120 Days of Sodom Manfred Zylla – from series to book

September 8, 2015

Dante in London

September 15, 2015The ultimate yin and yang: male and female. As yin and yang of west and east meet, George Walden explores how attitudes have changed in China.

by George Walden

In Shanghai recently, alone in the street for a few minutes while my wife was in shop, I was propositioned.

In Shanghai recently, alone in the street for a few minutes while my wife was in shop, I was propositioned.

In today’s China this is no big deal, nor is the service reserved for foreigners. Hotels used by ordinary Chinese swarm with prostitutes, not to speak of clubs and bars. I mention the incident because, to a veteran of the Cultural Revolution whose first image of China was one of virulent chauvinism and a pathological Puritanism, the idea of a pretty young woman approaching you in the street with a smile was still a little surreal.

Not far from the Bund, the old colonial quarter facing the river, three girls were at work under an arcade, and such is the force of custom that for a second the sight of them in a Chinese street made you feel priggish. Then you remembered how happy you were, not to see women selling themselves in public, but at the idea of a semi-normalised China which catered for human fallibility.

At least they looked friendly, these young whores, chattering and laughing and smoking away. Forty years earlier the sight of a long-nosed imperialist brazenly walking their streets risked putting women their age in a state of ideological frenzy. They would follow me with disgusted eyes, maybe spit some venomous slogan as I passed. Now, instead of being bawled out as an imperialist or revisionist swine (sometimes the Red Guards mistook you for a Russian), at 3:30 in the afternoon I was cheerfully accosted. (Minutes later a police car appeared, and the girls scampered off.)

Who were the women who stared at me with hostile faces forty years ago, and who were the hookers grinning and cajoling me now? Socially speaking they were probably the same people, from similar rural backgrounds. In the late sixties young people from the provinces wandered the country “making revolution”, which is to say sight-seeing, marching in demonstrations, loafing about, smashing up old temples, taking part in lynchings and “struggle meetings”, or beating up people whom someone had taken into their heads to denounce as anti-Maoist.

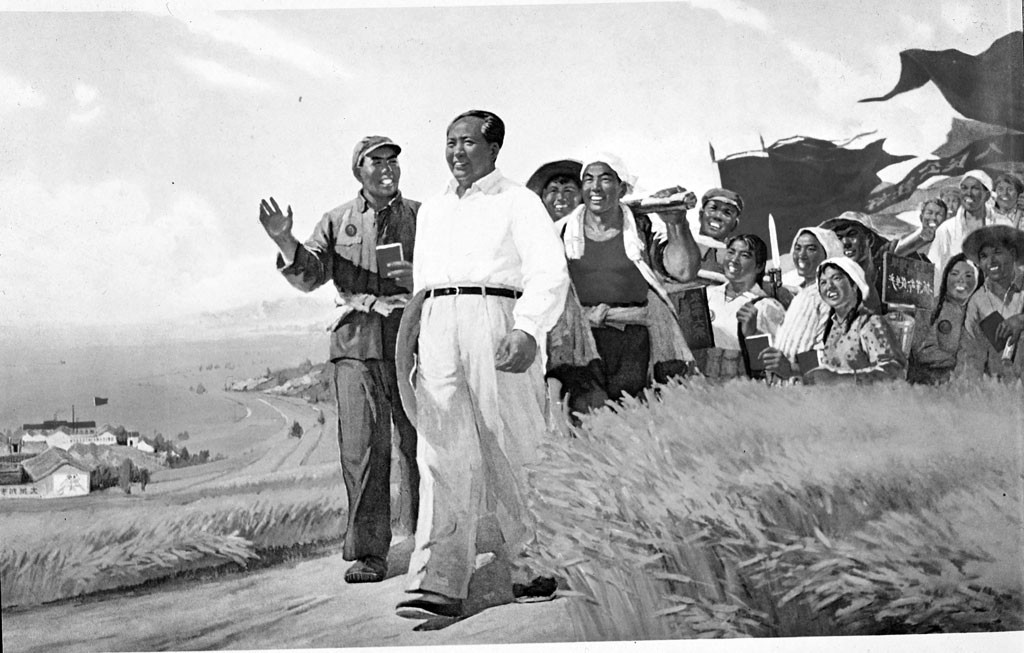

In Cultural Revolutionary days the traffic between town and village was two-way. While crusading provincials crowded the cities to no purpose, “bourgeois” students and cadres were despatched from town to deepest countryside to sanitise their thinking by humping night-soil or cleaning out pigsties. Seeing little purpose in that, most of them escaped back to the towns as soon as the political situation allowed. Mao had his despot’s reasons for re-familiarising townees with peasant life, of which they had a horror, but a stint in a godforsaken, poverty-stricken village in the middle of nowhere usually meant that their horror grew. The only lasting benefit appears to have been to literature, where the tribulations of rusticated intellectuals (and more occasionally claims of increased wisdom through contact with the peasantry) are a frequent theme.

I have seen the Red Guards compared in the West to adolescent pop fans on the rampage, but it wasn’t music that had got them going, nor was it drink or drugs. It was hate: hate, and the nihilism of violence. Years later, when people who had participated in all this viciousness and cruelty at such a young age were asked in a survey why they had done it, only a few replied that it was out ideological passion and devotion to Mao, or because they were forced to. Most said they beat people up because it was all right to do so, and because they enjoyed it.

Today the raw-looking, poorly educated men and women that can be seen exiting from mainline railway terminals are there for more pragmatic reasons. They are coming for work and in some cases, survival. The girls hawking themselves in Shanghai were three in a tide of an estimated 200,000,000 – a sixth of the Chinese population and nearly four times that of Britain – who have abandoned the countryside and roam the towns in search of jobs. The males amongst these gongmin (itinerant workers) find it easier to be taken on, mainly in the booming construction industry, even if the pay is the equivalent of a paltry £12 a week.

For women it can be harder: many who can’t find jobs in the factories or service sector gravitate into girly bars or prostitution – a major industry in itself. Others end up there after abandoning the struggle to live on the derisory wages unskilled women can be paid. Stories of how indigent young peasant mothers go to towns, leaving their child with grandparents, and after failing to find work resort to prostitution to send back remittances for their children’s education while disguising the source of the money, are part of the true-life Victorian melodrama produced by the greatest population displacement the world has seen.

As in the rest of the world, the primary use of the internet in China is for sex or games, something the regime may deplore but does little to discourage. Absorption in pornography and the proliferation of prostitution may be unedifying and against Chinese traditions of public chastity, yet from the regime’s viewpoint it is preferable to an unhealthy interest in politics. As readers of the mammoth 17th century novel Dream of the Red Chamber know (the original has 4,000 pages and 400 characters), the country has a healthy erotic tradition, though sexual prudishness predated the communist revolution. There would be more evidence of the extravagance and sophistication of Chinese erotica extant today had not the Emperor Kangxi (1655-1723), a cross between aesthete and Puritan, destroyed whatever traces he could find.

Historically, sex in China, as elsewhere, has its hypocritical side. While chastity was prescribed for ordinary people the Chinese upper classes, as ever, felt themselves exempt, and in communist times Mao Zedong exerted himself in the maintenance of this tradition – according to one of his doctors his preference appears to have been for virgins. As the Chinese saying goes, the rich can burn down houses while the poor are not even allowed to light lamps.

During the Cultural Revolution official Puritanism reached a zealous peak. Posters denounced alleged anti-Maoists for, amongst other things, “yellow” (indecent) practices, which so far as it might be true at all probably meant a partiality for harmless novels. Just as we worry about the mental balance of Saudi youths brought up on a God-struck, sex-free diet, it was hardly fanciful to see in the fanaticism and ferocity of Red Guard youths a reflection of their frustration in other fields. Kissing their girlfriends or boyfriends (had they been allowed to have them, or to kiss in public) would have been a more natural – and more productive – way to spend their time.

In one way, however, the regime inadvertently encouraged sexual excess. During a visit I made in the 1980s to China as Britain’s Minister for Higher Education, the Chinese Education Minister explained that he was obliged to run two schools in one building because the population explosion had left him with fifty million more children to handle. When I raised an eyebrow he looked surprised in turn: “You were here during the Cultural Revolution. You saw the closed factories and the people “making revolution”. What do you think they were doing when they weren’t marching about? Playing cards and sleeping with their wives.” In this period at least Mao’s puritanical revolution seems to have had the same results as an inordinately extended brown-out in New York City.

Even after the Cultural Revolution was over, a measure of sexual repression continued. In the 1980s an announcement on a prison notice board in Sichuan province described the crime of a new prisoner:

Lu, male, 25 years. Held private parties and danced cheek to cheek in the dark, forcefully hugging his female dance partners and touching their breasts. Seduced a total of six young women and choreographed a sexually titillating dance that spread like wildfire and caused serious levels of Spiritual Pollution. Execution imminent.

Today Chinese sexual habits are evolving fast in a libertarian direction. Anti-vice laws have become far more lax. In Chinese hotels notices prohibit prostitution, betting and drugs, but many are hives of all three, with an endless supply of inexpensive mingong girls volunteering – or being driven – to sell themselves. This reversal of Maoist prudery seems unlikely to be motivated by an attachment to individual liberties. As already noted the flourishing of prostitution in China – Hong Kong can seem tame by contrast – is remarkable and explained by many factors. First there is the abrupt release from much of the former system of control and surveillance of people’s daily lives. Then there is the desperation of mingong girls. One-child families, a policy which leads to a shortage of women as girls are aborted, also feeds demand. And finally there is the moral vacuum the collapse of Maoism brought in its wake, and the cynical pursuit of profits it has helped induce.

The doyen of Chinese sexologists (the discipline, though expanding, scarcely exists) Pan Xuming has investigated the phenomenon. His results support the theory of official tolerance bordering on connivance. Technically prostitution is outlawed, yet fines are so modest they act less as a deterrent than as a means of monitoring the trade, like a pimp’s payoff. Even the different levels of demand are semi-officially regulated: concubines for Taiwanese entrepreneurs, high-class call girls for Americans, Europeans and Japanese, and peasant girls for itinerant workers.

Then there are the students who, short of funds to pay for their courses, are ready to sleep with up-market clients. The phenomenon is not unknown in the West, but in China it is redolent of a new amorality. As one girl told Pan sardonically: “I am contributing to national development without consuming oil, which is rare in China, and without contributing to our pollution problem.”

There are limits to the CCP’s broadmindedness. An article in The People’s Daily in 2005 took solemn exception to the news that 95% of cadres found guilty of corruption had mistresses. It was pleased to announce that in one town the local government had taken the initiative in establishing a register of extra-marital relationships. “Always more creative in the struggle against corruption” ran the headline, which will have ruined many a top cadre’s day.

Adapted from “CHINA: A WOLF IN THE WORLD?”

Adapted from “CHINA: A WOLF IN THE WORLD?”

by George Walden published by Gibson Square Books. UK

Walden is a former U.K. diplomat and Conservative minister.