Ewa Wilczynski, The Birth of a Venus

August 16, 2016

Like a Dog With Two Wheels – The moving story of an Italian who gives disabled animals a second chance.

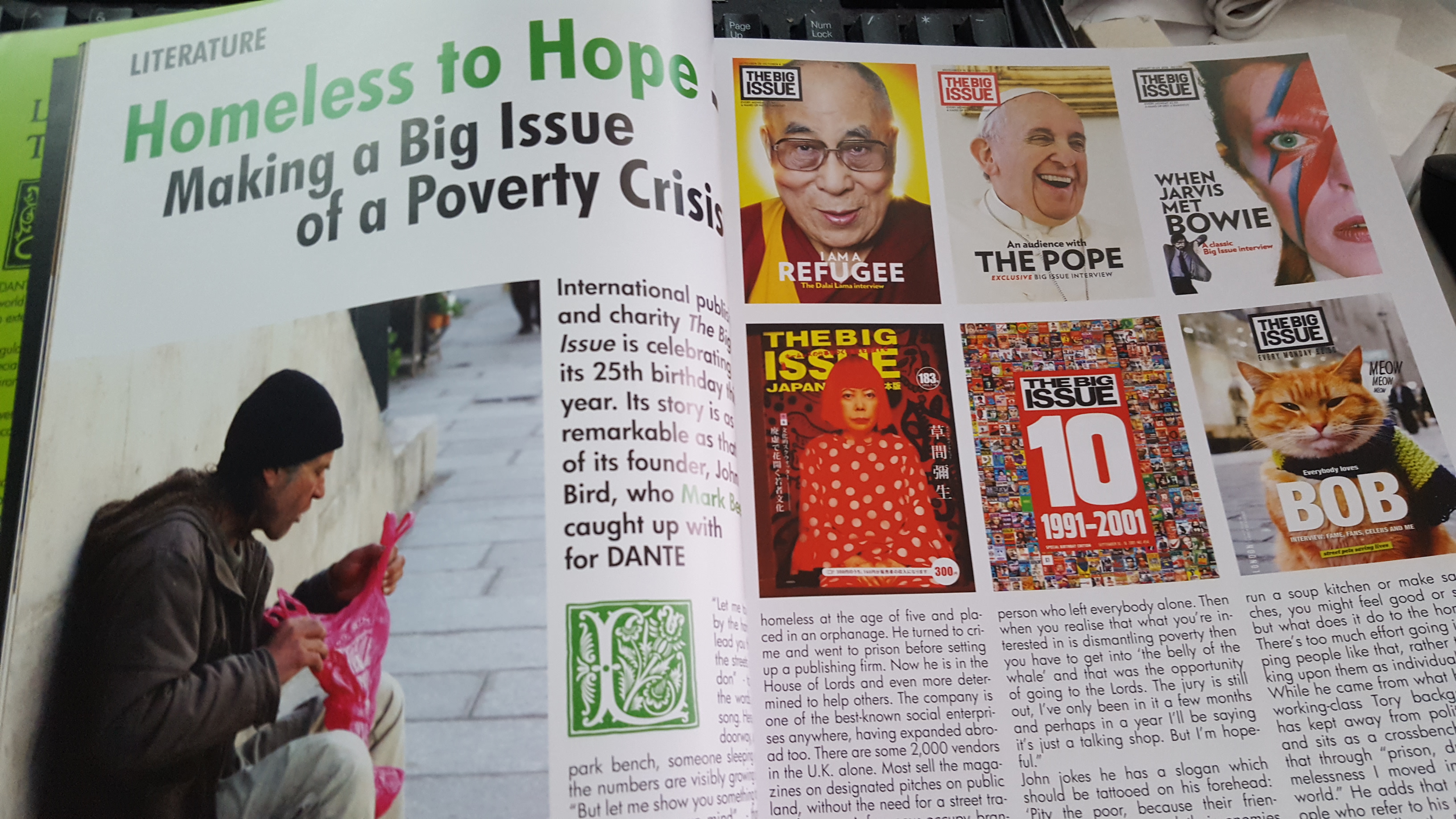

September 1, 2016Making a Big Issue of a Poverty Crisis

International publisher and charity The Big Issue is celebrating its 25th birthday this year. Its story is as remarkable as that of its founder, John Bird, who speaks to MARK BEECH for this report.

“Let me take you by the hand and lead you through the streets of London.” (To quote the words of the song.) Here in this doorway, on that park bench, someone sleeping rough; the numbers are visibly growing again.

“But let me show you something to make you change your mind.” (Thank you Ralph McTell.) Look at the numbers of Big Issue vendors: people who are escaping from the poverty/ homeless trap by selling a magazine. The company is helping people to help themselves and the sellers are “getting a hand-up, not a handout.”

That slogan is the mantra of John Bird, 70, The Big Issue’s founder. He is driven by first-hand experience of poverty and social deprivation, having been homeless at the age of five and put in an orphan’s house. He turned to crime and went to prison before setting up a publishing firm. Now he is in the House of Lords and even more determined to help others. The company is one of the best-known social enterprises anywhere, having expanded abroad too. There are some 2,000 vendors in the U.K. alone. Most sell the magazines on designated pitches on public land; without the need for street traders’ licences. A few now occupy branded points on station concourses. All buy the magazine for £1.25 and sell it for £2.50.

That slogan is the mantra of John Bird, 70, The Big Issue’s founder. He is driven by first-hand experience of poverty and social deprivation, having been homeless at the age of five and put in an orphan’s house. He turned to crime and went to prison before setting up a publishing firm. Now he is in the House of Lords and even more determined to help others. The company is one of the best-known social enterprises anywhere, having expanded abroad too. There are some 2,000 vendors in the U.K. alone. Most sell the magazines on designated pitches on public land; without the need for street traders’ licences. A few now occupy branded points on station concourses. All buy the magazine for £1.25 and sell it for £2.50.

Could John imagine that he would have ended up in the House of Lords? “Not really, no!” he says in an interview. “My intended path was to overthrow capitalism, first of all to be a good Catholic boy and then to be a Nazi, then to be a Marxist and then to be a small business person who left everybody alone. Then when you realise that what you are interested in is dismantling poverty then you have to get into ‘the belly of the whale’ and that was the opportunity of going into the Lords. The jury is still out, I have only been in it a few months and perhaps in a year I will be saying it is just a talking shop. But I am hopeful.”

John jokes he has a slogan which should be tattooed on his forehead: “Pity the poor, because their friends are dreamers, and their enemies are wolves.” Where did the quotation come from, I ask. “I made it up myself,” he responds: Bird is known for his writing, such as The Necessity of Poverty, a trenchant attack on conventional thinking. He is adamant that soup kitchens don’t help the situation: people need to be got back on their feet not encouraged to take. “If you run a soup kitchen or make sandwiches, you might feel good or saintly, but what does it do to the homeless? There is too much effort going into keeping people like that, rather than looking upon them as individuals.”

John Bird and Gordon Roddick at House of Lords event for Big Issue vendors

While he came from what he calls “a working-class Tory background” he has kept away from political parties and sits on the crossbenches. He says that through “prison, drugs and homelessness I moved into a different world.” He adds that most of the people who refer to his title (Baron Bird, of Notting Hill in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in full) do so to “take the piss out of me” and that’s completely fine. John’s maiden speech in parliament generated some headlines when he said “bugger,” which doubtless woke up some of their noble lordships, but that was in the course of an impassioned and reasoned call for ways to address poverty. His 13-minute address was warmly described by one peer, Lord Patel, as the most eye-opening in decades, and he wasn’t just referring to the “bugger”.

John recently took 40 magazine vendors into the Lords for a tea party and said their reaction was moving: “Most of them had never, ever, ever had anyone pat them on the back for anything, or fussed over them or made them feel important. The Big Issue is a bit of a family to them and then their ‘dad’ takes them into the House of Lords, and there were many tears. It is a place of privilege but it also has to be place of opportunity.”

How does he see The Big Issue’s progress? In John’s first editorial, he commented that hopefully the magazine would do itself out of business as homelessness became history through action by governments, charities, non-government organisations, individual homeless people themselves and the general public. “That hasn’t happened, obviously, over the last 25 years and that’s largely because much government activity around the subject is self-defeating. About 70 to 80 percent of the money spent on poverty is spent on emergencies, or keeping things in a holding pattern, stabilising people, treading water – with very little on prevention and cure.”

![image[55] (1) copy](https://www.dantemag.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/image55-1-copy-300x106.jpg) Between 2014 to 2015, Bird quotes figures showing the U.K. has seen a 30 percent increase in homelessness; while since 2010 estimates have increased by 102 percent for the number of rough sleepers. “There was a time when there were a couple of thousand people sleeping rough in London’s West End and now there are hundreds, but numbers are rising again.”

Between 2014 to 2015, Bird quotes figures showing the U.K. has seen a 30 percent increase in homelessness; while since 2010 estimates have increased by 102 percent for the number of rough sleepers. “There was a time when there were a couple of thousand people sleeping rough in London’s West End and now there are hundreds, but numbers are rising again.”

John measurers success by the difference he makes in the lives of workers, moving them clear of the dangers of exploitation, drink, drugs, mental and physical health problems, selling their bodies or stealing, preventing them from falling into the arms of the state – and giving them skills which may help them in future.

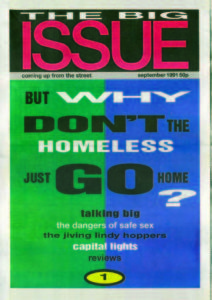

Big Issue – first cover

He is proud of The Big Issue Foundation, the charity set up in 1995 which aims to help vendors to achieve their aspirations and goals and build “life beyond their livelihood,” such as with housing, health, education and more. The Foundation doesn’t duplicate services provided elsewhere and says each “positive outcome” is achieved for an average of £105.

Even more fundamental is Big Issue Invest, also formed in 2005, which has put money into 250 social businesses around the U.K., “and their remit is to prevent the next generation of Big Issue vendors. Even that is just a drop in the ocean, because you have got to get into the mind of the government departments, which are the ones where all the poor thinking is.”

He knows it would be ironic if these initiatives were so successful that the magazine had no vendors, but notes that in the first five years of its existence there were a lot more, because so many were without accommodation.

How can other people help?, I ask. John replies that they may choose to get involved in events (such as “The Big Sleepout” at St. John’s Church, Waterloo, on November 25), but above all he hopes people will buy the publication, read and enjoy it – “I get very disheartened when people say to me, ‘oh, I buy the paper but I don’t take it and say it can be sold on to someone else.’ Anyone who does that is turning them into a beggar. I brought them to the marketplace and turned them into a worker.” But what he really wants is to see a return to co-operative ideas: “We need to change the way we buy stuff, we have to have social Amazons and all that.”

Lord Bird is forthright, outspoken, no-nonsense, gruff – caring and likeable. You can tell he cares about the people he works with.

It he had his time again, John says he would have really “burned the candle at both ends” so he could understand capitalism better and how to improve society. Simultaneously he is “obsessed with art,” having gone to art school after his time in prison. “If I couldn’t become a new leader around understanding how the market works to teach other people, then I would be Britain’s answer to Picasso and all those people.”

Australia cover

John says that when not working “I’ve been writing a book for 20 years, which is my way of learning how to write. It’s about my struggle with idealism. The other thing is, I draw and do everything from trees to naked women, and I had an exhibition a few years ago, ‘all grasses, arses and trees.’ I give all the money away, I don’t need the money. – When I say I don’t need it, I could do with a little, because I could buy a better bicycle.” He lives in hope someone will steal his pushbike so he can upgrade to a newer model. John lives in a village near Cambridge with his third wife, Parveen. They have a camper van for holidays: “I have a very young family, a nine-year-old and an 11-year-old – I’ve also got a 38 year-old and a 40 year-old and a 50-year-old!” John has absolutely no plans to retire, and jests “I hope to die on the job!”

Shortly after the interview, I am thinking of how John has helped the likes of the man without pride in the Ralph McTell lyric, “Hand held loosely at his side, yesterday’s paper telling yesterday’s news.” I see my regular Big Issue seller, who today has a spring in his step and a new edition. A few years ago, he’d have been in the song. Now he has a smile and hope for the future. Thank you Ralph McTell sure, but, thank you John Bird especially.

THE FULL INTERVIEW APPEARS IN THE PRINT EDITION OF DANTE MAGAZINE ON SALE IN WH SMITHS IN AUGUST AND SEPTEMBER

Please subscribe online or buy us in larger WHSmiths

The article in print

John Bird now

John Bird by Martin Gammon

Young John Bird