Near-Death Experience – to One to Watch

March 11, 2016

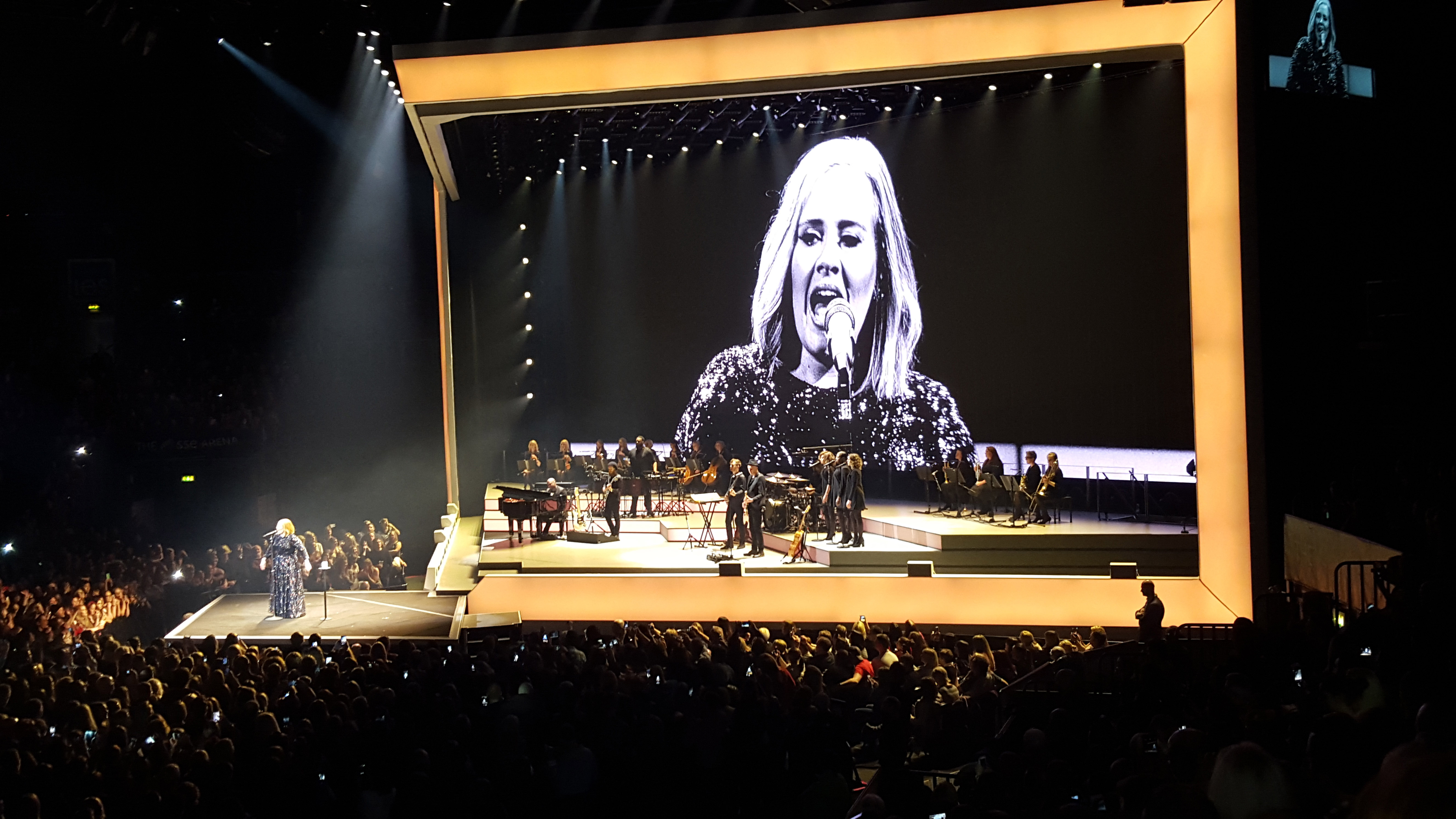

Adele: The Next Stage

March 28, 2016In this day and age we are overwhelmed by giant internationals who flood the market with their uniform products, but when global commercialisation is banished and the industry returns to its roots, then individual artistry and alchemy produce magical delicacies. Chocolate aficionado Marc Forget discovers one such magician in a hamlet in France.

By Marc Forget

At first glance it is hard to imagine a link between the cocoa-producing jungles of Ecuador and this old farmhouse in the hamlet of Charbonnière, on a hillside above Seyssel in France’s Rhône-Alpes region. About 50 km southwest of Geneva, Seyssel is much better known for its artists’ community than for its chocolate. However, in a little workshop behind her house, Clarisse Poudenx creates magic from local ingredients mixed with the ‘food of the gods’ she mostly sources from Ecuador. When people in the region crave good quality hand-made chocolates they come to La Chocolaterie du Hameau in Charbonnière, where for the past seven years Clarisse has been creating unique treats such as dark chocolate with roasted and caramelised fennel seeds, rich ganache perfectly balanced by the slight bitterness of walnut pieces, or little sticks of apple and pear paste covered in dark chocolate.

For most of Seyssel’s history (it goes back to Roman times), chocolate was unknown in Europe. Until the 16th century theobroma, the ‘food of the gods’, only grew in southern Mexico, Central America, and the northern Andean region of South America. The earliest evidence of cultivation and use of cocoa was found in Honduras, dating back to 1,400 BC. Prior to contact with Europeans, cocoa was mostly made into an unsweetened drink enjoyed hot by the Mayas while the Aztecs preferred it cold. It didn’t take long for Europeans to begin enjoying the exotic new flavour; cocoa was first taken to Europe in 1585, and the first chocolate house opened in London in 1657, starting a craze that offered an alternative to the coffee houses or ‘penny universities’, which were very popular at the time. Europeans soon began adding sugar and spices such as cinnamon to the hot drink.

For most of Seyssel’s history (it goes back to Roman times), chocolate was unknown in Europe. Until the 16th century theobroma, the ‘food of the gods’, only grew in southern Mexico, Central America, and the northern Andean region of South America. The earliest evidence of cultivation and use of cocoa was found in Honduras, dating back to 1,400 BC. Prior to contact with Europeans, cocoa was mostly made into an unsweetened drink enjoyed hot by the Mayas while the Aztecs preferred it cold. It didn’t take long for Europeans to begin enjoying the exotic new flavour; cocoa was first taken to Europe in 1585, and the first chocolate house opened in London in 1657, starting a craze that offered an alternative to the coffee houses or ‘penny universities’, which were very popular at the time. Europeans soon began adding sugar and spices such as cinnamon to the hot drink.

The most common form of chocolate today, the sweet, solid treat we so commonly enjoy, wasn’t developed until the end of the 18th century in Italy. Chocolate can be made with only three main ingredients: cocoa powder, cocoa butter, and sugar. An emulsifier is normally used (most often soy lecithin), and many producers add vanilla, which also originally came to us from Mexico and Central America. Milk chocolate, which in addition to the above ingredients contains milk and cream, is the best-selling type of chocolate, whereas white chocolate, which contains no cocoa powder (only cocoa butter, sugar, milk/cream and vanilla), sells the least.

Chocolate is big business, with worldwide consumption at over 7 million metric tonnes annually. Per capita consumption varies widely; in 2011 the UK was at the top of the list with 11kg per person, while Germans ate 7.5kg, Canadians consumed 3.5kg, and Mexicans, living in the region where cocoa was first cultivated and consumed, only enjoyed 0.7kg each on average. In the US chocolate outsells all other non-chocolate candy by a factor of nearly 2-1, and in 2013 chocolate sales topped $20 billion. Worldwide they exceed $50 billion.

At her small workshop near Seyssel, Clarisse Poudenx doesn’t aim for industrial scale production. One of her pleasures is getting up in the middle of the night and going into her workshop to enjoy the smell of the chocolate that’s slowly being melted to provide the foundation for the delights she’ll be creating in the morning. While much of the chocolate Clarisse uses comes from Ecuador, she has also been using a Tanzanian product with a different taste and texture profile. Careful selection of bulk chocolate is paramount in the world of speciality products, especially for small boutique operations like La Chocolaterie du Hameau for whom it is not economical to select, ferment, dry and roast the cocoa seeds, then grind and heat the nibs to make the chocolate liquor that gets combined with sugar and other ingredients. Although pleased with the chocolate she is currently using, made from Ecuadoran or Tanzanian cocoa, Clarisse continues to sample new products, and during my visit to her workshop she had me taste a new chocolate from Vietnam. I found it delicious with intense flavours that linger and a very pleasing creamy texture. The next step will be to purchase a small quantity to see how she likes working with it, and how the product tastes after being heated, worked and cooled. To show the effect of this processing on the chocolate, Clarisse had me taste the Ecuadoran product she uses (slightly sweeter and milder than the Vietnamese) before it has been melted, ‘worked’, and cooled, and after it has been processed. Even though there were no ingredients added, the processed product had a slightly different flavour and texture—and the effects of processing will vary depending on the temperatures, times and techniques used, something I would not have guessed.

According to Clarisse, one enters the world of chocolate-making the way one commits to a religious life – it is a vocation and a passion. Her first career was nursing and she considers her current occupation a continuation of her life-long commitment to helping people heal, be healthy and feel good.

Seyssel – by Nathalie Lambert

The health benefits of consuming moderate amounts of dark chocolate have been expounded in numerous studies in recent years. A 2011 Cambridge University study involving 100,000 participants showed that eating chocolate twice a week could reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and stroke very significantly. Consuming chocolate regularly has also been linked to lower blood pressure and reduced levels of LDL cholesterol (the bad cholesterol). According to the Harvard School of Public Health, regular consumption of chocolate has been linked to longer life. Perhaps the most beneficial effect of chocolate is on our mood; the leader of the Cambridge study stated that chocolate may well improve people’s quality of life because it has been proven that eating chocolate releases endorphins in the brain. It just makes us feel good!

Although most of us feel happy when we eat chocolate, some do express legitimate concerns about the environmental and social impacts of the cocoa industry. The cocoa-producing tree only grows within 20 degrees of the equator, and is exclusively cultivated in poor countries, while the countries that process and consume the bulk of the world’s production are among the richest and lie far from the equatorial zones. Less than 0.5% of the total production is produced organically, and only about 0.1% is sold with the Fair Trade label on. Even though cocoa originated in the Americas, the region now only produces 15% of the world’s total, while 17% comes from Asia, and Africa harvests the lion’s share, at 68%. Côte d’Ivoire alone supplies 33% of the world’s production. Along with deforestation and pesticide use, child labour and other exploitative employment practices are serious concerns some groups have been raising with the industry. Part of the difficulty in bringing about quick changes is that between 80 and 90% of annual cocoa production comes from 6 million small, family-run farms in countries as diverse as, Ghana, Papua New Guinea and Brazil. At the other end, 80% of the world’s finished chocolate is sold by only six multinational companies. Among global agricultural crops, however, cocoa is quite insignificant. With a current annual production of only about 5 million metric tons (MT), it is dwarfed by rice at over 738 million MT, and sugar at almost 1.85 billion MT. The environmental and social issues affecting cocoa are also a factor in the production of these and many other agricultural commodities.

These concerns are less important to independent chocolate makers and their customers, because the worst human rights abuses in cocoa production are found in West Africa, which almost exclusively produces the high-yielding but low quality Forastero cocoa variety. Chocolate artisans prefer to work with the Criollo and Trinitario varieties for their superior flavour, smell and texture, and these are mainly produced in Latin America and Asia.

Because chocolate is a luxury, most aficionados expect the highest quality ingredients and a creative passion on the part of the small-scale chocolate maker. To many of us there is also a bit of magic in this ‘food of the gods’, and when Clarisse Poudenx sneaks up on her melting chocolate in the middle of the night she feels the magic, and it feeds her passion for making great chocolate.