Miss Chi hUa hUa and the Rehab Centre for Animals Addicted to Humans

May 14, 2016

Black or White, Put Some Diamonds on Your Plate!

May 17, 2016Our civilisation is so advanced and sophisticated we need not fear. Alas pride comes before a fall. Dantemag investigates how we are maybe at the same point the Roman Empire reached before the barbarian hordes overthrew it and very nearly destroyed its accumulated cultural treasures. Mario Moniz Barreto sounds the alarm.

by Mario Moniz Barreto

From Alexandria to Skellig Michael

I will never forget how in the opening scenes of “Civilisation”, the seminal BBC 1970s documentary presented by Kenneth Clark, we are transported to a tiny island – more a rocky outcrop – a few miles off the west coast of Ireland named Skellig Michael and we are told that the roots of our civilisation as we know it were rescued there by a handful of religious men who kept on copying stunningly illuminated manuscripts as well as the holy texts. They had escaped the uncertainty and destruction which had prevailed within a stone’s throw of the main metropolis of the ancient world.

Like a frail umbilical cord, our connection to the inheritance of the ancient world, with their ideals of justice, reason and physical beauty survived.

Civilisation was saved by the thinnest of margins. It is still possible in 2015 to access most – and in some cases all – of the writings of the ancient world’s scientists, poets, philosophers and to appreciate some of their artists’ sculptures, mosaics and ceramics.

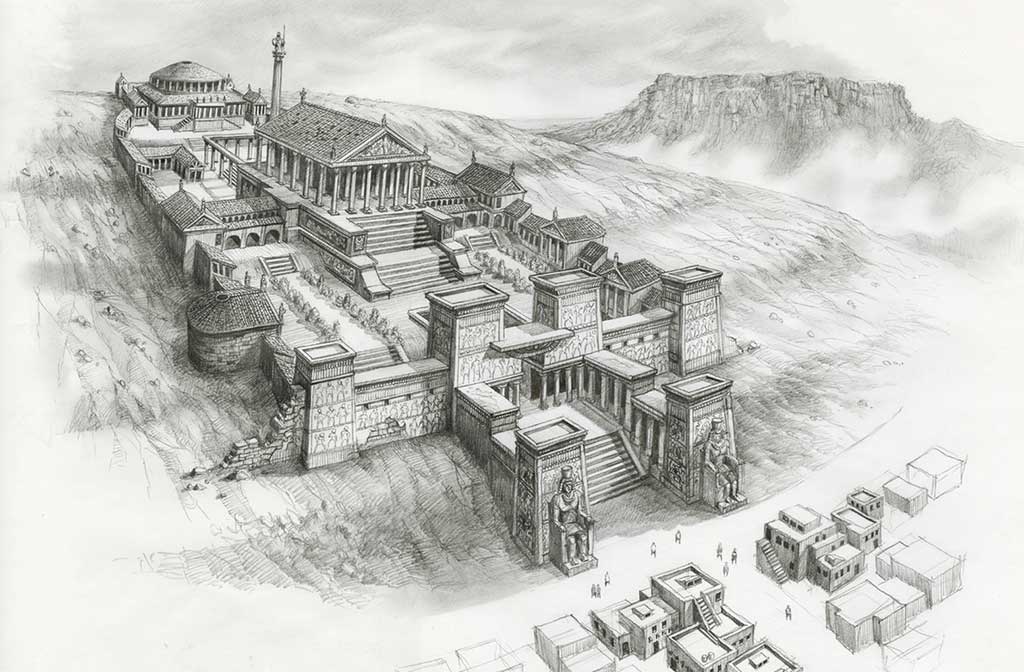

Great Library of Alexandria

How did we get to a point where a centuries-old civilisation spanning such diverse regions, peoples, climates was toppled by a technologically inferior horde?

Maybe Cavafy’s “Waiting for the Barbarians” poem provides us with some clues about that end-of- empire malaise:

As Kenneth Clark puts it: “Civilisation, in order to thrive, requires not only at the very least a modicum of prosperity and time for the enjoyment of those very material goods, but confidence. The same type of confidence that a successful lover usually has. With that comes sometimes overbearing, other times conquering and boundless energy”

This was the type of energy that produced the wondrous achievements of our egregious forefathers, as well as the industrial, medical, or political conquests of more recent times.

Maybe man is arguably living through another similar period in history when there are so few wars, in which violence has, as magisterially conveyed by Steven Pinker in “The Better Angels of Our Nature”, diminished to a “newsworthy phenomenon”, and a world where so few have died from communicable diseases as is the case at present. And yet, there is a strange whiff of malaise in the air.

Around the world there are reports of an increasing taste for a return to nature and for home schooling; more and more parents who opt out of vaccinating their children and children of westernised immigrants who escape to fight alongside obscurantist forces abroad and die alongside them. And all the way through there is a common feeling that there is nothing one can do to achieve a fairer distribution of the wealth we are all still churning out.

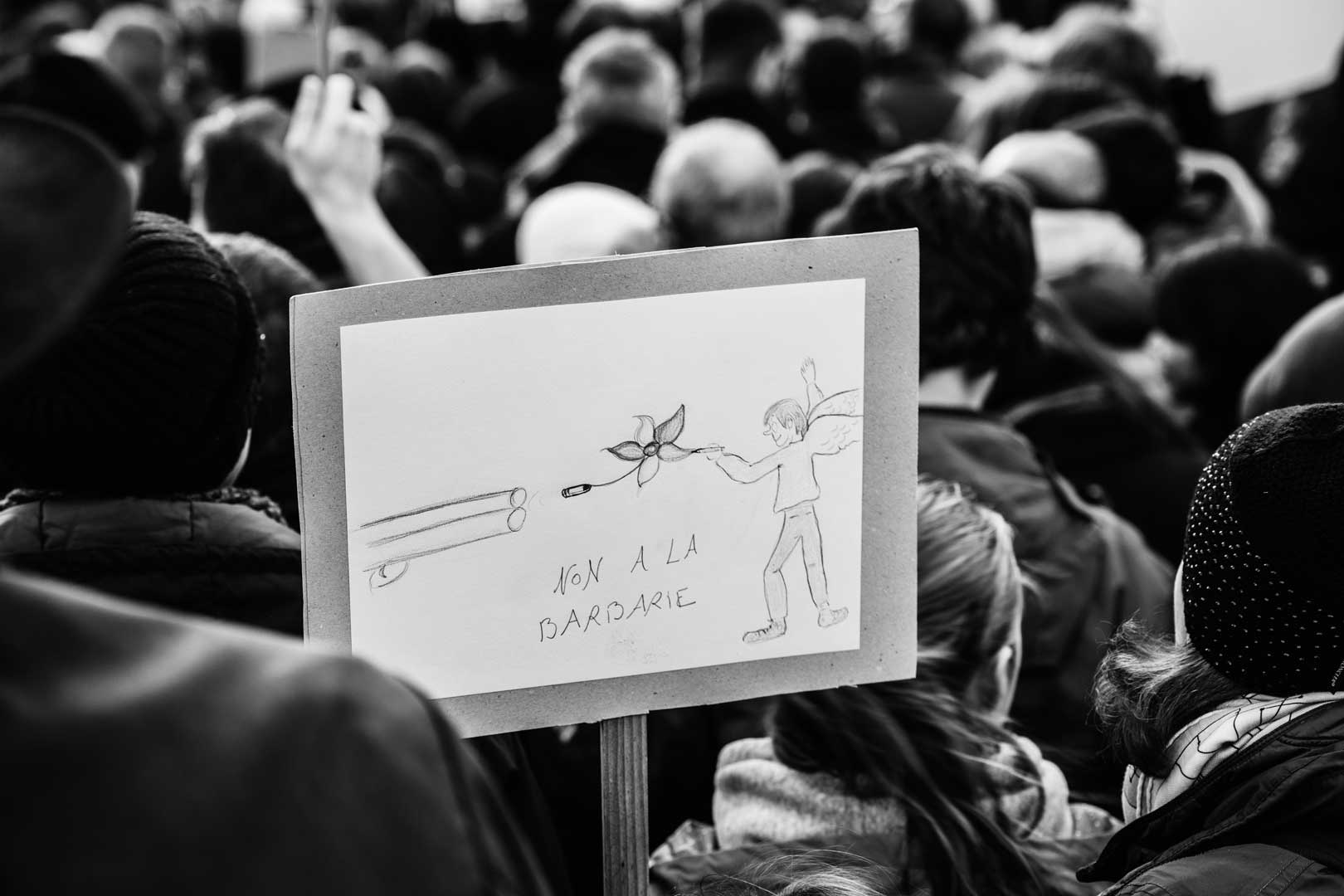

Protest organized by Assn of Nigerians in Alicante

All these trends point not only to a worrying detachment from the essentials of the core values of how we are structured as political and cultural entities – namely,states, but also to a nearly metaphysical curiosity about how it would be to live outside and apart from civilisation. And yet to quote Kenneth Clark once again: “all evidence suggests that the boredom of barbarism is infinitely greater. Quite apart from discomforts and privation there was no escape from it. Very restricted company, no books, no light after dark, no hope”. Maybe one could add to Clark’s construct, that hope is as important to a civilisation’s renewal and strength as confidence and energy.

Fear of the future, longing for the past and how evolution can be circular.

Schopenhauer’s ‘bedenkenlos’ optimism, meaning an ‘unscrupulous’ form of optimism, verging on the irresponsible, should not push us in the opposite direction: that of a self-defeating stance. As Marc Auge says in “The Future”, the uncertainty of what is to come, compounded with negative present occurrences can arouse “every hope and fear”.

Interestingly the time we live in bears striking resemblances to those long centuries that witnessed the birth, apogee and fall of the Roman Empire.

Foreign threats that already are with us

Safety-wise, although no power in particular poses an existential threat, a string of foreign states and more or less diffuse entities wage wars of attrition, either on us, or on our allies. Look no further than what ISIS is doing in the wake of Al Qaeda and some ill-advised Western interventions, or Boko Haram in Africa. Were we Romans, we would call them Vandals, Goths, Huns, or just plain Barbarians – which coincidentally they really are much more so nowadays than then.

If one reads the spirited study by Ferdinand Mount of “How the Classical World Came Back to Us” it is surprising to find out how it could be argued that the nearly 1,300 years since the fall of the Roman Empire, were, in a way, nothing more than an intermission in the “traditional ways to be human”.

European Parliament Brussels, Belgium

Religious Morality has abandoned our bodies as well as our sexuality

We are once again obsessing with the shape of our bodies as well as with hygiene. Increasingly, publicly and in the privacy of our bedrooms, sex is no longer a (religious) moral issue. Instead it is regulated by social norms that bear no connection to sin and guilt. As Christian diktats got stricter and more detached from real life, so we all started edging away from them, regardless of which letter we identify more with across the H, L, G, B, T spectrum.

Were it not for technology, how innovative would the basics of our science and system of state be?

Were one to look at science we would find it difficult to distinguish between some of the theories on the infinity of space and time of Hawking and those of a Pre-Socratic, like Anaximander, or between Darwinian evolution theory and first century BC Siculus’s account of how we all dragged ourselves out from a swamp and evolved…

If we focus on philosophy and politics and read the following passage:

“Not out of fear but out of a feeling of what is right should we abstain from doing wrong (…) To be good means to do no wrong and also, not to want to do no wrong (…) it is good deeds, not words that count (…) The poverty of a democracy is better than the prosperity which allegedly goes with aristocracy or monarchy. Just as liberty is better then slavery (…).”

That was neither written by Saint Augustine, nor by Montaigne, nor by any of the prolific American “Founding Fathers”. Democritus is the classical ancient behind this extract of philosophy that is remarkably contemporary and secular.

Fernando Pessoa

George Seferis

There are other classical political documents holding striking resonances to the present mood. None more so than the Athenian Pericles’s address: “… Our form of government is called a democracy because its administration is in the hands, not of a few, but of the whole people. Election to public office is made on the basis of ability. No man is kept out of public office by the obscurity of his social standing because of his poverty. And not only in our public life are we free and open, but a sense of freedom regulates our day-to-day life with each other”

We would have to wait all the way until the eighteenth century, to Condorcet, Voltaire, or with some of the American Revolutionaries for us to arrive once again at this level of theorising on the democratic construct.

Atheists and creative sects battle it out

It may not be only in politics where so-called mainstream parties are losing votes and therefore power. Mutatis mutandis, the same is happening with religion. Just as in ancient Rome, where any city in the empire, as long as it conformed to the rules, could venerate whatever kind of deity, when any school of thought drew little more than an incredulous frown, so today secular states are putting on an equal footing every kind of faith, be they druidic or even more recent beliefs that mythologise space invaders. This, at a time when some of the mainstream religions attempt to regroup, either resorting to dogmatic purity or modernising somewhat in order to stem the bleeding away of their faithful.

The non-believers or atheists, are, as Dawkins puts it, proudly standing “tall to face the far horizon” unaided by metaphysical creatures “for atheism nearly always indicates a healthy independence of mind and, indeed, a healthy mind”.

It is extraordinary to think how from the first doctrinaire discussions within the faiths our world has reached a point where, to quote Martin Amis, “opposition to religion already occupies the high ground intellectually and morally.” A world where the more we understand nature, the more we naturally revere it in a pantheistic way, as Einstein would have us believe.

Are we fast becoming twenty-first century animists, then? Pessoa wrote: “God is God’s best joke”. And now some of us have just got the punch line.

The parallels between us now and us then go on.

The elephant in the room is the possibility that now that we are back as we were then we may be facing the same level of destruction and oblivion and be about to embark on nearly 1,300 years of cold nights and barren days.

Skellig Michael

From Brussels to Skellig Michael?

Maybe it is all due to the surprisingly stronger influence of all those deterministic materialistic currents of thought. Or instead it is the fact that humanity has indeed been getting a better deal since The Enlightenment. Whichever it is, ever since the 1950s, the Western world above all, has been convinced that it has reached an Arcadian model of progress and living. Save for a few hiccups or blips, this has been for some time, true.

This path to progress which has involved reconnecting with our ‘white-marble-under-clear-blue-skies’ ancient past is not without its risks, for, as Claude Lefort puts it: “la démocratie est le seul régime tragique”. An integral part of the systematic doubt-everything-in-our-world is the possibility for, if not self annihilation, then, at the very least, self challenge that can, as it did in the past, tip the balance of democracy.

The challenges ahead seem a lot like the downfalls from the past. The view from Berlin to Athens, from Paris to Madrid, from Helsinki to Lisbon, albeit with different points of origin, looks at the end of journey and that place does not, for now, look all that good.

The southern European perspective is that of an impoverished present without any improvement in sight, while the northern one is of a sheltered present with an impoverished horizon. No one dares to challenge this deadlock; no one wants to renegotiate the grand wager which opened up our borders to nation-effacing freer trade with each other and ‘others’ in the expectation that as our goods would flow, so would our values and our democracy. So far that goal has been as elusive as it has been detrimental.

A present without ‘romanitas’ compounded with a future where hope is replaced by fear are two of the elements usually identified by historians to explain the collapse of civilisations. Fear and lack of confidence reduce the motivation to build, make people less prone to plan ahead and turn a welcoming smile into a suspicious twitch.

I will leave you with the words of Nobel Laureate George Seferis, a poem which should resonate around our world otherwisewe shall all have to try and clamber onto rocky outcrops like Skellig Michael:

“The poem is everywhere. Your voice sometimes travels beside it like a dolphin keeping company for a while with a golden sloop in the sunlight, then vanishing again.(…) he who has loved knows this; in the light that other people see things, the world spoils; but you remember this: Hades and Dionysus are the same”.