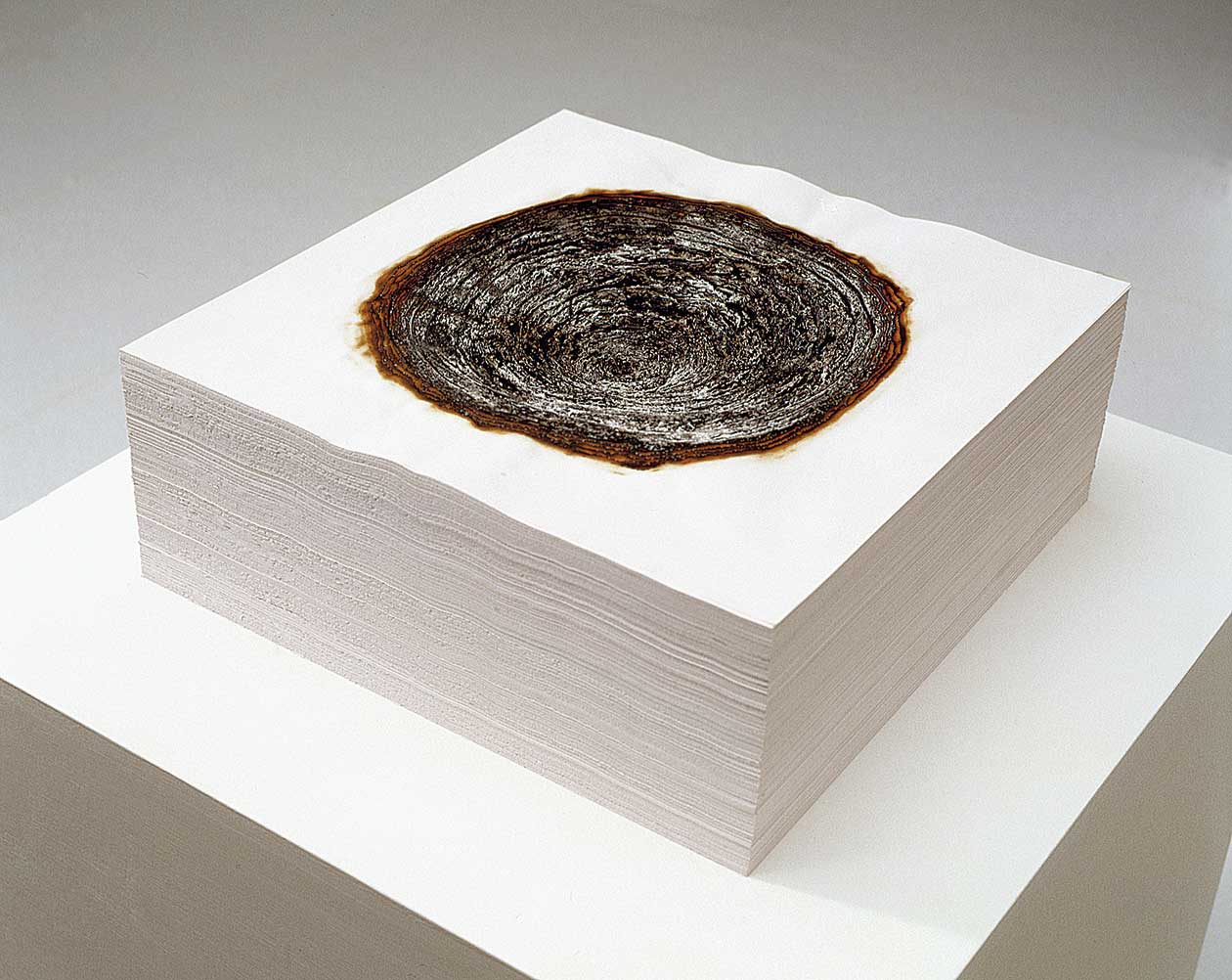

Even though Qin Chong had been in very close contact with the trends of European contemporary art – and he divides his time between Beijing and Berlin – the essential nature of his art clearly has Chinese culture at its heart. More specifically, the artist lists four main precepts that best describe the core features of his artistic process: “Black and white as a matter of principle; being in tune with the spirit of his culture; to convey a meaningful style and finally to use materials of all kinds”. The first two elements reflect how much the artist respects his country’s traditions, although this innate connection doesn’t force him to be stuck in the past, nor impose creative boundaries on him. Thus he says: “Every time I create something I first consider the message I want to convey and, then, I select the materials and the techniques which best realise what I want to communicate. […] All of my works are different as to which materials I use and how I organise them, but, at the same time, each one of them reveals my very own language, that meaningful style. I am a very thinking person, but I get my inspiration from everyday life”. Qin Chong’s art abounds with contradictions and dichotomies – black and white, paper and fire, past and future, old and new, concreteness and illusion, lightness and heaviness. A perfect example is one of Qin Chong’s signature works, the installation “Past-Future”, first shown in 2002 in Berlin. Subsequently it figured in many exhibitions, in Beijing, Shanghai, Tokyo, Sofia and, most recently, at the Galerie du Monde in Hong Kong. The installation consists of several vertical paper cones of varying heights, with burnt rims – the uncertain, long or short term future. The ashes scattered all around the irregular cones – symbol of the silent, dead past – are gradually removed by the visitors feet as they are invited to walk over them as they view the piece. Working with opposites the artist is constantly seeking a balance between them. He says: “Only if you discuss and reflect the two poles, birth and death, can you improve what lies in between, what your existence amounts to, your present life.” Besides exploring the concept of time, explicit in the work’s title, Qin Chong’s intention is to convey a sense of struggle between materials and, thus, meanings, by playing with a technical device typical of his style; he uses a powerful element like fire to deal with the delicacy and the fragility of paper. The paper sculptures shown at the 55th Venice Biennale are very closely related to this conceptual approach.

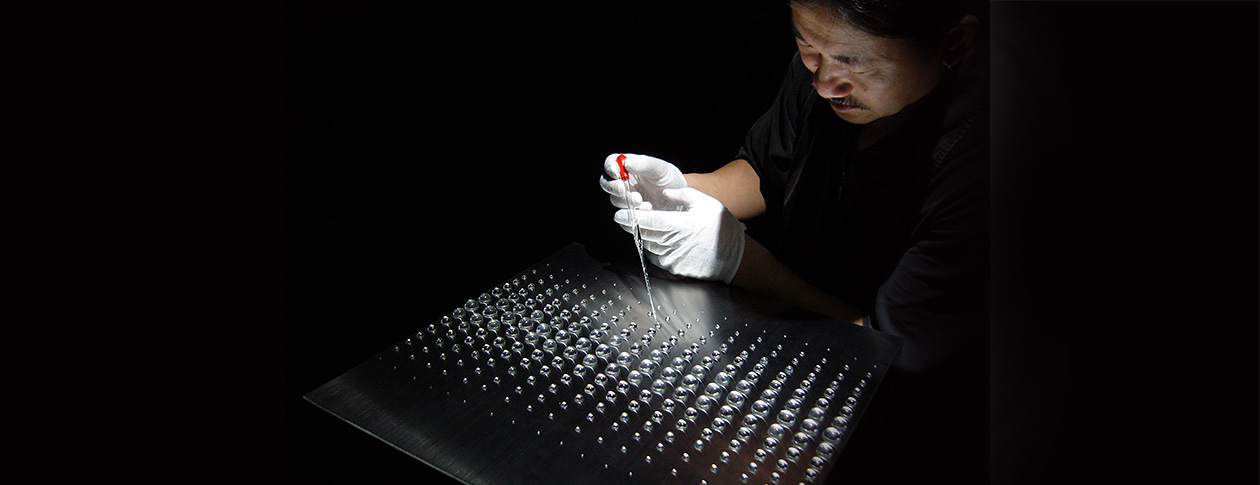

Another work which encapsulates Qin Chong’s artistic language very well is “Up to the Limit” (2000), an installation composed of nine metal stands onto which he has created patterns made from drops of water, which gradually evaporate over the course of the exhibition. Again, we are dealing with an example of a double contrast: the polished and fixed metal stands come into contact with the irregular and disappearing water drops. Moreover, the work combines and harmonises objects that are forged, literally, by human beings with that freely available natural element, par excellence – water.

Qin Chong’s creations are conceived and born out of that traditional dualism between Yin and Yang, the contrasting and complementary principles which permeate the Chinese perception of reality, in other words, “The ten thousand beings carry the Yin on their back and embrace the Yang” (Laozi 42). That is exactly the shared philosophy which is the basis for all of Qin Chong’s work, a cultural heritage which he “genetically” owns as a Chinese native. However, he does not work in restrictive structures; the way he handles the raw materials he finds in the five natural elements (water, fire, metal, earth and wood) shows his insatiable curiosity to explore new techniques and art forms, thereby revealing his innovative take on experimentation.

As for his devotion to black and white, Qin Chong once wrote: “These days mankind is developing so rapidly – news spreads as quick as lightning, cultures are interweaving, societies are as transitory as wind and clouds, people are weighed down by all kinds of pressures. The world is so full of colours! I want to find my own equilibrium in the king and the queen of colours, black and white.” In the late nineties, the artist decided to give up using bright colours and embraced the meaningful aesthetic of black and white, using them in a variety of innovative ways and techniques. His work “Losing” (2001), which comprises twenty-four paper rolls blackened by soot, expresses mankind’s concern for its influence and its ability to transform nature and it is a very good example of his art as rooted in philosophy.

Qin Chong’s creative genius transcends the category of ‘contemporary art’, while perfectly responding to its value criteria, and goes beyond mere tradition. Consequently, despite their apparent simplicity, his paintings and installations have a strong evocative and alluring power, both for a Chinese and a Western audience. “I think there is no need to try to explain an artwork that does not tell its own story”, he says. And indeed, when viewing his works, we should abandon any attempt to define them by any rigid classifications. What we should do is just follow the example of their creator and contemplate them with spontaneity, and allow them to appeal to our emotions rather than to our mind.

For me personally, as a scholar of ancient Chinese art, I feel very close to the spirit of Qin Chong’s work. He is the living proof that tradition never dies, a black swan among the increasing number of contemporary artists who want to destroy it by any means in their pursuit of the myth of “here and now”. Nevertheless what intrigues me the most about Qin Chong’s art is the way it reflects mankind’s present condition by, on the one hand, drawing on age-old elements of Chinese culture, while, on the other hand, constantly searching for experimentation and spontaneity.