How the virtue of greed is destroying ‘our common home’

September 24, 2015

Dante Recommends “Seven Songs for a Long Life” A movie with its heart in the right place

October 5, 2015One question: is the UK economy going to be safe in the hands of Jeremy Corbyn? That obviously assumes that the new leader of the Labour Party will get a chance to make his mark, be in post to fight an election and to win it. Certainly, though, people are asking about his views – with his supporters saying he has opened a window towards a resurrection of the economy in the United Kingdom. The economist Steve McCarthy comments on the first few days of the new Labour leader and on the potential for a radically orthodox economy.

by Steve McCarthy

The rate of investment in Britain, at about 15% of GDP, is among the lowest in the world. In France, for instance, it is 22% – half as big again. The difference shows. Labour productivity is higher in France than in the UK, which is turning into a low wage economy. Successive British governments look for quick fixes, magic bullets, to raise the level of productivity. But there is no quick fix. It is the largely the result of very low levels of public investment over many years, as well as of poor technical education.

When a quarter of a million people voted in the election on the 12th September for Jeremy Corbyn, the rank outsider, to become leader of the Labour Party and therefore Leader of the Opposition in the House of Commons, the poor quality of Britain’s infrastructure was certainly not their main source of discontent. Rather they were concerned about the government’s austerity programme. But the two issues are linked, as we shall see later. In fact Corbyn’s supporters are part of a growing movement, sweeping across Europe, encompassing Podemos in Spain and Syriza in Greece, and even extending to Bernie Sanders’ supporters in the US Presidential election, of those who have become disillusioned with the established political parties, with their policies that impose austerity on the poor and vulnerable while systematically supporting and rewarding bankers and businesses, and with the cronyism and corruption that permeates the whole political establishment. As we all know by now, Corbyn won by a landslide – almost sixty percent of Labour Party Members and supporters – to the utter consternation, even hostility, of many of his fellow Labour MPs.

Since then he has been mocked and vilified by the Tory government and most of the British press, and portrayed as someone who holds hopelessly unrealistic, old-fashioned and even dangerous views on economic policy. And, to put it mildly, Corbyn has not found much support among his fellow (New) Labour MPs who had failed to catch the changing political mood, having been content hitherto to respond ‘me too – maybe’ to the various immoral and socially destructive policies of the Tory government.

But Jeremy Corbyn’s economic views are thoroughly orthodox and realistic. It is the policies of the present government, namely of Cameron and Osborne, that have no solid economic foundation and are in fact an economic disaster, as many economists, including Nobel Prize winner, Paul Krugman, have pointed out. Writing in the Guardian on 29th April 2015, just before the general election, Krugman wrote:

I don’t know how many Britons realise the extent to which their economic debate has diverged from the rest of the western world – the extent to which the UK seems stuck on obsessions that have been mainly laughed out of the discourse elsewhere.

The place to start is Corbyn’s opposition to the government’s austerity programme. A national economy is not like a household budget which, in a recession, may have to be cut back to avoid more borrowing, though that seems to be the model in Chancellor Osborne’s head. The opposite is the case; the orthodox economic response in recession is for governments to stimulate the economy by increasing their own spending. The worst policy response is to drive the economy deeper into recession by cutting services and benefit payments for those at the bottom of the income scale while reducing the tax burden on the rich. Such a policy is especially perverse since the recipients of benefits actually spend their income, which then goes back into the economy, while the rich have a large propensity to save. Even the International Monetary Fund (IMF), usually considered as rather conservative, has debunked this nonsense. And indeed it’s been shown not to work since Osborne has had to change the timetable for moving into surplus as tax receipts were lower than expected, despite all the boasting about employment going up. Nevertheless, pursuing such perverse policies is what the government has done, and is still doing This suggests that its real agenda is something different: to achieve a fundamental shift in the state’s relationship with citizens, without caring at all about how many millions of people they drive into poverty as a result, or about the risk of social breakdown as a result of rising inequality. The excuse used is that such policies will inspire business confidence and encourage private investment in more jobs. But, as Krugman writes: ‘Business leaders love the idea that the health of the economy depends on confidence, which in turn – or so they argue – requires making them happy.’

The place to start is Corbyn’s opposition to the government’s austerity programme. A national economy is not like a household budget which, in a recession, may have to be cut back to avoid more borrowing, though that seems to be the model in Chancellor Osborne’s head. The opposite is the case; the orthodox economic response in recession is for governments to stimulate the economy by increasing their own spending. The worst policy response is to drive the economy deeper into recession by cutting services and benefit payments for those at the bottom of the income scale while reducing the tax burden on the rich. Such a policy is especially perverse since the recipients of benefits actually spend their income, which then goes back into the economy, while the rich have a large propensity to save. Even the International Monetary Fund (IMF), usually considered as rather conservative, has debunked this nonsense. And indeed it’s been shown not to work since Osborne has had to change the timetable for moving into surplus as tax receipts were lower than expected, despite all the boasting about employment going up. Nevertheless, pursuing such perverse policies is what the government has done, and is still doing This suggests that its real agenda is something different: to achieve a fundamental shift in the state’s relationship with citizens, without caring at all about how many millions of people they drive into poverty as a result, or about the risk of social breakdown as a result of rising inequality. The excuse used is that such policies will inspire business confidence and encourage private investment in more jobs. But, as Krugman writes: ‘Business leaders love the idea that the health of the economy depends on confidence, which in turn – or so they argue – requires making them happy.’

Of course it makes it easier if you simultaneously launch a, sadly very effective, propaganda campaign through the media to vilify those dependent on benefits as lazy ‘benefit scroungers’. As Mr. Corbyn said to Labour MPs on 15th September 2015: ‘Austerity is actually a political choice that this government has taken and they’re imposing it on the poorest and most vulnerable of our society’.

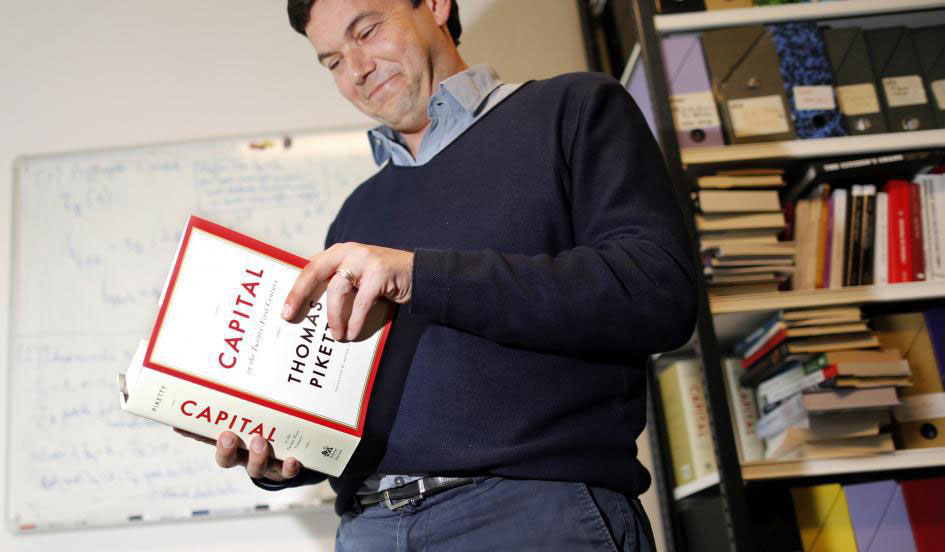

Corbyn’s alternative to austerity as set out in his pre-election manifesto has two principal themes. The first is to make various taxation changes that would have a particular impact on those who are more prosperous but who currently pay proportionately less taxes than many of the poor. It is not a fully worked out programme, but it could include increases in corporate taxes and measures to avoid avoidance and evasion; increasing the marginal rate of income tax for those earning more than £100,000 a year; lowering the threshold for inheritance taxation; and introducing a wealth tax as Thomas Picketty advocates in his best-selling tome: Capital in the Twenty-First Century.

Such proposals are of course derided by the political establishment including New Labour politicians, with the retort that they would merely drive businesses, who supposedly create the jobs – so called ‘wealth creators’, abroad. Actually, although there would be much grumbling and dire warnings about economic collapse, there’s no actual evidence that entrepreneurs have to be offered high monetary incentives in order to keep them working; it’s in their blood. As Krugman pointed out above, this is a myth that the prosperous have created to serve their own interest. A generation ago businesses flourished even when bosses were paid only ten times as much as their workers; now we are given to believe that they have to be paid a hundred times as much, or even more. Other European countries, notably in Scandinavia, seem to have done just as well as Britain without such a gross distortion of the wage structure.

The second theme, in Corbyn’s manifesto, is to increase the rate of public investment in infrastructure, housing and renewable energy, which brings us back to where we began. The Conservative government has tended to abdicate its responsibility for public investment believing that this can largely be left to the private sector. But much infrastructure investment only shows a return over a long period of time and so long as other infrastructure investment takes place in parallel or in a planned sequence. The private sector cannot provide this; it invests for the short term. Thus Corbyn’s proposal to create a National Investment Bank, for this purpose, is a highly orthodox economic proposal. Such a bank is a way of bringing private sector finance into publicly owned infrastructure without it being on the government’s own books nor without the state losing ownership or control of the investment programme. There are many such examples across Europe. The KfW in Germany has been investing in such a way since the end of the Second World War and is now a major financial institution described by Global Finance in 2014 as ‘the safest bank in the world’. At the European level, the European Investment Bank, which is about twice the size of the World Bank, serves the same purpose. Similarly Corbyn’s proposal that two great national networks – the railways and the power sector – should be taken back into public ownership may appear old-fashioned but is not necessarily radical. France and Germany both run highly effective railway systems in public ownership and Electricité de France (EDF) owns most of the electricity generation and transmission infrastructure in that country. Yet again it is not Corbyn’s proposals on infrastructure that are unorthodox but rather the Conservative government’s blind faith in private investment which is now undermining Britain’s long term prosperity. Writing in the Guardian on 19th August 2015, Lord Robert Skidelsky, the world’s leading expert on Keynes, said:

Corbyn should be praised, not castigated, for bringing to public attention these serious issues concerning the role of the state and the best way to finance its activities. The fact that he is dismissed for doing so illustrates the dangerous complacency of today’s political elites. Millions in Europe rightly feel that the current economic order fails to serve their interests. What will they do if their protests are simply ignored?

Corbyn should be praised, not castigated, for bringing to public attention these serious issues concerning the role of the state and the best way to finance its activities. The fact that he is dismissed for doing so illustrates the dangerous complacency of today’s political elites. Millions in Europe rightly feel that the current economic order fails to serve their interests. What will they do if their protests are simply ignored?

The creation of a National Investment Bank should be considered on its own merit. Corbyn makes an additional proposal that it could be financed by redirecting the Bank of England’s programme of ‘quantitative easing’ – in effect printing money – to this end rather than towards the commercial banks. This idea has been given the alluring name People’s Quantitative Easing. But whether the two proposals should be linked and whether the economy now needs further QE is up for discussion. If it does, then People’s Quantitative Easing should perhaps be designed differently. Martin Sandbu, writing in the Financial Times on 14th September argues that ‘it would be much better for money-printing to be channelled directly to households and for the government to raise revenues the old-fashioned way’.

This, in the FT indeed, is actually a more radical idea than that of Corbyn’s own advisers!

Thomas Picketty’s extensive studies on the matter show that inequality in the distribution of income and wealth in Britain, as well as in other countries, is now as great as it was just before the First World War. This is simply grotesque and is already causing social breakdown as more and more people no longer have secure affordable housing and have to resort to food banks in order to survive from one day to the next. In a prosperous society, such as Britain is, it is simply an outrage that this should be the case. A generation ago we may have imagined that Dickensian slums were a thing of the past, but they are returning. Sadly too many in Britain have been taken in by the myth, carefully created by government propaganda, that ‘hard working’ people are up against the ‘benefit scroungers’. Nor do most realise that at some time or another a significant minority of the ‘hard working people’ will find that they need support from the benefits system, for a least a period of their lives, perhaps because of unemployment or illness, and will thus themselves become ‘benefit scroungers’. Yet we still support such policies – well actually a few of us do, since the current government was elected by just a quarter of the electorate. Perhaps the fundamental problem is how few people really understand the extent to which Tory policies systematically favour the rich – the few percent of people at the top of the income scale.

Shortly before his election as leader of the Labour Party forty two economists wrote a joint letter to the Guardian, saying, although they were not all ‘supporters of Jeremy Corbyn, nevertheless:

His opposition to austerity is actually mainstream economics, even backed by the conservative IMF. He aims to boost growth and prosperity […] despite the barrage of media coverage to the contrary, it is the current government’s policy and its objectives which are extreme.

How effective Corbyn and his team will be in putting across orthodox economics to a brain-washed public remains to be seen. But it is the sort of policies that he is advocating, and not those of the present government, which would maintain the prosperity of the British people and support a cohesive society.