Link between serotonin and depression is a myth, says top psychiatrist

April 23, 2015

Brussels: The New Arts Capital of Europe?

April 25, 2015The artist Erwin Wurm is at the forefront of revolutionising the concept of contemporary sculpture, transgressing the rules of form and time.

By introducing humour and cynicism to his work, he appeals not only to an elite but also attracts a much wider public and the media. However, beneath this veneer of apparent lightness and fun, lies the depth of character of a man who fundamentally questions the values of the society we live in, and tries not to take himself too seriously.

A

As soon as you drive through the iron gates opening onto the landscaped gardens of Erwin Wurm’s estate, set in the flat open countryside of Lower Austria, you enter a secluded and peaceful world. His sculptures of gherkins, of a life-sized man clad in a pink suit adorn the meticulously kept garden of Schloss Limberg which serves as home as well as work place to the artist.

[sz-youtube url=”http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yRF0bB6I2Lw” caption=”Reya von Galen Interviews Erwin Wurm” margintop=”0″ marginright=”0″ marginbottom=”0″ marginleft=”0″ /]

Austrian born Wurm, father of two grown-up sons from a previous marriage and of a three-year old daughter by his second wife, is considered the leading living artist in his native country and regularly ranks among the top contemporary artists of our time in international art listings. Prices for his sculptures have soared accordingly over the last decade. Since his One-Minute-Sculptures propelled him to fame in the early nineties, his ideas have infiltrated and inspired popular culture. His concept of art as an ephemeral and transitory moment in time has expanded the boundaries of our definition of sculpture. Fat cars driving up walls, fat houses, square headless bodies, tableaux vivants of bananas sprouting from different parts of the human body, of pens and pencils growing out of nose, mouth and ears all form part of Wurm’s surrealist universe embracing the banal and the absurd with entertainingly provocative lightness of being. His Narrow House famously made headlines and heads turn at the Biennale in Venice in 2011. Wurm, born in 1954 in Bruck an der Mur, constructed it as a facsimile of the home he grew up in.

Erwin Wurm, Performance – Grammaire Wittgensteinienne de al culture physique – at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris Pantin, March 2013

It stands in stark contrast to the château he now inhabits with his family. Here Wurm has created a retreat for himself, surrounded by his own art and by his private collection: Joseph Beuys, undoubtedly the strongest influence early on in his career; Alighiero Boetti; Lucio Fontana; Elaine Sturtevant alongside a Dürer and a Picasso; works by fellow Austrian colleagues Brigitte Kowanz, Herbert Brandl, Martin Walde, Markus Schinwald, Josef Kern and Franz West displayed next to tribal art forming an eclectic mixture, a far cry from his middle class background and its symbols of narrow-mindedness.

Erwin Wurm: The Narrow House was my parents’ house, I helped my father build it. My father was a policeman, he didn’t have much money. It’s a typical Austrian house of the seventies, it has this pre-fabricated, industrialised form, a really awful architectural language. But that’s the architecture of our time and these houses are more and more destroying our landscape, our psychological and philosophical landscape.

One Minute Sculptures – 1997

45 x 30 cm | c-print | Photo Studio Wurm

Courtesy Xavier Hufkens Gallery, Brussels, Belgium

Reya von Galen: Is your art rooted in your childhood?

EW: It’s definitely rooted in the past in Austria. I grew up in the so-called little bourgeois society. Narrowness does not only mean my family, it means the society in the fifties, sixties, seventies in which I grew up in Austria. Post-war, post-nazi, still nazi, post- monarchy still. When you are part of the society, you inhale it, you grow into it, so it’s difficult to explain. In my work I can escape. A door through which I can escape is cynicism and humour because it’s like a tool, I can address very serious matters, very serious questions with this tool though it’s not the only tool I have.

Untitled (Franz) 5 – 2012 89,5 x 59,8 cm | acrylic on c-print Photo Studio Wurm

Courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Salzburg (A), Paris (A)

RvG: How seriously do you take yourself, how seriously do you take others and how seriously do you expect others to take you?

EW: Basically I take people seriously and I take myself seriously up to a certain point. I’ve learnt that the ability to be able to laugh about my own stupidity or about someone else’s stupidity makes it easier to accept you have a problem; accept things which we want to hide, such as embarrassment or ridicule; or hide the fact that we feel small and little in comparison to all these other grand people; or come to terms with personal tragedies.

I found it better to be able to laugh about these things than to take them too seriously – which would pull me down.

RvG:

Your look on life is always accompanied by a certain humour?

EW: I try to but it’s very difficult. When I think about Austrian politics or European politics over the last decade, I sometimes lose my sense of humour.

The Anarchist (Hermès) – 2008 150 x 112 cm | c-print Photo Studio Wurm Courtesy Xavier Hufkens Gallery, Brussels, Belgium

RvG: But you are one of the rare people who would have the opportunity to live somewhere else.

EW: For many years I thought about this question. I lived in New York for one and a half years and I lived in Berlin a little. But I grew up here in Austria, I was born here. My roots are here and then my friends are here and my family is here, so where should I go? At my age, any age I think except when you’re very young, it’s difficult to make real friends. That’s one of the reasons why I felt lonely in the States. Every weekend I went to the Metropolitan Museum to visit European Art. I like Europe as an idea very much.

RvG: Do you have to feel comfortable and happy and secure in your relationship with your family and friends to be able to work? There are artists who, on the contrary, need to suffer in order to be creative.

EW: At first, I thought this is 19th century romanticism, the idea that you need to suffer and to have had a big drama in your life in order to create something. But I’ve learned since then. Something very bad happened in my personal life and history, something really, really bad and for a very, very long time I was paralysed, almost for two, three years. After that I started with the One-Minute-Sculptures which brought me my success. So, now I look on this issue from a different angle. Before I had the feeling, here I am, the little artist and over there is this kind of higher level where all the great artists are with their philosophies and their theories and I could never connect. There was no link in a way. After this big tragedy in my life, I didn’t care about these things anymore and all of a sudden something happened which made it flow, which made it fluent.

Fat Convertible – 2001/2005 130 x 469 x 239 cm | Material: car, styrofoam, polyester. Photo Xavier Hufkens Gallery, Brussels, Belgium. Courtesy Xavier Hufkens Gallery, Brussels, Belgium

RvG: There is the element of fun, a comic resonance, even slapstick in your work, especially in the One-Minute-Sculptures or the 59 Positions which makes your work accessible to a very wide public. Is this something you endorse?

EW: It happened. I can’t say I was looking for it. Sometimes I use the language of science fiction and the language of comic strips and I mix it up and it seems to be easily accessible. Everybody sees a fat car. Easy to understand people think, that’s it and then they walk away. If you don’t walk away, if you stay, and you look at it more closely, then you see different layers, different perspectives, an existential philosophy, a psychology behind it. To begin with, as an artist, I yearned for my teachers to accept my art, or for other colleagues, big curators, museum directors or galleries to recognise my work. But I soon realised that the first standard in judging my own work was myself, I have to be satisfied.

RvG: Are you satisfied with your work?

EW: I’m mostly not satisfied with my work. I mean I’ve done some pieces of which I think they are ok and I like them. But then with the next pieces you want to be at least as good as with the previous one, or better.

RvG: Is there a piece of art of yours you would never sell?

EW: Yes, I destroy them.

RvG: I mean never sell it because it’s so close to your heart.

EW: No.

RvG: You would sell anything, everything?

EW: Yes. I sell them because I want them to be out in the world for other people to see them, it’s much more important.

RvG: You come across very much as a child of our times, reflecting the zeitgeist, in touch with the media and famously the Red Hot Chili Peppers cited you as their inspiration for their music video Can’t Stop in 2002. You have also crossed the borders to other artistic domains. You collaborated with Hermès, you made a style shoot with Claudia Schiffer reliving the One-Minute-Sculptures for Vogue. How would you define your relationship with the media?

EW: I find that the contemporary public space for art is the media. I accepted invitations from magazines, television, pop groups to connect my work with these things. When I created the One-Minute-Sculptures, I doubted whether they were good or not. Then all of a sudden I got this feed-back from all over the world from fashion photographers and designers who said: “Your work is very influential in this field and many people know your work and use it.” I realised all of a sudden that many advertisements based themselves on my ideas. I also realised many people misused the work, and for a moment I thought maybe I should do advertisements myself in order not to end up being the follower of my own work! With Hermès I said yes because I am interested in working on the themes of our time: the beauty cult, the youth cult, the question of being fat or not: socially relevant questions which touch many people; and finally the subject of icons, an invention of the 20th century. And Hermès is a fashion icon. They didn’t ask me to make an advert, they invited me to reflect through my work about Le Monde Hermès, and that’s what I did.

Wall Sweater, 2011

Material: canvas, wool. Reya von Galen and Erwin Wurm. Photo: Florian Hatwagner

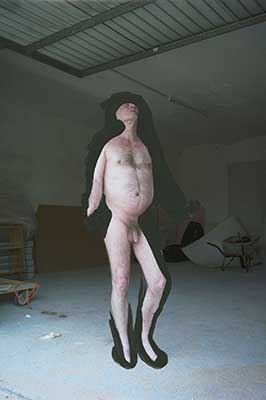

RvG: One of your last exhibitions was entitled De Profundis: you photographed men of a certain age, naked, and then partly painted over the picture. The work seemed far away from your usual humour. Has your art matured?

EW: In the 11th, 12th and13th centuries the body had little significance, the important thing was the soul. Pain and death were more accepted than nowadays. We hide pain, we hide death and we hide ageing. There is a whole industry to avoid age. We all do it and we all like doing it because we have succumbed to the youth cult. I found myself ageing and I wanted to create certain positions of the bodies reminiscent of former positions of the Renaissance or of the Gothic era. All the men pictured are friends of mine, my friends are the same age as I am or a little older or a little younger, men past their prime, and this interested me.

18 Pullover – 1992

50 x 70 x 25 cm | Material: 18 pullover

Photo Studio Wurm

Courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac,

Salzburg (A), Paris (A)

RvG: So it’s also a self-reflection?

EW: Absolutely. In advertisements you see only young people, young beautiful women and beautiful men. Nobody shows older people, and I found it so interesting to see these bodies and to also be able to see their genitals, not functioning, I mean functioning but not in function obviously, so you see a totally different attitude in these men. I used paint as a cultural tool to transform or deform the body into something else.

Getting old and transferring the body from this so-called youth-concept to something else, that’s what I found great.

RvG: Age and death are on your mind?

EW: Yes. Next year I’m sixty years old.

RvG: Is there life after death for you?

EW: Only through art and through children.

RvG:

You are at the pinnacle of your career. Do you enjoy your life?

EW: Yes. I enjoy my life very much. I’m a so-called happy person although every day I’m fighting with my work. And this sometimes is a real pain. Sometimes I hate it. Because I always have the feeling I have no ideas anymore, nothing. So I constantly have to prove myself anew. I’m my own torture chamber.

Untitled (Claudia Schiffer) – 2009 114 x 144 cm | c-print Photo Studio Wurm. Courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Salzburg (A), Paris (F)

RvG: What is your assessment of the art world, the industry behind it, the fact that there are a handful of influential galleries, collectors and curators who dominate the art market, distorting it by holding back works of art or threatening to put the entire work of one artist on the market. It is rare that the artist himself may be in a position to manipulate the market, like Damien Hirst is able to. How do you relate to that?

EW: If I were English or American my prices would be ten times higher. The English were always much smarter than the rest of Europe in getting the rich people to come to see and buy their work.

RvG: I’ve mentioned Damien Hirst because he’s an artist who successfully plays the markets. You go to see one of his shows and there’s a whole mechanism behind it: you can get the T-shirt and the book and the badge and the pen, the whole thing.

EW: Damien Hirst is a genius in this. He’s really a genius.

RvG: A genius as an artist or as a marketing manager?

EW: He’s also a very good artist. Very often he was despised because he’s addressing certain ideas and certain issues about the market but I found it brilliant. There are many artists who envy his success.

Narrow House, 2010

(Bathroom)

RvG: Talented artists are being overlooked because they don’t fit into what the collectors happen to be missing in their artistic portfolio.

EW: Sure. It’s unfair, and it’s a drama and it’s unrealistic and as Gerhard Richter once said it’s vulgar. It’s obscene to pay insane prices.

RvG: Are they justified in any way?

EW: It’s justified by the people who buy it. It’s pure capitalism. But we’re not talking about quality. We’re talking about prices. Quality and prices must not go together. There is an artist, I won’t say his name, he’s an English artist, an older guy, a painter, I found his work horrible, but he has insane prices. I don’t envy him, but according to my taste, I don’t understand it.

RvG: Can anybody be a definitive judge of art?

EW: I’m not able to judge and that’s also the reason why I gave up my professorship at university, because there are a hundred million different opinions about something. In the past you knew exactly what was supposed to be good. Now it’s totally different and totally free and many opinions are acceptable.

RvG: You collect work of other artists.

EW: Yes. I collect things I like. Things I really like.

RvG: You don’t think about the investment?

EW: Well, I must confess, sometimes I think about the investment because I buy it not only for myself, but also for my children.

RvG: What would you like to be remembered for? Will you be remembered for your work?

EW: I can’t say. I think it would be vain for me to say. I’ve learnt that everything is so relative and everything changes so quickly and taste also changes so quickly. It would be nice if my children can say he was a nice man and a lovely father.

Narrow House – 2010

7 x 1,3 x 16 m | mixed media. Photo. Studio Wurm. Courtesy: Installation view at the 54th. Biennale di Venezia, Gallery Thaddaeus, Ropac, Paris, France; Gallery Xavier. Hufkens, Brussels, Belgium; Lehmann Maupin Gallery. New York, USA

This summer, Erwin Wurm is due to receive the Grand Austrian State Award presented by the Ministry of Culture, awarded by a committee of past recipients famously including Elfriede Jelinek, Peter Handke and Thomas Bernhard. The latter, however, refused to accept the prize during the actual ceremony, feeling insulted by the minister’s speech in his honour – a scandal Erwin Wurm, though no stranger to cynicism and the breaking of taboos himself, is unlikely to provoke. To the attentive observer, the critical eye Erwin Wurm occasionally casts on his country may be an echo of Bernhard’s cynical spirit but barely disguises the deep feeling of belonging to his Austrian origins palpable both in his words and in his actions.

[note]

Erwin Wurm’s current exhibition / performance Grammaire Wittgensteinienne de la culture physique is on show at the Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac in Pantin/ Paris.

A dramatic text written by Wurm – he refers to it as a performative sculpture – will be staged by Matthias Hartmann, the director of the Vienna Burgtheater on July 25th 2013 as part of the 30th anniversary of the Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac in Salzburg.

[/note]