The final days of the burning man festival.

September 4, 2015

Sex in Mao’s Time and Today

September 11, 2015In a review of Manfred Zylla’s latest book, German critic Andrea Schlaier noted that Zylla’s paintings suggest that the lust for cruelty is inside all of us. The 77—year-old German/South African artist does not disagree, and even points out that it was not the focus of his series, 120 Days of Sodom. However, the 120 paintings which took the artist a year to complete, are arguable his most transgressive work since the 1980s.

by Heidi Rasch

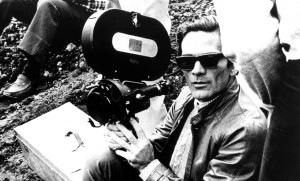

While the works are influenced by the writings of Dante Alighieri and the Marquis de Sade, it was Italian filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini’s last-made film Salò which provided Zylla with his primary inspiration. In recontextualizing the series into book form, Trevor Steele Taylor was the artist’s first choice as leading essayist. Taylor had met Zylla in South Africa during the 1980s and he was familiar with Zylla’s history and work as a resistance artist. But it was Taylor’s own history which singled him out as the most suitable writer for the kind of crossover art/cinema publication that was envisaged. Here we had a consummate film connoisseur known as the champion of the alternative, non-conformist, eccentric and often obscure film practitioner. Taylor is the film curator who programs his festivals with the gems of cinema found on the deep outskirts of the non-mainstream, films either forgotten or considered too controversial.

While the works are influenced by the writings of Dante Alighieri and the Marquis de Sade, it was Italian filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini’s last-made film Salò which provided Zylla with his primary inspiration. In recontextualizing the series into book form, Trevor Steele Taylor was the artist’s first choice as leading essayist. Taylor had met Zylla in South Africa during the 1980s and he was familiar with Zylla’s history and work as a resistance artist. But it was Taylor’s own history which singled him out as the most suitable writer for the kind of crossover art/cinema publication that was envisaged. Here we had a consummate film connoisseur known as the champion of the alternative, non-conformist, eccentric and often obscure film practitioner. Taylor is the film curator who programs his festivals with the gems of cinema found on the deep outskirts of the non-mainstream, films either forgotten or considered too controversial.

In a recent interview Taylor notes that: “Zylla comes to de Sade through a relationship with the lens of Italian filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini. Pasolini is probably the most directly political of filmmakers. That said, he is also the most spiritual; a Marxist with deep understanding of the message and the journey of Christ, and a homosexual who glorified the natural energy and innocence of sexuality in its widest meaning.”

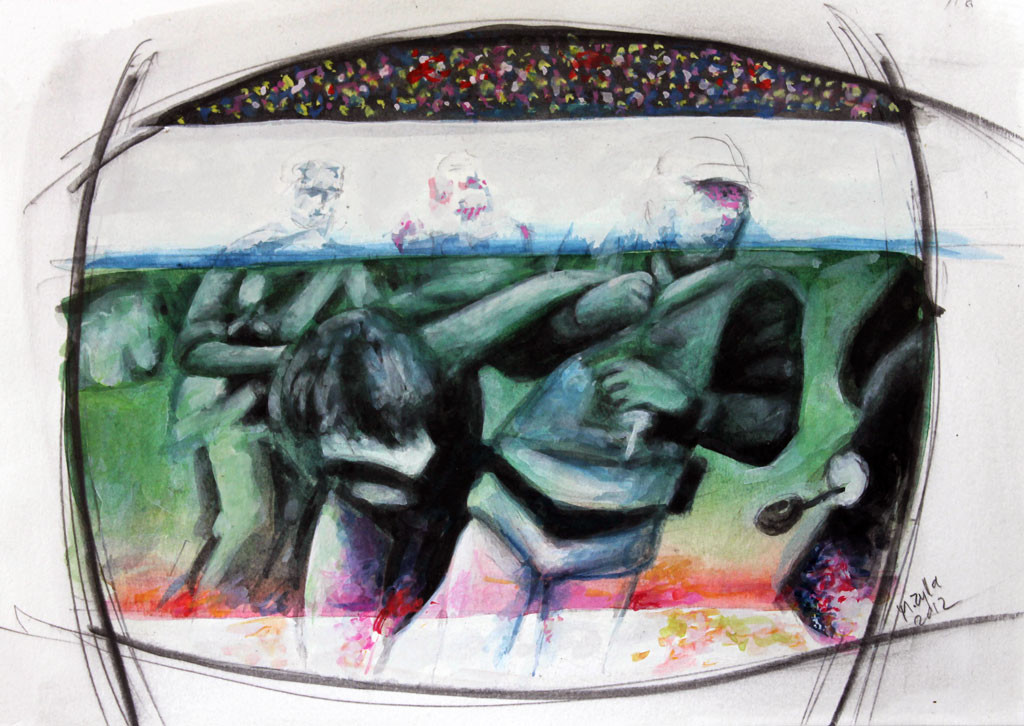

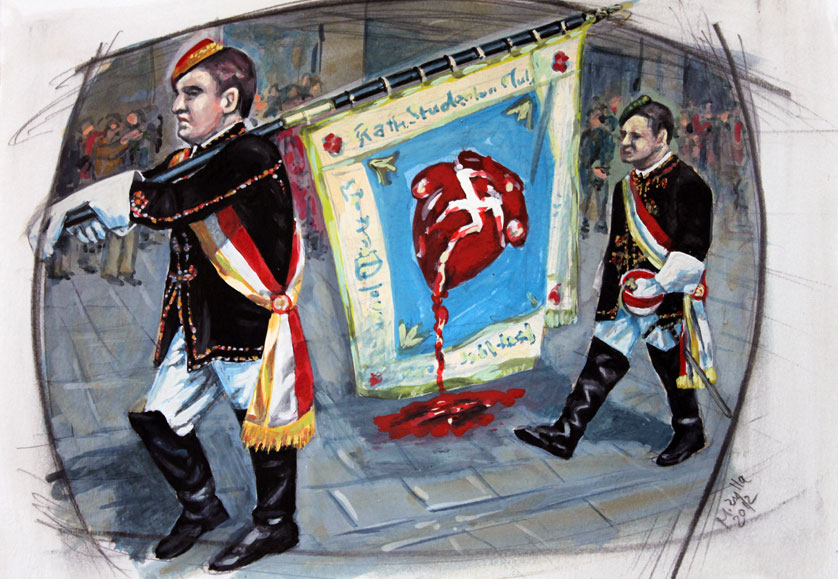

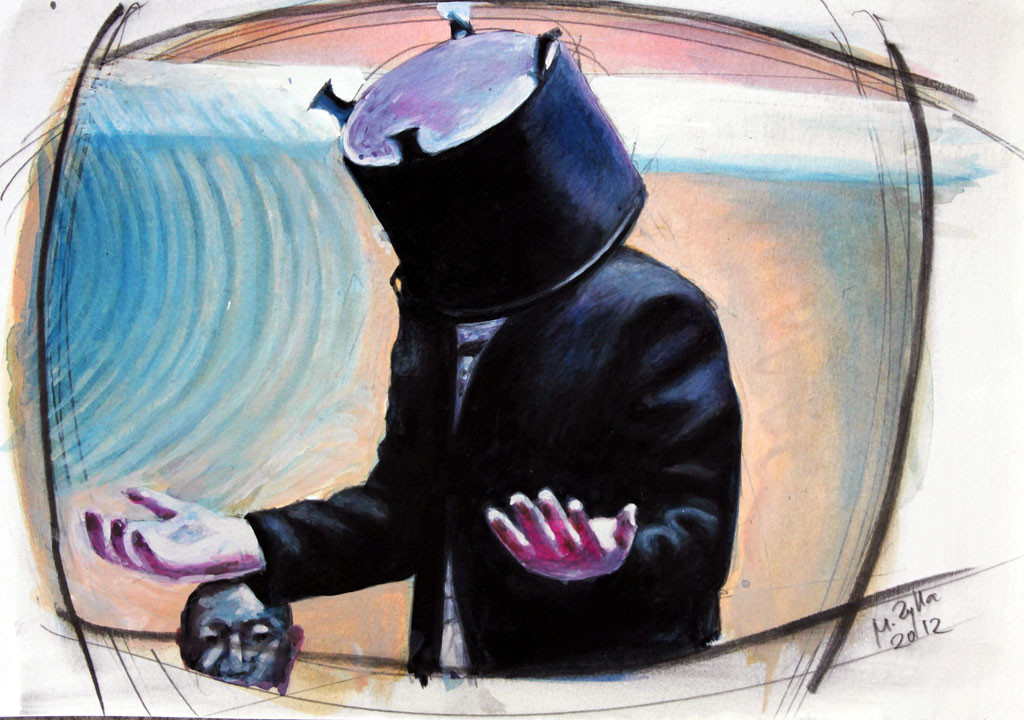

According to Taylor Pasolini’s final film, Salò is: “cinema on the very edge of the abyss. Sade’s book concerns a group of libertines (representing power in the form of religion, politics, finances and governance) who, through their wealth, kidnaps a group of the children of the rich to fulfill, through a series of ritualistic orgies, their depraved desires. Pasolini reset the events in fascist Italy in the last months of the war, with the same pantheon of power brokers now gorging their cruelty and lust for power on the kidnapped children of the proletariat. Zylla’s series of paintings vary between direct representations of frames from Pasolini’s film as well as side references to modern consumerism, nuclear immolation, the rape of Gaia (fracking) and militarism (the military-industrial complex).”

Zylla has said about the series: “As a painter I wanted to immortalize particular scenes from Pasolini’s film by making small and intimate paintings. I used the outline of a screen to frame these scenes and Pasolini’s cast of characters. I wanted to disrupt the original context and settled on a non-sequential sequence in the series. I wanted each painting to own its own narrative. My paintings are not film stills -– they bear the burden of my intricate brushstrokes. Collectively the series acts as homage to Pasolini, but perhaps also reflect the world today — in all its brutality. A world gripped, trapped and slowly being suffocated by a lust for power and desire to consume. That is the vision I share with Pasolini. In the book I relied on multiple voices to comment on the main threads of the series. I have not worked with writers in this way before, but throughout my career I have included text in most of my work, I have collaborated with fellow artists both in South Africa and in Germany, and probably my most memorable collaborative project was when I invited my local community to alter my artworks.”

In addition to Taylor’s essay, the book also includes text submissions by 31 writers drawn from a variety of backgrounds, nationalities and professions. The writers were briefed to not reference Zylla’s artworks but instead focus on the contemporaneity of the three main influences. It was not only Pasolini’s legacy as a filmmaker which creates the bridge between the visual and written sections but also his influence as poet, and his strong views on language. Mother tongue submissions were thus favoured and writers were limited to a word count; an intentional stripping of explicatory detail. The linkage to cinema continues in the text section with the inclusion of two excerpts from film scripts, the voice of an actor and a reference to music, through the lyrics of COIL.

Once printed and bound, the visually rich 120 Days of Sodom Manfred Zylla developed into a publication which is difficult to categorize; as an art book it has found its way onto the book shelves of art museum libraries; the text content has taken the book into some of the world’s leading research libraries and its rich cinema content has secure its arrival at several film libraries and institutes.

120 Days of Sodom Manfred Zylla is published by ErdmannContemporary in Cape Town, South Africa.

Text by Trevor Steele Taylor, Aryan Kraganof, John Peffer, Chris Pretorius, Alessandra Atti Di Sarro, Professor John Higgins, Nicola Roos, Ludwig Binge, Antonín Mareš, Marlene Le Roux, Dr Nomusa Makhubu, Andrea Dicó, Niklas Zimmer, Caspar Greeff, Ivor Powell, Rafael Powell, Tim Leibbrandt, Pablo Cesar, Andrea Tapper, Stephen Thrower, Dr Ludmila Ommudsen Pessoa, Professor Rozena Maart, Erik Chevalier, Ashraf Jamal, Carsten Rasch, Hofmeyr Scholtz, James Matthews, Garth Erasmus, Cheng Qian, Cheng Haotian, Usen Obot & Paul Valentine.