Dante Recommends: Naked Calendar in Aid of Charity

November 21, 2015

COP21 | United Nations Paris conference on climate change

November 30, 2015How non-digital writing is freeing creativity

By Mark Beech

The typewriter: a museum piece or a machine of the future?

It is not as silly a question as it may sound.

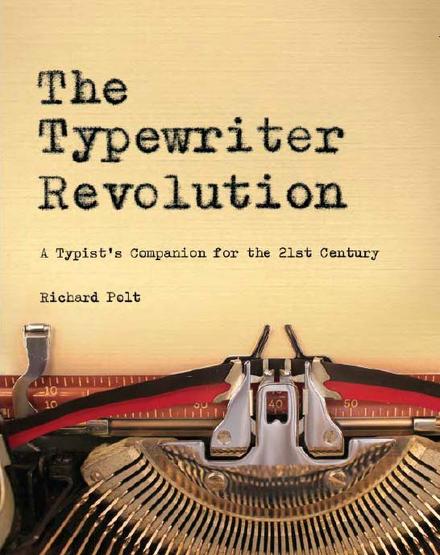

An impressive new book, “The Typewriter Revolution,” looks at its history and tries to make sense of it.

I was sent a review copy of this impressive, lavishly illustrated work. Richard Polt, the author, discusses how to choose and care for a typewriter.

What follows is review mixed with some personal reflections on our relationship with the typewriter.

*

What do Tom Wolfe, John Mayer, Danielle Steel and Tom Hanks all have in common?

Like thousands of other poets and artists, Polt says, they are fans of the typewriter and its renaissance in the 21st century.

He also provides insights on how to get involved in the typosphere, and why quality and physical process are more important than speed. As digital devices become ever more pervasive and powerful, people will need distance from them, and typewriters are a liberating way to take a break from the digital environment, he argues.

Polt, a professor at Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio, has for more than two decades pursued his love of the typewriter as a collector, creator of “The Classic Typewriter Page” editor of the magazine “ETCetera,” repairman, and frequent typist.

*

Recently I was interviewing bookbinder Mark Cockram for an interview to appear in a future edition of Dante.

Now that was already surreal enough, talking about the future of books at a time when the death of the printed word has been much reported.

So too has the imminent decline and fall of all written media.

In the course of that conversation with Mark Cockram, and there will be much more of this in online and future print editions – oh yes, Dante proudly goes onto glossy paper and to hang with the consequences – he mentioned in passing on how a student of his wanted to create a custom label for the binding of a book she was preparing.

I was imaging he was about to say that he had an old Dymo machine somewhere. Instead, he said that he proudly got down from the shelf an old portable typewriter.

She was amazed: “What’s that?” she asked.

(It’s a typewriter.)

“Wow, where can I buy one?”

(Probably from any car boot or junk sale for virtually nothing.)

The story was revealing.

*

There comes a stage when our past catches up with us and bites us as we look to the future.

It’s like the punchline at the end of the old “Monty Python” sketch about the “Four Yorkshiremen.” After some minutes of endless one-upmanship stories on how awful their lives were, getting more and more preposterous and impossible, they say “and you try telling the young people of today that.” “They won’t believe you.” “They won’t.”

So I grew up at a time when telephones weren’t so common, still less mobile phones; when much communication was done by paper letters, usually handwritten – or typewritten. Delivered by snail mail, none of your instant email stuff. Hands up if you remember that.

*

A typewriter is not a bad computer, just as book is not a bad website.

There are wonderful insights in Polt’s book. I like the quotes from Hanks, who particularly comments on the noise of the keys. We probably all have enjoyed pressing them hard for maximum noise, especially if angry, or fast – or lightly when in a hurry. Therapeutic bashing of computer keyboards isn’t quite the same. Hanks says when you get a good rhythm going, “the muscles in your hands control the volume and cadence of the aural assault so that the room echoes with the staccato beat of your synapses.” This is followed by an amusing insight. Hanks’s favourite typewriter is a 1940 Corona Silent. You couldn’t make it up.

*

You could not save a template for even a common document: one usually had to physically do it again and again. Mistakes were corrected by using hard typewriter erasers or Tippex paper, Snopake or whatever.

If you remember this era, good – me, I recall my first typewriters, a toy Mattel with a false keyboard and rotating central wheel, then a barely-working Petite.

My mother started learning – touch typing and/or shorthand was expected for a secretary and she was thinking of returning to the world of work.

When she later had a change of heart, she gave me her portable, metal Olivetti Lettera 32 – my first proper typewriter and a moment of the truest joy. My old toy machines I ceremonially chucked out of an upstairs window onto our paved patio. I then gleefully bashed them to bits with a hammer. My parents were quite shocked by this behaviour. Their Mark, such a nice respectable kid, was smashing up his toys. But now I had a real typewriter, a life changing status. It had a sculptural blueish top and a black flat base. This was not a toy any more, this was the real thing. It made a wonderful clackety clack sound. I wanted to write so bad and this was the best present, ever. I immediately started typing out my first attempts at novels, spending hours a day. I was about ten or 11 years of age.

When I made mistakes I sometimes overtyped them with a row of xxxs or kept the error and changed the sentence to avoid the fiddly effort of erasing the words. Soon I was wearing out typewriter ribbons, occasionally typing only in red so I could use up that part of the ink.

The Lettera had Pica 10 type and did not have a 1 numerical key so I had to press the lower-case letter l as the closest I could get. Years later I got a similar Lettera but with a different keyboard and Elite 12 type.

I still see the legacy now. I was transcribing what came to be one of my first published poems, “Cats,” and meant to type “gleaming green.” My finger slipped and started “gr” so I changed the wording to “growling and gleaming green” and that’s how it appeared in my first book, “Passionfruit.” Most domestic cats in my experience rarely gutturally growl as such, even when provoked or pleased, but there we are. (One review said I was “a promising young poet.” Nobody mentioned that cats don’t growl – purrs or meows are more normal.)

*

Polt’s book points out the Lettera 32 came with a tabulator – something not so common on cheaper machines, which would often set tab points every ten characters, whether you liked it or not. The portable usually comes in its own blue zippered case with a black flash on it. Polt says Lettera 32 users include Leonard Cohen and Sylvia Path, but others who followed had their own happier thoughts on it too. The Lettera, designed by Ettore Sottass, is now often overshadowed by another of his 1960s creations for Olivetti, the Valentine, with its wonderful detached front and outrageous colours such as Ferrari/ lipstick red.

*

My university thesis had to be typed up and I used a professional typist in my home town, who did the job at some expense. (It wasn’t easy because the footnotes needed to be at the bottom of each A4 page they related to, so she needed to retype some pages multiple times to get it right.)

I became a reporter and at my first newspaper a couple of years later, I had a thunderous Royal typewriter on my desk. It was some 40 or 50 years old. Every single page had to be carbon copied, then was sub-edited by hand and laboriously retyped by the printer. Computers had yet to exist. The Internet was unknown.

The clattering of typewriters in a big newsroom such as the Birmingham daily paper I worked on was an amazing din: maybe a fast news guy machine-gunning the front page lead story furiously, while the woman’s editor was slower and more methodical, with the daintiest finger-hunting tap, tap, tap.

*

Polt quotes Gay Talese: “Three hundred reporters could be seen at a single glance making clattering sounds with their fingertips on the metal keyboards of their bell-ringing typewriters, their facial expressions alternating between frustration and satisfaction, all within view of everyone else, and all calling aloud to copyboys whenever they wanted their completed stories to be rushed to an editor.”

*

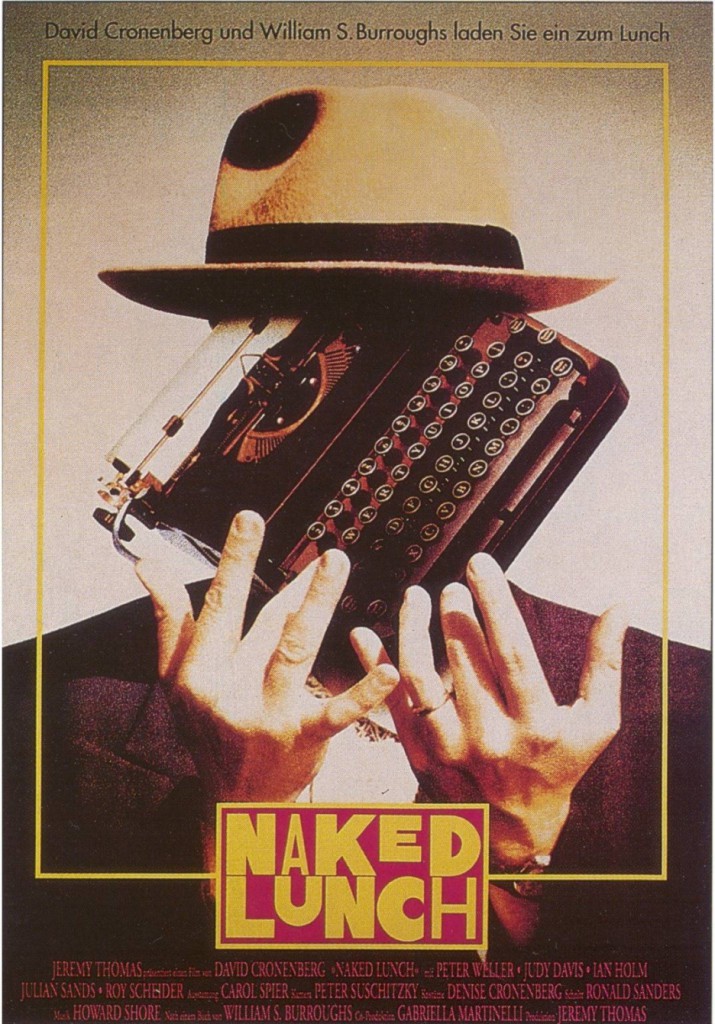

I interviewed a local silversmith, Duncan James, who collected typewriters. In his home, then in Brackley, Northamptonshire, he had a workroom with dozens of machines all over the floor like menacing black beetles or cockroaches in echoes of “Naked Lunch.”

Duncan had some with usual keyboards, strange shift platens and others that didn’t look like typewriters at all but odd metal butterflies – now there’s a name for a band, Iron Butterfly. (What, you mean it’s been done?) Or one like iron maiden torture machines. (Ok, so that’s been done too).

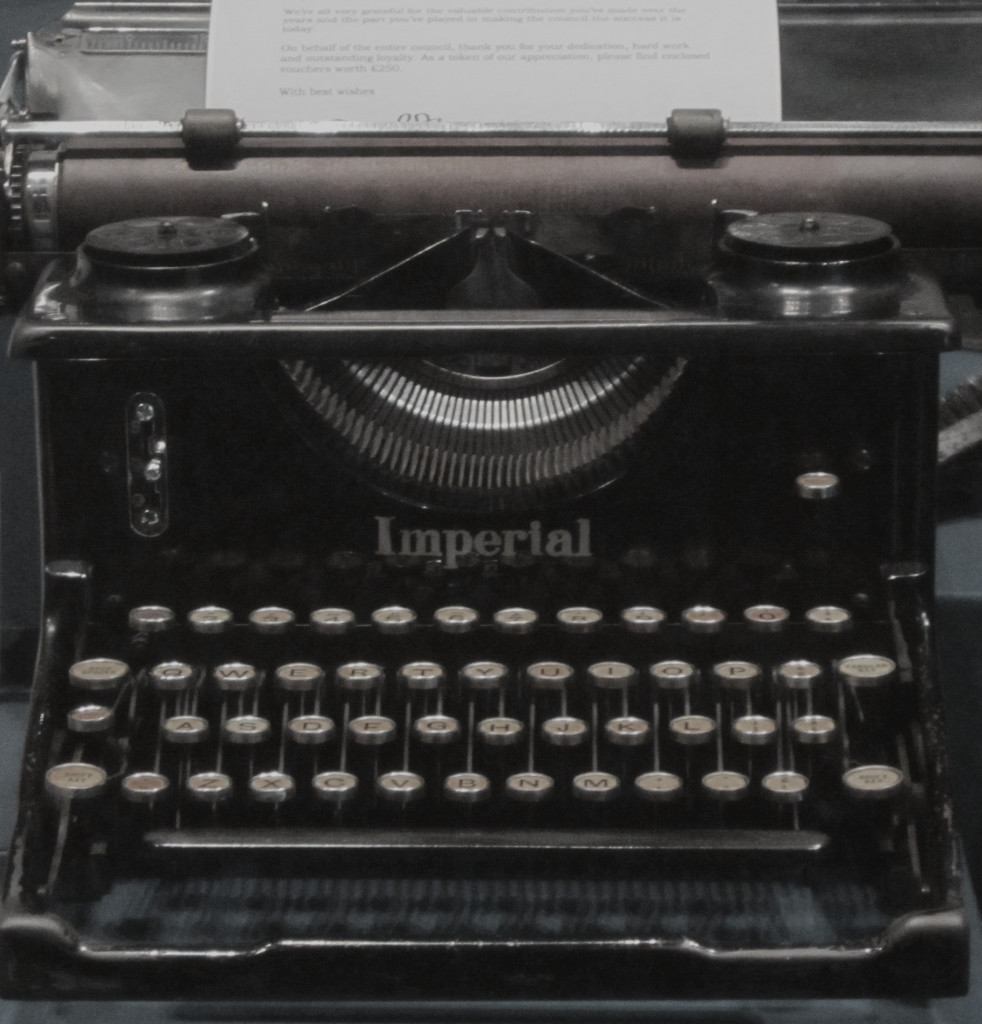

Soon I bought my own vintage Imperial, and then ancient Royal which had been fully restored, even with a re-rubberised print roller and polished like a Rolls-Royce. I had an electric Silver Reed, and was thinking of going for a golfball and then Amstrad introduced the PCW and I was onto computer and hardly looked back, except with nostalgia maybe.

*

The Imperial is a British machine, says Polt, with an interesting feature of an exchangeable keyboard and type basket – they literally will come right out of the frame. The glass sides on some of them are especially classy.

*

Every typewriter reference has fascinated me ever since – “The Paris Review” interviews with authors on their working methods; volumes with titles such as “Homage to Qwert Yuiop” (Anthony Burgess’s essays were published in the United States as “But Do Blondes Prefer Gentlemen?”); William Burroughs’s surreal typewriters, as mentioned, in “Naked Lunch”; the typewriter scene in Stephen King’s “Misery” – these things do weigh a ton; memoirs such as “Burying the Typewriter” by Carmen Bugan, about samizdat in Ceausescu’s Romania..

Duncan James moved west with his silver business and I lost touch with him. I thought of him though when I bought manuals on the subject: “Antique Typewriters: From Creed to Qwerty” by Michael H. Adler and “Antique Typewriters and Office Collectibles: Identification & Value Guide” by Darryl Rehr.

*

Polt points out one can self-publish from a typewriter with no digital record – steampunks, activists and more all love their manual typewriters because they don’t run out of batteries, don’t need electricity – and basically set them free from surveillance.

Polt’s book is a fine summary of the typewriter. A fine celebration. One hopes it is not a fine memorial too but the start of the next stage.

*

When I tweeted about the Polt book recently, there were responses from the likes to @typewriterRev himself and other collectors, some showing photos of their pride and joys. There clearly is a lot of interest of there.

Thanks to the standard keyboard I will be paying homage to QWERTYUIOP for the rest of my days, as we all will be. I am now all digital, for writing as well as photography, but I miss the past.

As time goes on, I think I even miss the reloading of paper, the fiddling with inky ribbons, the cleaning of keys (Blu-Tack was a good way of removing excess ink clogging the hoes of the “O”s), the bell going “ping” at the end of each line and hitting the return key or shoving the carriage return. That’s what we used to do.

“And you try telling the young people of today that.” “They won’t believe you.” They won’t.

*

“The Typewriter Revolution: A Typist’s Companion for the 21st Century” by Richard Polt (November 2015) is published by Countryman, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, at about $22.95 (256 pages)

Information: http://www.typewriterrevolution.com/

Afterword: I wrote this article in November 2015. Some months later I was editing a Lisa Contag piece for ArtInfo which mentioned the Ettore Sottsas design of the Olivetti Valentine like the one pictured above, with its quirky detached red piece in front of the keyboard.

The best part of a year later, I was at the Design Museum, London. I was reviewing its re-opening in the former Commonwealth Insititute. Looking around, I saw an Olivetti Valentine on display. As I remarked on it, a American guy said to me: “bet ya don’t know what that is – it’s a typewriter!” (The exact same irony as when I was at The Beatles Museum in Liverpool and an American-sounding tourist said “you must be too young to know anything about the Beatles” – erm, I only have every record, grew up listening to them, at one stage living in Liverpool and I have since interviewed three of the band.) In response to the typewriter question, “Yes,” I said, “I do actually know that, thank you. Typewriters are amazing.” I almost said: “I have a number myself, I grew up listening to them and have written thousands of articles on them.” Like this one. But life is too short. End of story.