“Not Your Mother’s Hysterectomy: A Transformation in Women’s Health Care”

April 18, 2015

Manfred Zylla

April 22, 2015Cima da Conegliano: The Poet of Landscape

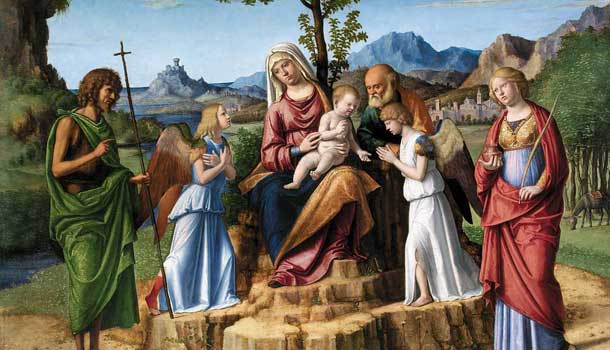

The Flight to Egypt with St. John the Baptist and Lucia, Lisbon, Calouste Gulbenkian Museum Photo: Catarina Gomes Ferreira

Like postcards from the past, an extraordinary exhibition in Paris of the works of Giovanni Battista Cima da Conegliano reveals the landscapes of 15th and 16th century Italy to modern eyes..

“If you leave Venice and travel for about two hours on the train – maybe the fast Saturday evening service, full of students and workers – you get to the borders of the Veneto region and then, like a cinema fade, you come into the Friuli region. The landscape doesn’t seem to have changed that much, but if you are astute you can sniff something different on the air. On the Livenza, you no longer see the countryside you recognise from the paintings of Palma the Elder and of Cima. The mountains have given way, in the north, to streaks of gravel scree and the black of woods, barely perceptible against the great veil of cloud. Just inside Friuli, there are initially only plateaus and sky; then you notice the water ditches getting more frequent and the rows of mulberry trees becoming thicker, elder tree copses, sorghum fields on the bordering land. The houses are no longer so rose-coloured, their front yards swept clean, as if for some party, their barns with the rigid and compact hay bulging through the supports. But it’s especially the smells, streaming into the now emptied train compartment, that are so different; the smell of a land of romances, of a region on the margins.”

Madonna and Child,

Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale

Thus Pasolini describes with extraordinary sensitivity that place where the Veneto mutates into Friuli. It is no coincidence that he mentions the paintings of Di Palma and Cima, two of the artists who were so much concerned with nature, with light, and with landscape. This well-known passage, taken from A Land of Storms and Primroses, belies the same intimate acquaintance with the places and the landscape that we see in the meticulous and sensitive eye and paintbrush of the master painter from Conegliano. Cima was given the title “Poet of the Lndscape” on the occasion of the exhibition his home town dedicated to him in Palazzo Sarcinelli in 2010.

This venture exhibited over forty works and was produced and organised by Artematica, curated by Giovanni Carlo Frederico Valli, who was aided and abetted by a committee of experts that included the foremost academics from Italy and abroad: Peter Humfrey, David Alan Brown, Mauro Lucco and Mario Ceriana. The works were loaned from public art institutions such as the National Gallery of London, the National Gallery in Washington, DC, St. Petersburg’s Hermitage, and Le Gallerie dell’Accademia of Venice. The exhibition’s aim was to reconstruct the artistic life and works of Cima, one of the major interpreters of figurative art, who bridged the 15th and 16th centuries. It also sought to demonstrate that he was an equal protagonist, not just a follower, whose genius was of the calibre of Giovanni Bellini and Giorgione di Castelfranco.

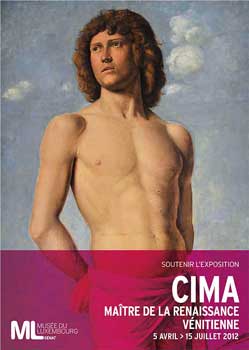

Don’t worry if you let this magnificent exhibition slip you by. You’ll be able to savour it in Paris at Le Musee du Luxembourg, from April 5th to July 15th under the title, Cima, Maitre de la Renaissance Venetienne.

Le Musee du Luxembourg, from April 5th to July

15th under the title, Cima, Maitre de la Renaissance Venetienne.

But who was this Cima da Conegliano and, in particular, what is his place within a period of art, more often than not associated with the Veneto school at the end of the 15th century? The facts of his life are rather sketchy, due to the dearth of surviving documents. There are some significant blanks, such as his exact date of birth. It is assumed to be between 1459 and 1460, based on an entry in the Conegliano tax records of 1473, where we can make out a certain Joannes Cimator, very probably 14 years old since it was from that age, according to Veneto law of the time, that a person had to start paying his own taxes. The artist, who left us with a plethora of signatures but not a similar number of dates, does not consequently give much help to art historians. This vague chronology also poses a problem as to his training. Tradition has it (notably Vasari) that he was trained by Bellini, whereas modern critics place him in a much more strictly local tradition.

We have some evidence of his stay in Vicenza to paint an altar-piece for St Bartolomeo church – a confident signature and date “Joannes Baptista de Conegliano fecit 1489 a di primo marzo (“Painted by Giovanni Battista de Conegliano in 1489 on the first day of March) – where we also have evidence of his contact with Montagna. This was also the year he moved permanently to Venice in order to open his workshop there and begin his successful career.

Cima’s refined classical style was distilled out of a melting pot, frequently on the face of it insoluble, of mutual influences. He used what he learned from Bellini, with their shared feeling for nature. He absorbed from Lombardo that volumetric purity of his figures. The kind of “theme and variations” seen in the crystal clarity of his altarpiece works were a distillation of Antonello da Messina’s style, taking in on the way Alvise Vivarini.

Madonna and Child,

Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts

de la Ville de Paris

© Petit Palais / Roger-Viollet

This is indeed compensation enough for the paucity of documentary evidence, leaving us as it does to the joy of appreciating these works, which are of such high quality and whose power has not diminished over the course of the years.

Whatever his training might have been – which encompassed, as we have mentioned, a variety of influences – we come up against a painter who paid enormous attention to nature and landscape, so much so that some locations he painted are still identifiable in the geography of today.

The Doubting Saint Thomas

Venezia, Gallerie dell’Accademia

On a par with his numerous depictions of saints and madonnas, where he adopted the forms of the period into a polarity which veers from touching pathos to enquiring psychology, we are also left with landscapes that represent the real magic of his painting. As Giovanni C.F. Villa explains in the catalogue for the 2010 exhibition, “His art represents a real communion with his natural environment, which is so intense and inseparable that it arouses a quasi-metaphorical sensual experience in us, akin to breathing in fresh air, the fragrance of flowers, the aromas of greenery, the smell of the earth – a taste of truth. His cultural world is immense, refined, cosmopolitan, all existing in one unique city – Venice across the 15th and 16th centuries – that was indeed the art capital of Europe. And that’s not all. The man from Conegliano, thanks to the richness of his patrons, the prestige of his workshop and the abundance of his commissions, was one of the leading lights in this city, where painting at the same time we find Bellini, the Vivarinis, Carpaccio and Giorgione.”

The Venice of this period saw the existence of workshops that were working to a very high, if not the highest, quality and which were responding to a knowledgeable religious and middle-class patronage that would bring artistic and financial success to the master painter from Conegliano. However, it also set his own taste for the reliable and frequently conventional forms of devotional art. The years between 1494 and 1515 saw him working mostly in the part of the city bordering the lagoon, in the San Luca quarter, where he was to marry twice and father eight children.

Giovanni C.F. Villa explains: “In the 1490’s, it is Cima, along with Giovanni Bellini, who became the great inventor of Italian skies and landscape. He painted them with a poetry capable of spanning centuries and therefore they are still relevant today, with their valleys and stone formations contrasted against the intense depictions of dawn and sunsets that forge man and nature into an indissoluble unity. He it was who paved the way for Giorgione, Titian and the substantial period of the Venetian 16th century.”

The decade of the 1490’s produced a plethora of magnificent examples of Cima’s work: The Madonna of the Oranges where “the delicate light filtering through the fresh green of the pristine leaves bedews the noble and solid saintly figures” (Bocazzi); The Madonna and Child of London, finished, according to Humfrey, shortly after the one in Genoa in 1496, which remains the most beloved and repeated formal type on his well-known devotional theme; Il San Sebastiano, on a more political theme, from the San Rocco church in Mestre where, drawing on Lombardi, the most exquisite nude figure soars up “like an ivory tower into the skies above”(Longhi); the San Girolamo of London, which is also a prototype for a series of variations on the theme of the relationship between the figure and its landscape; The Blessed Conversation of Parma, where, by his clever use of light blending the figures into the shadows, a mood of melancholy emerges, alongside a structural harmony that recalls Bellini.

St. Elena,

Washington, National Gallery of

Art, Samuel H. Kress Collection,

1961.9.12

These were the most productive years of his output and it saw him working for short periods in Emilia Romagna, moving between Parma, Bologna and Carpi, attending to the numerous commissions for altar-pieces he had there.

After 1515, in which the art world witnessed the early death of Giorgione after having fallen under the spell of his unmistakeable style, and while Bellini’s work was revitalising his language with Il Festino degli Dei, and the sensual colours of Titian triumphed with his Assunta dei Frari, Cima was tirelessly reproducing these gentle and sublime formulas of his.

The last documentary evidence we have for him is in 1516 in Conegliano, when he submitted his tax returns. He died sometime between October 2nd 1517 and November 1518, dates which have been estimated based on his last two known certified documents.

Translated by Philip Rham