The Ortiz-Gurdián Foundation and its Contribution to the Cultural Development of Nicaragua and Central America

November 2, 2015

How I Escaped

November 14, 2015

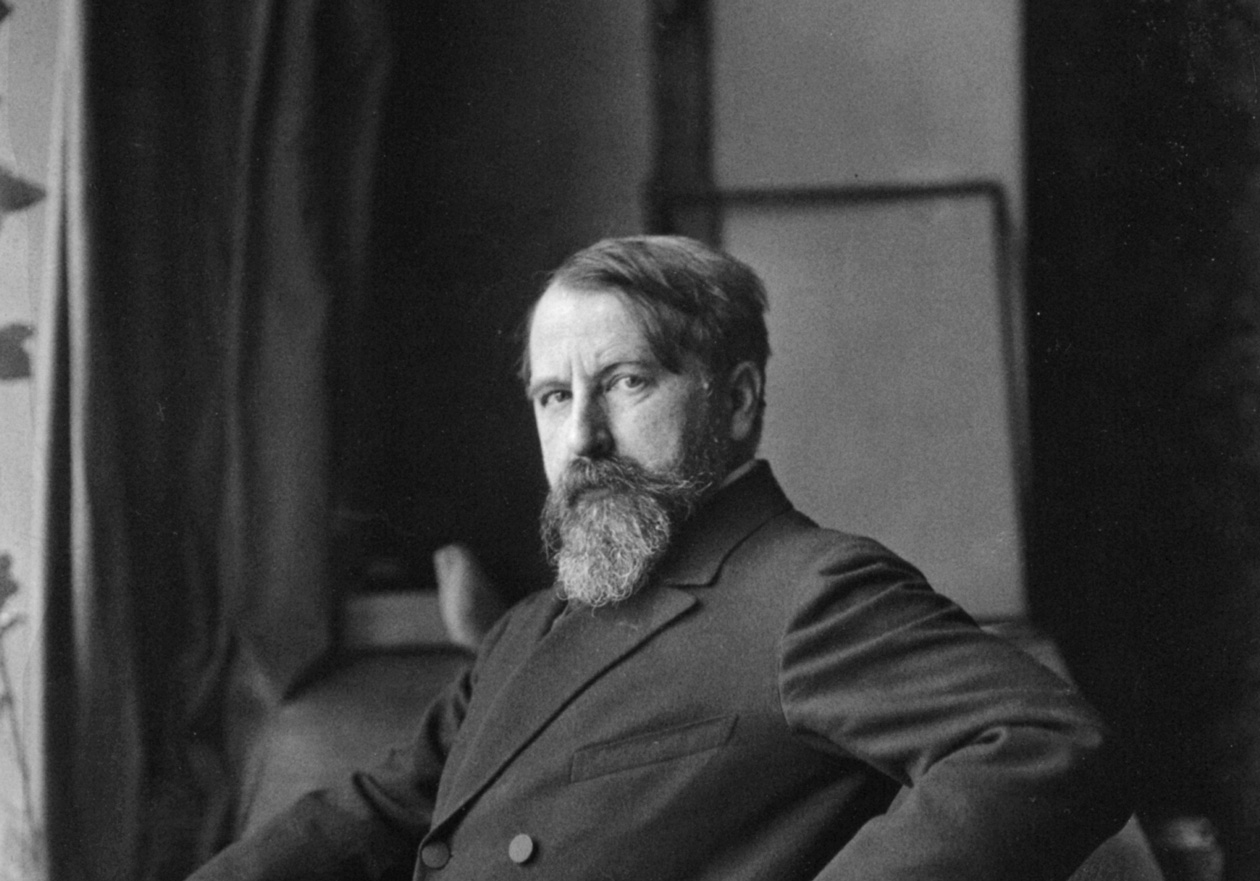

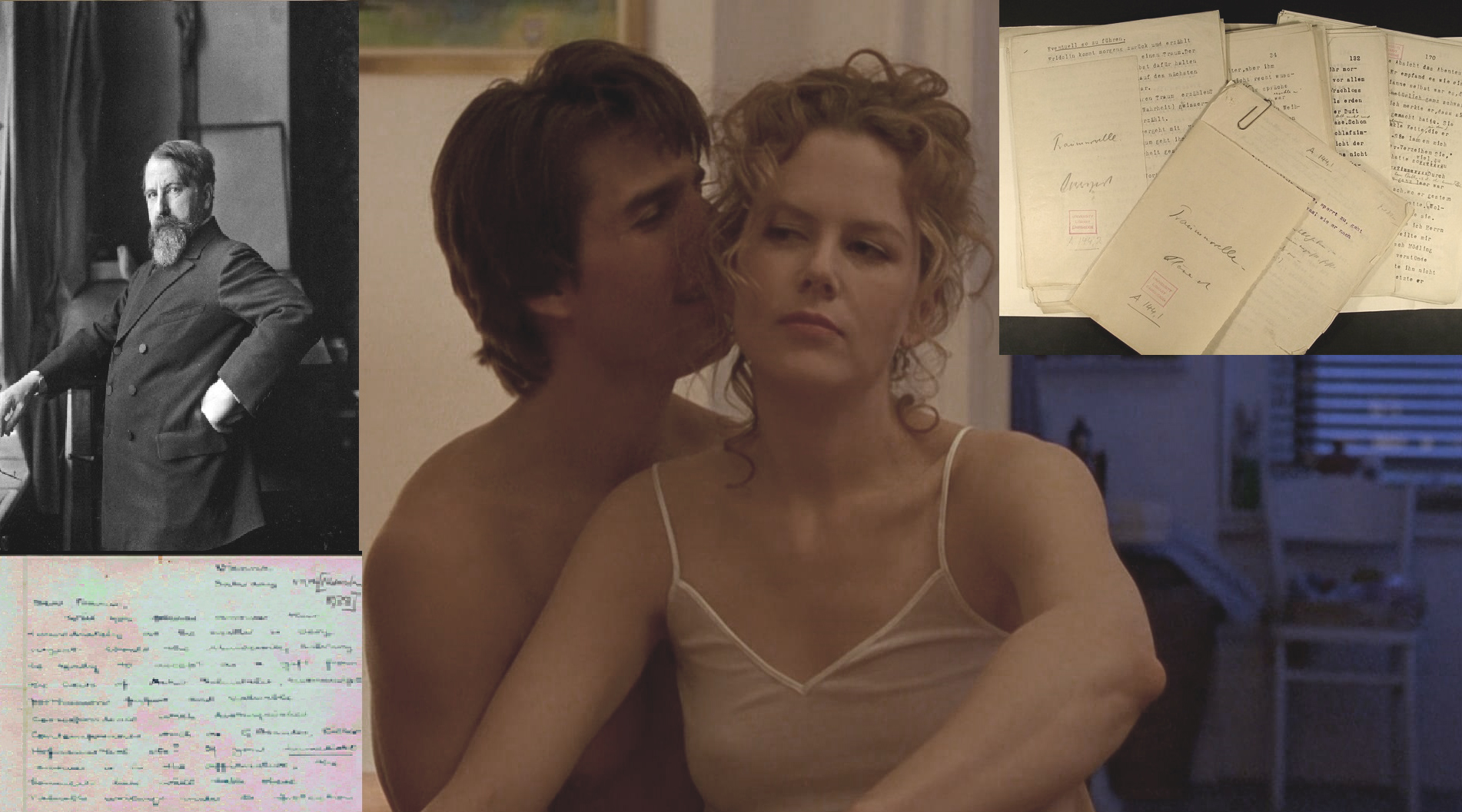

Author Arthur Schnitzler and manuscripts from his archive set against the film he inspired, “Eyes Wide Shut.”

Archive saved from Nazis by the man who inspired Kubrick – DANTE reports agreement

By Mark Beech

Saved from destruction by the Nazis and smuggled in secret to Cambridge U.K., the rescue of author Arthur Schnitzler’s archive is as dramatic as any fiction he committed to paper.

Now, more than 75 years after they were spirited out of Austria under the noses of Nazis intent on burning and destroying all Jewish cultural works forever, the author’s papers have a final confirmed resting place at long last.

These are the manuscripts of a man who was friends with Freud and corresponded with Gustav Mahler and Henrik Ibsen. A man whose writing, more often than not about sex or death, was later adapted for stage and screen by Sir Tom Stoppard and Stanley Kubrick – “Eyes Wide Shut” closely follows Schnitzler’s original story.

Now the archive has been officially signed over into the care of Cambridge University Library.

Personal note

It is odd how truth can be stranger than fiction.

This is probably because novelists and screen writers know that it is hard to suspend disbelief if events are too unbelievable.

True stories that are worth retelling – as in a lot of top news headlines – often are beyond amazing. That’s why they are compelling.

So with this story. Fact beyond the realms of fiction, truth almost twisted beyond reality.

*

I thought I’d seen it all on the Nazi-looted-art front, having previously edited dozens of Bloomberg News stories by Catherine Hickley, who is surely the world’s leading journalist on the subject. DANTE has already been lucky enough to extract a part of her impressive book “The Munich Art Hoard” here.

Cathy has since spoken at London’s V&A museum, pointing to the complexity of the situation.

Clearly, not every Jewish author or artist was able to get their work out of Germany and the countries it occupied in the way described below.

Many were sadly unable to save themselves, or their relatives, let alone their artworks.

The archives of countless artists were trashed in some of the most breath-taking cultural vandalism the world has ever seen.

Many other works were seized by the Nazis, with a dispute in some cases on whether works were handed over voluntarily or not. Jewish families were first forced to sell art for tiny sums, way beyond fair prices, and then had them confiscated altogether by the Nazis.

In such cases, statutes of limitations and restrictions on time for claims to be made mean that it is now often hard for rightful heirs to reclaim works.

After a decade, a buyer can simply say it was acquired in good faith, say from a reputable auction house.

This latest story about Nazis and art is very different, of course. It shows there is a solution with care.

This particular case was handled sensibly by all sides at all times and has a happy solution. If only this had occurred more often elsewhere, is all.

*

The tale of how Schnitzler’s archive came to Cambridge in the first place is a remarkable and complex one.

In a nutshell, the handover process began in the 1930s before being interrupted by the onset of the Second World War.

The latest announcement comes after several months of discussions with the writer’s grandsons and surviving heirs to his estate, Michael and Peter Schnitzler.

*

Arthur Schnitzler is not a name instantly known to many. His influence has proved to be greater.

From his birth in 1862, the son of two Jewish physicians, his course in life seemed mapped out. He duly qualified as a doctor in 1885. He was a restless, creative man and soon turned to writing instead. He married aspiring actress Olga Gussmann. They had a son, Heinrich. The couple formally divorced in 1921, though they continued to live together.

Schnitzler died on October 21 1931, in Vienna, of a brain haemorrhage, leaving an output that included a couple of novels, one of them acclaimed; many plays, which were both commercially and critically successful; considerably more short stories and novellas; as well as prolific nonfiction, mainly in draft form, such as letters and more than 8,000 pages of diaries.

Upon his death, his estate remained in his Vienna house with his ex-wife Olga, who was considered his widow by many, despite the formal separation.

Schnitzler’s works had already been denounced as “Jewish filth” by Adolf Hitler. There was particular fury about the 10-act 1897 play “Reigen,” each part of which shows how two different characters relate to each other before and after having sex: “the whore and the soldier,” “the actress and the Count” etc. It is sometimes called “La Ronde” or “Circle of Love,” as in Roger Vadim’s movie version from 1973. It was also turned into “The Blue Room,” by British playwright David Hare.

By 1933, all Schnitzler’s writing was banned by the Nazis in Austria and Germany. The works of Jewish artists were regularly being consigned to the flames of book-burning rallies across Germany. The Joseph Goebbels-organized conflagrations consumed classic works by Albert Einstein, Karl Marx, Franz Kafka and Freud.

It is lucky that many copies of these survived elsewhere. It is fortunate too that many unique works of art survived – while a few paintings were destroyed, they often had a useful monetary value and could raise cash for individuals or the war effort.

However, in March 1938, Germany invaded Austria and many prominent Jews were arrested and dispossessed. Schnitzler would have almost certainly been one of the first to have been detained if he was still alive and in Austria.

In the same year, following the Anschluss, Heinrich went to the United States to live.

Worried that the Nazis would very soon come for Schnitzler’s papers, Olga asked an acquaintance in Vienna, a student from Cambridge called Eric Blackall, if he might be able to help save them.

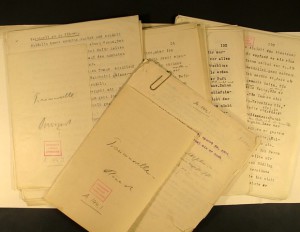

In March, at her request, Blackall sent an urgent message to his tutor Francis Bennett asking if Cambridge University Library would accept the more than 40,000 pages of Schnitzler’s literary archive. The library officials agreed immediately, and a diplomatic seal was placed on the material before Blackall organised its shipment from Nazi-occupied Austria. More than a dozen cases and cupboards of manuscripts, sketches, notes, correspondence and even Schnitzler’s death mask made their way across Europe to Cambridge.

A lot of his output was in the form of an extensively detailed diary, which the young student began at 17. (He had published a memoir of his youth during his lifetime.) The ailing writer only stopped the diary entries because of ill health just a couple of days before his death. Amid reflections on political news, family and literary life, there are graphic descriptions of his multiple affairs. His range of lovers had widened, including at least one of the actresses in his successful bedroom farces. As the funny fiction became serious reality, it’s hardly surprising that his marriage had broken up.

The communications about the archive between Blackall and England, also preserved in Cambridge University Library, have the character of a spy novel.

Blackall referred to the urgent need to see that “mother” (Olga) and “child” (the archive) were safely dispatched to England.

Once both were safe in Cambridge, a legal document was drawn up and agreed between Olga and the Library in 1939, giving the archive to the University.

However, Olga had neglected to notify the library that she was not Arthur’s legal heir according to his last will.

Heinrich was the sole heir. He asked for the archive to be returned to him and was told by the university librarian that the papers had been given by Olga and should remain there in safe keeping, pending discussions and clarifications.

Olga herself left for the United States, taking some of the most personal artefacts (such as diaries and family letters) with her. This was with the blessing of the librarian at the time.

Because of the outbreak of World War II, no further negotiations took place and Heinrich agreed to leave the archive in the custody of the library, provided that he was given access to the archive and that microfilm copies of the papers were made.

Heinrich’s son Michael – a well-known musician- was born in 1944 in California and he moved to Vienna with his parents in 1959.

Over the course of the following decades, the library maintained a correspondence with Heinrich, who worked on his father’s papers, but the Schnitzler family remained owner of the archive. The agreement between CUL and Schnitzler’s grandsons puts to an end a legally awkward situation, according to an e-mailed release.

Part of the archive, the draft of “Dream Story” (which became “Eyes Wide Shut”).

Courtesy of University of Cambridge

The archive includes a draft of his 1926 novella usually titled “Traumnovelle.” This is more widely known as “Rhapsody” or “Dream Story.” The book explores the author’s typical themes: a doctor protagonist (who may not be so far removed from his creator, or people he knew at least) and a wife having sexual fantasies about another man. It seems that romance, eroticism and sex are never far from his themes, if not obsessions.

The book was famously later adapted as “Eyes Wide Shut” by the American film director Kubrick.

As noted above, Stoppard has also taken inspiration from Schnitzler. He turned the 1911 drama “Das Weite Land” into “Undiscovered Country” in 1979. He later reworked “Flirtation,” from 1895, into “Dalliance,” some 90 years after it was written.

Schnitzler’s works were often controversial and even denounced by Adolf Hitler as examples of “Jewish filth.”

The Nazi stand is possibly also explained by Schnitzler’s unconventional and experimental writing style, which was later developed into the stream of consciousness method that was championed, very differently, by Virginia Woolf and James Joyce for example. If he had been Aryan, it is doubtful the German government would have cared. As it was, it was just another excuse to condemn him. (Now, decades on, his style is admired, much imitated, and the subject for doctoral theses.)

More directly, Schnitzler was condemned by the Nazis for taking a stand against anti-Semitism. He had Jewish protagonists such as Professor Bernhard (title character of a play) and Fräulein Else, from the novel “Der Weg Ins Freie.”

The archive in Cambridge also contains Schnitzler’s only surviving letter to his friend and admirer Sigmund Freud. The writer’s sexual confessions were an important component in their relationship. Freud said he could learn a lot more quickly from a short story by the author than he could in hours of psychotherapy with patients.

The archive also has Schnitzler’s correspondence with Theodor Herzl, the founder of Zionism, and other leading artists and writers of the era – such as Ibsen, Richard Strauss and Mahler.

Cambridge University Librarian Anne Jarvis said the library “has always been proud of the role it played in saving the Schnitzler archive from certain destruction.”

His “unique legacy continues to resonate and inspire, just as it has over the last 75 years,” she said. “We are committed to making this fascinating archive available to as many people as possible.”

The archive is currently being opened up to scholars and other interested readers by major edition projects in Austria, Germany and the U.K. This will result in digital editions of works from 1905–1931, to be hosted, with open access, by the University Library.

Andrew Webber, Professor of Modern German and Comparative Culture at the university’s Department of German and Dutch, leads the U.K. editorial team, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

“The edition projects are already making remarkable discoveries as the teams of scholars decipher and analyse drafts and notes recorded in Schnitzler’s idiosyncratic handwriting,” said Professor Webber. “They promise an exciting new view of the works and the creative processes of this key figure.”

The archive sits in the library among more than eight million books and periodicals, one million maps and many thousands of other manuscripts by Isaac Newton and Charles Darwin. It also has a copy of the Gutenberg Bible from 1455, the earliest European example of a book produced using moveable type.

Dante is hugely indebted to Cambridge University Research Communications for providing much of the research material used in this article.