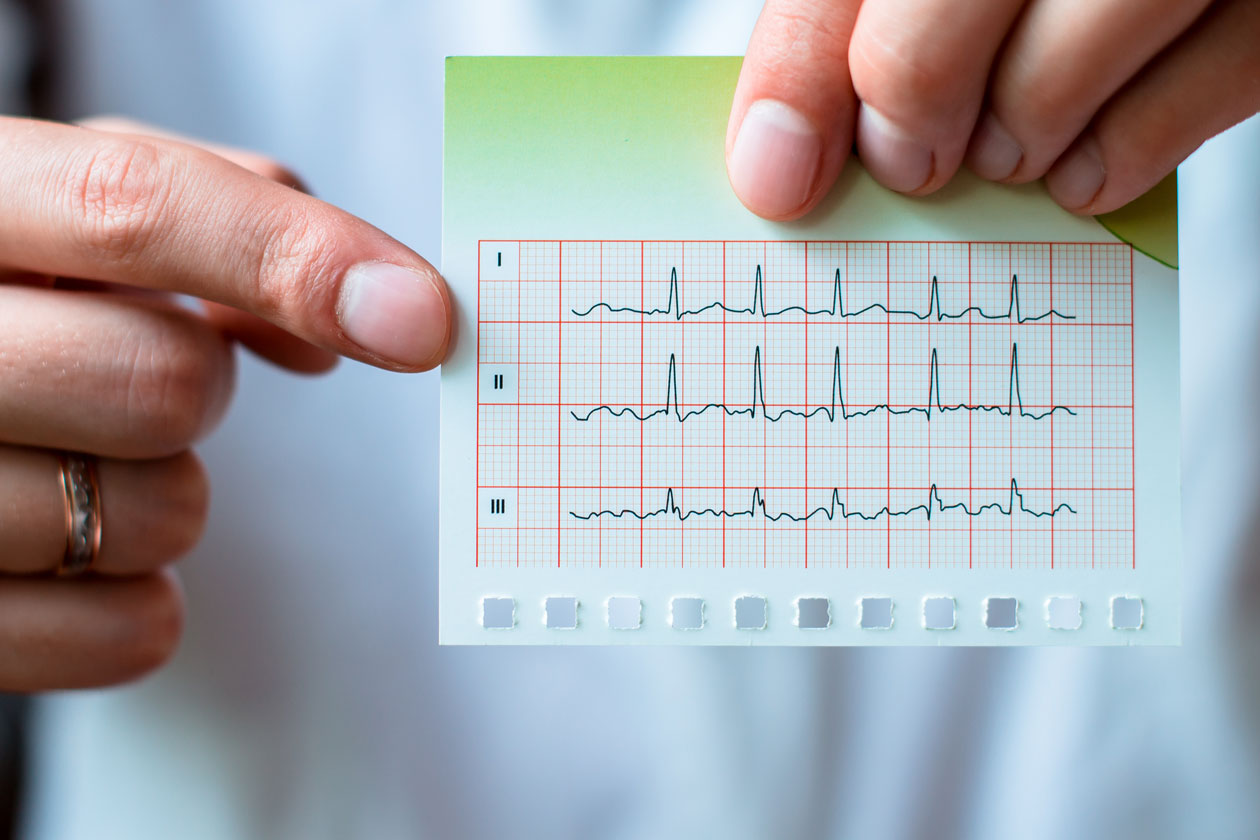

Medicine’s quiet revolution: Dante reports. Live-saving news for heart patients.

December 11, 2015

Goodwill to all? DANTE recommends a play that speaks volumes about life’s evils – and how to avoid them

December 26, 2015In our continuing exploration of how various religions and belief systems incorporate the concept of an angel, Dawn Collins enlightens us with how these go-betweens between man and higher spiritual being manifest themselves in the Buddhist tradition.

by Dawn Collins

In recent weeks Dantemag has reflected upon the theme of angels and angelic visions in monotheistic theological traditions. This week we explore possible parallel beings in Buddhist traditions and their significance on a spiritual path. If in Christian thought, angels can broadly be defined as created beings without bodies, then in Buddhist traditions a wide range of local deities and spirits might fit the bill. However, as has been pointed out in previous editions of Dantemag, although angels are not necessarily forces of good, as in the case of Lucifer, the most renowned of the fallen angels, the term, as used in common speech, generally brings to mind holy beings and messengers of God, such as Gabriel. Such beings appear in dreams and visions to foretell of great occurrences, such as the birth of Christ, or to forewarn of danger; they are both mediums for the divine and protectors for those whose purposes are divinely blessed. This type of angel in monotheistic traditions brings to mind the Buddhist idea of a Bodhisattva; a truly great and compassionate being who has evolved far on the path to becoming fully enlightened, the full Buddhahood which represents the pinnacle of the Buddhist path, and whose defining feature is that of compassion. The word Bodhisattva means just that: a being on the path to enlightenment. These beings, although not strictly speaking ‘created’ in the sense of having been formed from light or some such effervescent matter by a creator god, are, nonetheless, comprised of something far more subtle than the mud and clay of us ordinary mortals.

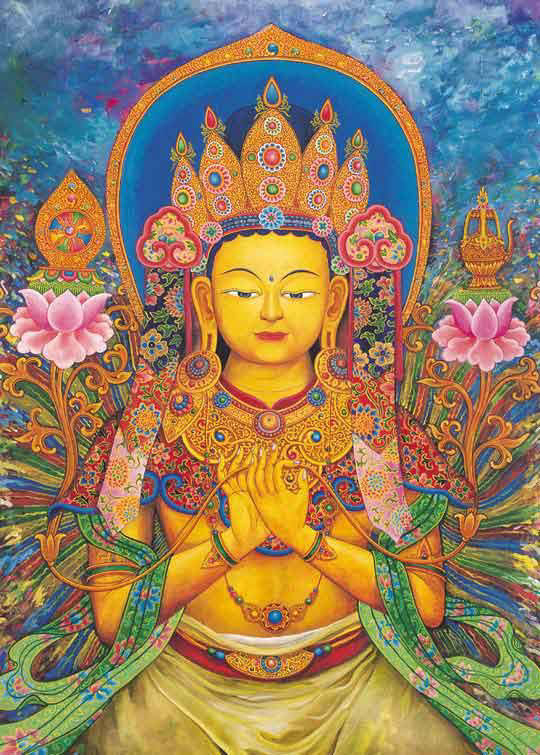

In the later thought of Mahāyāna Buddhism, founded on the work of the philosopher Nāgārjuna who lived around the second and third centuries BC, Bodhisattva figures abound. Their path to enlightenment entails a singular commitment to attain this highest of realisations in order to release all beings from the sufferings of our ordinary existence. In short, their raison d’être is a notion of great compassion, a love for others which surpasses any usual understandings of altruism. Buddhist histories are threaded through with story tellers of the rarest quality and their numerous anecdotes illustrate the transcendent compassion of the bodhisattvas – holy, one could even say angelic, beings. In the Indo-Tibetan tradition, perhaps the best known and most worshipped, in the sense of aspired to, is the Bodhisattva known as Avalokiteśvara, who has a thousand arms.

This Bodhisattva, known as Chenrezig in Tibetan, has a thousand arms with an eye in each palm of their hand so as better to discern where all the suffering beings in the world are to be found and thereby offer help. The definition of help here is in an ultimate, eschatological sense, help born out of profound compassion so, although it will be of practical assistance in addressing their immediate needs, it goes way beyond this as its ultimate aim is to link up with them, creating a relationship leading to the highest awareness and consequently completely releasing them from all suffering.

The Dalai Lamas of Tibet, a line of Tibetan rulers before the 1950s, are considered by Tibetan Buddhists as a series of reincarnations of the same being: the bodhisattva Chenrezig. As such, the Dalai Lamas are considered to offer both spiritual guidance and protection to the peoples of Tibet and indeed those of our world. Bodhisattvas such as Chenrezig can somehow manifest matter out of their subtle bodies, appearing to mere mortals in forms they can comprehend and engage with. This highlights a most remarkable feature of such Buddhist thought if applied to everyday life. Logically speaking, if such Bodhisattvas as extremely elevated and holy beings can manifest themselves in worldly forms for the benefit of mankind, quite simply, any being, human or animal, we meet could be one. This is perhaps best explained by way of one of those Buddhist story tellers’ anecdotes: the story of Asaṅga and the Bodhisattva Maitreya.

Asaṅga was a fourth century Indian pundit who became one of the founder members and major exponents of the Buddhist Mahāyāna yogācāra school of philosophical thought. He was also a great meditator. In fact, he spent no less than twelve years in a cave attempting to ‘realise’ – by which is broadly meant, to embody the qualities of – the bodhisattva Maitreya.

The Bodhisattva Maitreya epitomises the altruistic Bodhisattva ideal in the sense that the name itself means ‘loving kindness’. According to a prophecy found in the earliest of Buddhist textual sources, the Pāli Canon (Cakkavatisihanada sutta, Digha Nikaya 26), in a time when the world is in an exceptionally dark place, the Maitreya will come to realise full Buddhahood and regenerate Buddhist thought at that time by teaching the populace how to put it into practice.

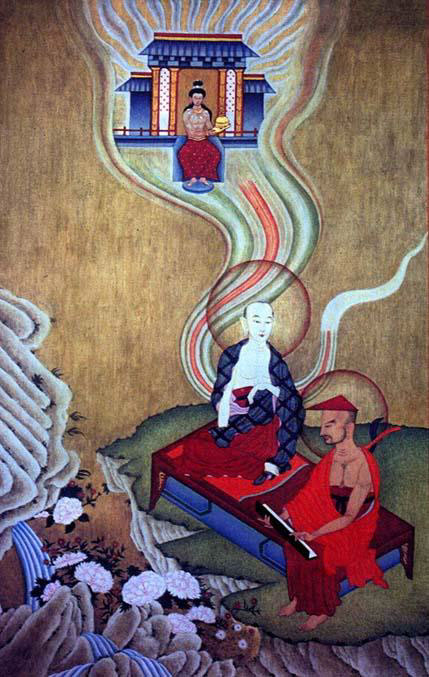

The story goes (Sogyal Rinpoche, The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying; Geshe Lhundub Sopa with David Patt, Steps on the Path to Enlightenment; Victoria Huckenpahler (ed.), The Great Kagyu Masters: The Golden Lineage) that during the twelve years he spent meditating in a cave, Asaṅga hoped to receive a dream or vision of Maitreya, to reassure him of the worth and progress of his spiritual practice. The aim of such meditational practice, as has been intimated, is to embody the qualities of the deity concerned, to become that holy being, in some sense. Signs of success in this goal are generally held to be dreams and visions. In this case, Asaṅga had neither and, every three years or so into his twelve year retreat, he almost gave up and abandoned his cave. But something always took him back there. Finally, after twelve years, without having had any dreams or visions or received any sign from the Bodhisattva Maitreya, Asaṅga left his cave desperately dejected. On the path from the cave he came across an injured dog. The dog’s hindquarters were in a state of complete decay and riddled with maggots. Asaṅga’s heart broke with compassion. He resolved to clean the dog’s wounds and do what he could for the poor animal. He cut off a piece of his own thigh to give to the dog as food,in some versions of the story; in others he did this to offer to the maggots so they would not starve once he had removed them from the dog’s body. When it came to removing the maggots, Asaṅga realised that using his fingers risked squashing the maggots’ delicate bodies. So he decided to use his tongue. As his tongue reached into the decaying flesh of the wounded dog out of immense compassion for both dog and maggots that they both dissolved and Asaṅga finally saw his vision of Maitreya.

When Asaṅga asked Maitreya why the Bodhisattva had not appeared to him in all those twelve years of meditation retreat and devoted practice, the Bodhisattva answered he had never left Asaṅga’s side throughout all that time. The moral of this tale is of course that the highest in us all, holy beings and the best of altruistic intentions, lie within us and are ever at our side, if only we have eyes to see. Once the dross of the selfish mind and its illusions have been swept away by the transformative power of meditation mingled with the power of love, the power to see what has always been there occurs naturally, like, as a common Buddhist analogy goes, a lotus appearing from the mud. In Asaṅga’s case it was only when the most profound of altruistic loves was born within his heart/mind that the angelic vision of the compassionate Bodhisattva who he had been aspiring to could be finally perceived.

Dawn Collins is a founder member of natural movement

http://www.naturalmovement.org.uk and belongs to the Body Health and Religion Research Group http://www.bodyhealthreligion.org.uk/BAHAR/index.html. A professional dancer by training, Dawn also practises as a Traditional Thai Massage and a Shiatsu therapist. She approaches bodies through the light of the intimate connection between healing and dance, theatre and artistic expression. Her experience has also been applied to academic work, researching on spirit concepts and healing in Tibetan traditions. Recent publications include a chapter on Tibetan ritual dance in ‘Dancing the Gods’ in Monastic and Lay Traditions in North-Eastern Tibet, published by Brill’s Tibetan Studies Library.