How seriously should we take ourselves? Erwin Wurm interviewed by Reya von Galen

April 24, 2015

Letter from the Editor

May 7, 2015Brussels: The New Arts Capital of Europe?

A neon by Filip Gilissen in the basement of Komplot © Vincent Matthu

Berlin, once the mecca for European artists and gallerists, seems to be losing its aura. Artists, gallerists and collectors seem to be flocking instead to Brussels. Dantemag was in Brussels during Art Brussels, the contemporary art fair and asked Frédéric de Goldschmidt, a French art collector who lives in Belgium, to tell us why.

Belgium has a very long-standing tradition of art production and collecting that goes back at least as far as the Renaissance (Brueghel lived in Antwerp and Brussels). In contemporary terms, though, the economic boom in Flanders in the second half of the 20th century meant that collectors like Herman Daled (who recently sold his entire collection to MoMA) had the financial means to realise their passion and build up original and personal collections. At the same time that they were a source of pleasure for the collectors, the collections also demonstrated their success to people inside Belgium and beyond. These early collectors created the image – one could even say the legend – of the Belgian collector.

These collectors stood out because they were committed to artists who had not yet had any of the visibility and the recognition they enjoy today. The collectors came from Courtrai, Ghent – they were visionaries and they built up collections of museum-like proportions, especially in Minimalist and Conceptual Art. Mostly Flemish, they were later joined by French-speaking (and even French) collectors, like Eric Decelle who maintained this curious, open, and forward-looking vision.

The liveliness of the market has been stimulated by the great annual event that is Art Brussels, one of the oldest and most convivial art fairs in Europe. According to Katerina Gregos, its new artistic director (and originally from Athens), “Brussels is the art-capital-in-progress of Europe.”

Her colleague, the artistic director Laurent Boudier of Slick (an off fair that chose to set up an edition in Brussels last year), points out that “it is an incredible spot between Cologne, Amsterdam, London and Paris.” Johan Tamer-Morael, the founder of Slick, says that “Belgian collectors don’t look at established values; they buy with their heart.”

Not only are there fewer collectors living in Berlin, but Belgian collectors give on-going and friendly support to artists. Belgians do not like doing things in an over-complicated way. They prefer to buy art directly rather than to support it through institutions. Buying art is a way of spending one’s money to affirm one’s personality, discreetly or blatantly, but always because it is a pleasure.

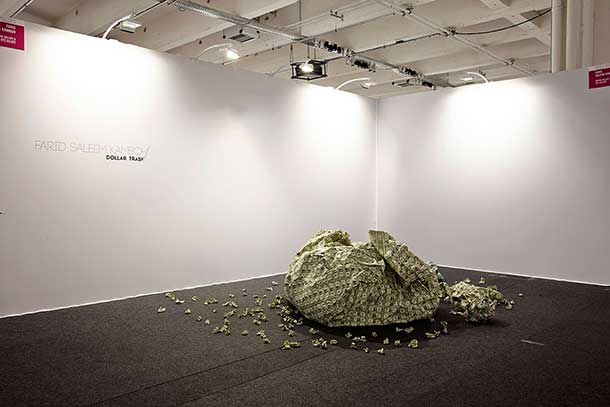

Dollar Trash by Kuwaiti artist Farid Saleem Kamboh at Slick

The early collectors invited foreign artists like Peter Downsborough to work in Belgium and the artists ended up liking it. Others artists, drawn as much by the quality of life, the availability of space and the moderate rents as by the access it provides to these legendary collectors, followed from everywhere. Among these artists are the South African Kendell Geers, the Cameroonian Pascale Marthine Thayou, the Swiss Marie-José Burki and Beat Streuli or the Frenchman Lionel Estève.

After the early pioneering gallery owners like Marie-Puck Broodthaers, Isy Brachot, Greta Meert or Albert Baronian, others such as Xavier Hufkens or younger gallerists, such as Olivier Meessen and Jan De Clercq manage to combine the artistic requirements of collectors with a good relationship with the artists –and vice versa. Collectors and artists attend the same dinners. Events are very open and everyone is good-humoured. Rodolphe Janssen regularly sets up a stall outside his gallery serving French fries!

Several foreign galleries like Barbara Gladstone or Almine Rech have made Brussels their first or second home. These galleries are happy to exhibit artists who are established in Brussels. This is good for the gallery because artists already have a following of friends or admirers, who will come to private viewings and buy at the gallery. It is equally good news for artists, as the more galleries there are in the city, the better chances they have to be represented and exhibited.

The galleries open up rich possibilities, make Brussels more dynamic with their varied programming and, in turn, create a new generation of Belgian or foreign collectors. Some collectors have fewer funds and less specific requirements (perhaps they might frequent The Affordable Art Fair – which is what it says), others have fewer funds but quite specific requirements (they might start with limited editions) and there will of course also be some who have plenty of means, no specific interests and will be happy to follow market trends and latch on to the latest artist à la mode.

Entrance to Komplot. Photo: Vincent Matthu

All this happened without a public plan. Belgian artists have recourse to fewer resources than is the case in France or Germany. There are only limited regional or national funds, and no tax scheme that attracts artists as Ireland tried to do.

Belgium tax laws are generous, though, for those who have money, and combined with the opportunity of finding high-quality real estate at a reasonable price, the favourable tax environment could attract foreign collectors. According to Laurent Boudier, “collectors who had storage space in London or Basel are now coming here.”

It is also worth mentioning that it is in Brussels where one can find one of the few restorers dealing with contemporary art only. Nicolas Lemmens has a 2,000 sq. ft. studio and employs three people. “My main competitor is in New York.”, he says.

Opening day at Art Brussels

Something quite peculiar to Belgians in general and to Belgian art-lovers in particular is that they travel a great deal and, especially, attend an enormous number of international art fairs. In Basel or Miami where the main world fairs take place, you can find practically as many Belgian VIPs as French.

Although there is no museum of contemporary art in Brussels, the opening of Wiels has also played its part in enhancing this dynamic identity of Brussels, elevating its position in the world by organising exhibitions of an international scale with foreign big names like Mike Kelley and Rosemarie Trockel, but also Belgians like Francis Alÿs, Luc Tuymans or Joelle Tuerlinckx. Following the Wiels or Brass who took over a former brewery, curators can also take over unexpected locations like, as was done recently, the floor of a hospital.

‘Document’ by Guillaume Bléret and Patrick Carpentier

for Poppositions off fair

The fabric of artistic life in Brussels is enriched and given a real party feel by associated and alternative threads – young artists and curators who show at Etablissement d’en face or Komplot then hit the bars like Daringman or Midpoint, both of them in Rue de Flandre, close to the downown area of Brussels where many galleries are located.

It is this social life artists are enjoying, as much as the relative easiness of finding good-sized studios at good prices, that is the reason Brussels is now being talked about as the “new Berlin”. Belgian collectors attracted gallerists who attracted artists who attracted art workers, gallerists and collectors, in a real virtuous circle!

Hufkens Horn Gallery

Canadian artist Zin Taylor explains the attraction for him: “I don’t like Berlin and Paris is too expensive. Although I don’t speak French, I feel at home in Brussels. Brussels is a kind of ‘no zone’. As a Canadian familiar with the loser syndrome we have towards the US, I appreciate the humorous self-deprecation that Belgians are capable of, their relationship to the weirdness, the ‘hiddenness’. Brussels is full of hidden secrets. At the same time it’s cosmopolitan and a good community.”

Guillaume Bléret and Patrick Carpentier have been successful in attracting foreign talent for events such as Document, which was part of Poppositions an alternative art fair, combining artists and DJs, because “thanks to its cultural mix (Flemish, French and others), Brussels is quite developed for a small city. There are lots of different scenes and clubs, such as Fuse, that have been active for many years.”

A performance by Oliver Beer at Wiels © Cici Olsson, Experienz performance

& live art platform, Brussels

Belgian graphic designer Audrey Schrayer, of Codefrisko, who works for many clients in the arts world, points out that Brusselers are “zinneke”. Zinneke is a word used in an old Brussels dialect for mongrel dogs, taken from the name of the now-covered Senne river that used to run through Brussels.

Aleksandra Eriksson, the young Polish-Swedish coordinator of Poppositions, which took place this year for the second time, came from Sweden for Brussels. “In Brussels,” she says, “there isn’t one way to act; there is no standard behaviour. I came here to do what I wanted to do, without having to define myself.”