Yin and Yang in Music

October 10, 2015

London celebrates African culture in word, symbol and song

October 20, 2015Revealed for first time: Story of Hitler’s dealer and his looted art hoard

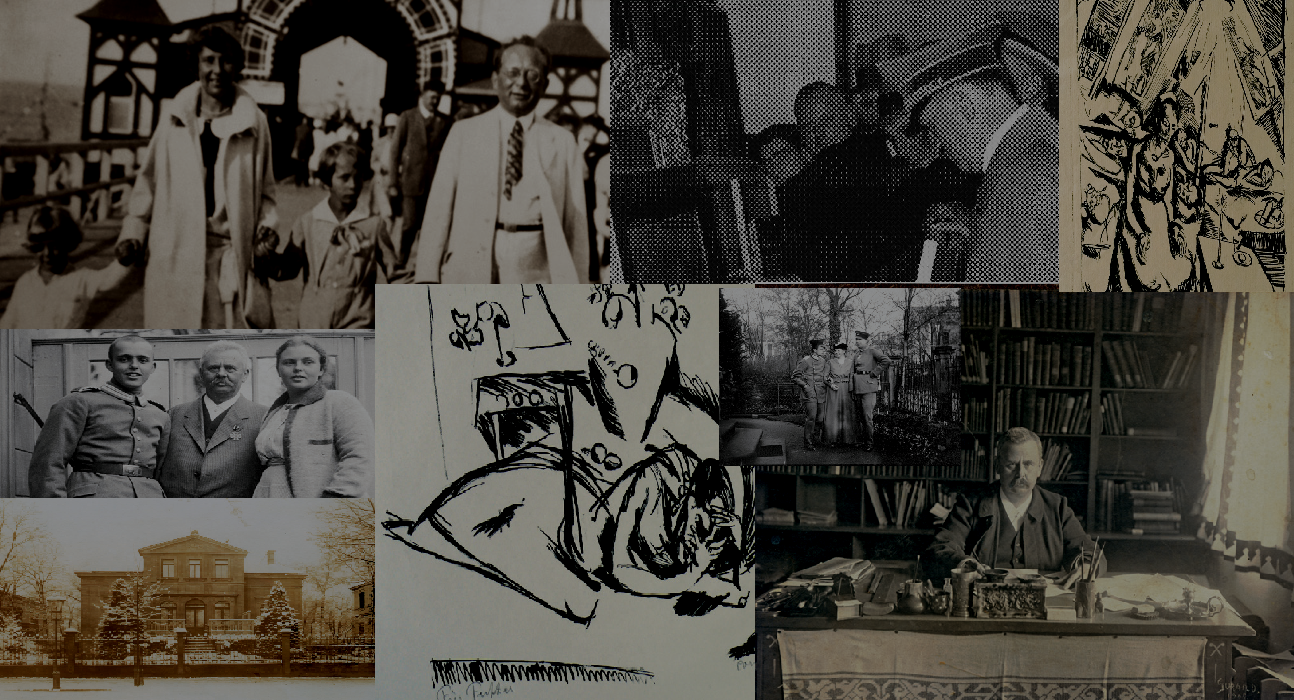

Images related to Catherine Hickley's book, The Munich Art Hoard: Hitler's Dealer and His Secret Legacy, published by Thames & Hudson.

By Mark Beech

The extraordinary story is only now emerging.

The cast of characters includes Adolf Hitler and his art dealer.

They amassed a collection of more than 1,000 paintings, drawings and prints by artists including Picasso, Monet, Matisse, Chagall, Otto Dix and Paul Klee.

The case made the headlines when some were found in a Munich flat belonging to an elderly recluse, Cornelius Gurlitt. Then even more showed up as officials probed further.

Now for the first time the tale is told in a new book by Catherine Hickley, with a wealth of details not previously reported.

DANTE is pleased to give an extract from this exceptional investigation. Watch for the concluding jaw-dropping question: Monet or Manet?

Catherine Hickey writes:

After the media revealed the existence of the Munich art hoard in Cornelius Gurlitt’s apartment in November 2013, Christoph Edel was appointed as his custodian to take care of the elderly heart patient’s complicated administrative affairs. Edel appointed Stephan Holzinger to deal with media enquiries and Hannes Hartung as the lawyer to handle claims for Nazi-looted works in the vast collection.

The action in February shifted to Carl Storch Strasse, a quiet street in an upmarket residential district of Salzburg, away from the bustle and jostle of the tourist-jammed arcades and cobbled alleys of the quaint old town centre. In the sedate suburb of Aigen, such luminaries as the famous German ex-footballer Franz Beckenbauer maintained homes.

It was here that Cornelius found the solitude he craved for many decades yet his health had prevented him from returning to his home in Salzburg for several years. His shabby, 1960s-built, two-storey detached house stood out in this manicured environment, alongside the grand villas with sophisticated security systems.

It was neglected, the kind of place children imagine is haunted, with its moss-covered roof, wild, overgrown garden, cracks in the walls and cobwebs over the front door. Its once-white walls were a grimy grey. Rusty latticed bars covered the windows, which were boarded up to shield the interior from prying eyes. Cornelius had even suspended a piece of wood from the ceiling in front of the letter box to thwart anyone who might have been tempted to peer through.

The residents of the street hadn’t seen its owner for months. Over the years, he had become the subject of much speculation and rumour. Some were growing vexed at the ‘spooky ruin in the middle of this nice area’, as Helmut Ludescher, Cornelius’s neighbour of fifty years, described the house. Local children were afraid to go and pick up their toys if they landed in his garden.16

The house harboured a secret. Not a corpse, as many of the neighbours suspected, but another astonishing cache of art including works by such masters as Monet, Renoir, Gauguin, Liebermann, Toulouse-Lautrec, Courbet, Cézanne, Munch and Manet. They were gathering mildew, dust and cobwebs. Cornelius had told Edel about his second trove, but insisted he would attend to it himself when he was feeling better.

A lithograph by Cornelia Gurlitt of a WWI hospital tent in Vilnius, Lithuania. Source: Kunsthaus Desiree/Knecht Verlag

Events forced faster action. Neighbours had complained to local authorities about structural damage to the house, particularly a large crack in the garage wall. The Salzburg construction authorities wrote to Cornelius demanding access to the entire premises on 17 February for inspection by a team including fire service officials and construction police.

This was the opportunity Edel needed to persuade Cornelius to let him move the paintings out of the abandoned house, where they were at risk from burglars. It was a task the elderly invalid was in no shape to deal with himself, either physically or mentally, nor had he been for many years, as Edel was to find out. Cornelius gave him permission to remove the artworks from the house but asked him not to take the rubbish out as he would deal with that himself when he was fitter.

On a misty, icy Monday in February 2014, Edel, Holzinger, Hartung and an art appraiser from an insurance company parked their cars a little way away and made their way to the house separately on foot, hoping to avoid drawing attention to their operation. After their arrival, two lorries with German number plates parked in the street. The full team included two art restorers and removal men.

They were unprepared for what awaited them. The first challenge was to open the front door. Mountains of rotting refuse in plastic bags barred the way. They pushed it open inch by inch, dislodging the rubbish little by little to create a wide enough space to enter. Once in the hallway, they found the strange contraption Cornelius had built to block the view through the letter box. He had fixed a post to the ceiling and using hooks and string, attached a large piece of plywood that dangled down in front of the door.

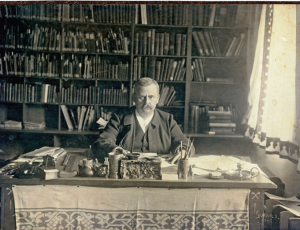

Cornelius Gurlitt senior, father of Hildebrand. Source: University archive of Technische Universität Dresden

Inside the house they were waist-deep in piles of decaying refuse overflowing from plastic carrier bags. The stench was overpowering. Bags of rubbish blocked the stairs and filled every room, interspersed with heaps of books and newspapers. Among the debris lay the precious masterpieces, some of them deliberately hidden. Wading through the trash was treacherous – it would have been so easy to inadvertently tread on a painting and cause damage worth millions. Locating the artworks scattered all over the house and separating them from the waste was going to be a delicate, risky, dirty and time-consuming business. The task was made even more complicated by Cornelius’s express wish that the rubbish should not be removed, only the artworks.

But the men knew that their window to work in peace was limited. Holzinger kept watch in front of the house, trying to keep warm in leather city shoes unsuited to temperatures just a little above zero. He realized it was only a matter of time before the media would cotton on to the activity in the abandoned home. As he was wearing a suit and tie and didn’t want to have to face reporters covered in filth, he could not in any case be of much help inside. A neighbour approached him offering to buy the house. He persuaded her to move on.

The first artwork the team discovered was hanging on a wall downstairs, a large-format Gustave Courbet oil portrait of an imposing bearded shepherd striding through a landscape holding a staff and a wide-brimmed hat. Others were harder to locate.

Cornelius had set some old wooden boxes on their sides to serve as bookshelves for his collection of cheap, yellow-jacketed paperback classics produced by the publisher Reclam. Edel spotted what looked like a pile of newspapers behind the improvised shelves. He delved into it and extricated an oil seascape: two sailing boats against a moody grey sky in an extravagant gilded frame. He looked at the signature and showed it to the insurance art appraiser.

‘Is this a Monet?’ Edel asked.

‘No,’ the appraiser replied. ‘It’s a Manet.’

Edel rummaged further to see what else might be lurking behind the bookshelf under the crumpled newspapers. He retrieved an Impressionist view of Waterloo Bridge that was lying on the floor. It may have been painted on a grey and misty London day but it was hard to tell, it was so dusty.

‘That’s a Monet,’ the appraiser said.

The Munich Art Hoard: Hitler’s Dealer and His Secret Legacy by Catherine Hickley is published by Thames & Hudson, £19.95 hardback

http://www.thamesandhudson.com/The_Munich_Art_Hoard/9780500252154