From Wounded Knee to Musical Wonder

September 15, 2016

Andrea Bocelli – “If God Could Sing…”

October 1, 2016Translation is a concept known to us all. So is the concept of conveying ideas to people with different cultures, beliefs or languages to our own. What gets lost and misunderstood in translation matters for a multilingual publication like DANTE.

Dr. Eliana Corbari explains

Translation is a bridge between people who speak different languages. But it is also a bridge crossed by poets, musicians, and artists when they put emotions into words, sounds, and images. We all cross the bridge of translation more often than we may think. It is about difference and about movement; with translation we travel in space between different countries and cultures and we travel in time between the past and the present. Sometimes we try to do both, to move in space and in time. This is precisely what I attempt as an academic researcher in Medieval Christianity. It is often a conversation stopper when I tell people that “vernacular theology” is my main re-search interest. If they show any curiosity, I have to consider the questioner in order to make my answer intelligible, find a common language and perform an act of translation. This discipline has the act of translation at its very heart. It is particular to a time and place and moves beyond the academic world. Both sides must be open to learn from each other. Some of these qualities do not pertain only to vernacular theology. Yet it is important to recognise vernacular theology as a different and significant component of the Christian theological tradition.

My book “Vernacular Theology” focuses on the transmission and audience for Dominican learning in Italy prior to the Council of Trent (1545-1563), which was a milestone in European culture. Some would say a stumbling block. Since my book’s publication in 2013, I have developed further insights from encounters within and without the academic world, so that now I place translation at the heart of vernacular theology. Here I intend to give an introduction to the subject and explore the relationships beyond the Middle Ages.

Concepts matter, they matter because they inform how we think and act. They have the power to change how we interact with the world. Being aware of the concept of vernacular theology may transform the way to consider others from the past. I’m saddened that the writing and legacies of many medieval women in Christian Europe have largely been ignored so that even some feminist theologians rely exclusively on the authority of male authors.

There is consensus among medievalists that vernacular theology represents the third dimension to medieval Christianity, alongside monastic and scholastic theology. The languages of the Bible were verbalised, first into Latin, and then into a variety of local vernaculars. The 4th century Latin translation of the Bible, known as Vulgata, represents the act of putting into the vernacular the original languages of Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek, because Latin was, in effect, the Roman vernacular of the time. Indeed Christianity is the only monotheistic religion to accept its sacred texts in translation. Even before the counter-reformation (marked by the Council of Trent), translations of the Bible in the vernacular circulated in parts of Europe. Many people who did not know Latin were able to read and listen to the Bible in their local languages.

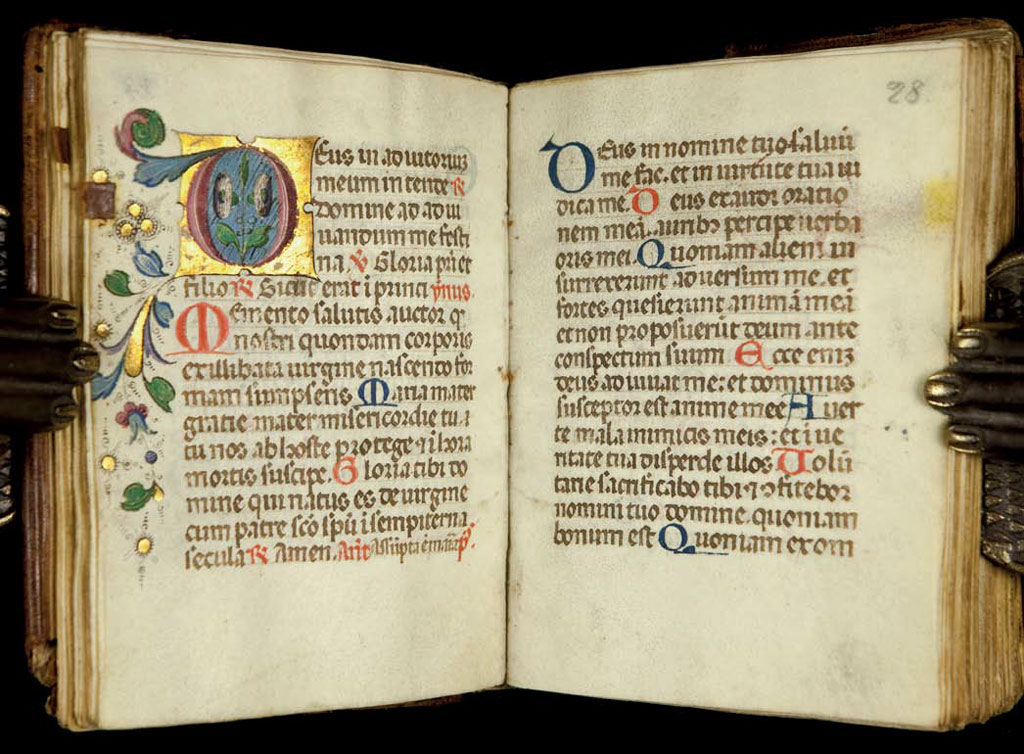

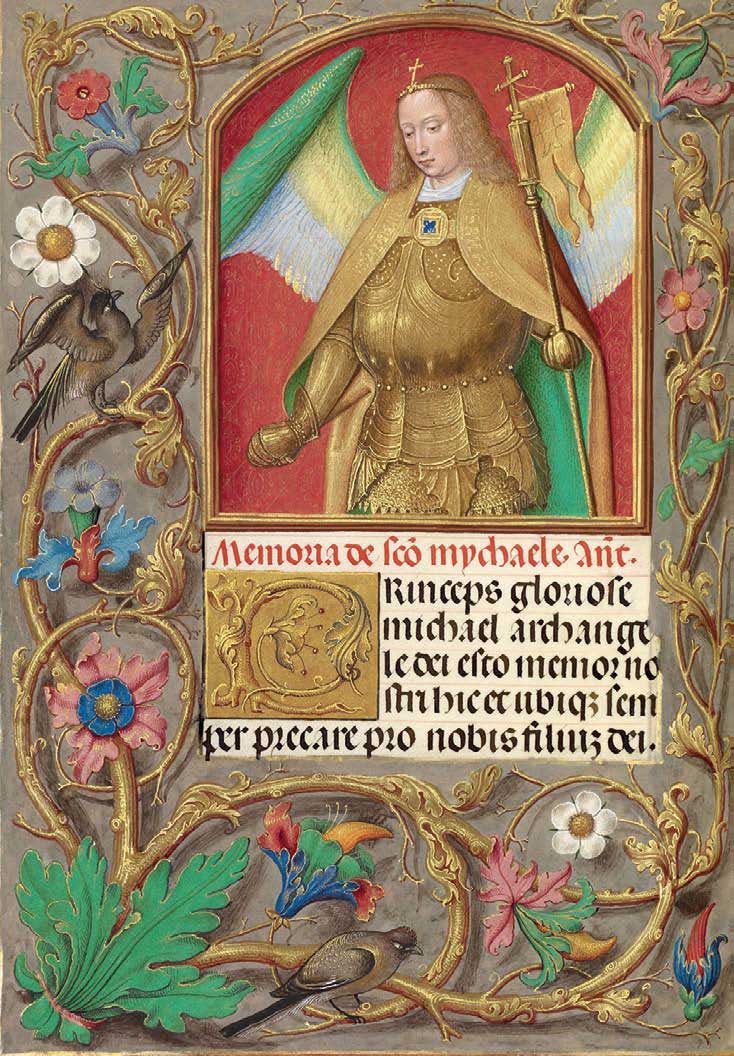

The tradition of vernacular theology is more difficult to de-fine than monastic or scholastic theologies, partly because it is “less technically precise and identifiable” according to Bernard McGinn, (“The Changing Shape of Late Medieval Mysticism” 1996). Cathedral schools, which developed into universities, were the basis for scholasticism, while the monasteries and convents gave rise to monasticism. Vernacular theology does not mean theology for the ignorant masses, nor theology written in the vernacular. For instance, some texts written or translated into Latin, such as the lives of the saints, the “Liber Lelle” by Angela of Foligno, or the “Revelationes” by Birgitta of Sweden, are vernacular theology. Its main literary genres may be identified especially with sermons, poetry, laude, reportationes (sermons recorded by the audience), letters, hagiographies (lives of the saints), plays, and treatises (see Carlo Delcorno’s “The Language of Preachers: Between Latin and Vernacular” 1995). But it includes media other than the written word, such as visual arts or music.

Vernacular theology was a term coined by Ian Doyle in the 1950s and brought to prominence especially by Nicholas Watson and Bernard McGinn in the mid-1990s.

In 1991, while leading the Congregation of Doctrine and Faith, Joseph Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict XVI, said with reference to the writings of medieval women such as Birgitta of Sweden, Angela of Foligno, and Catherine of Siena, to name but a few, that it ought to be considered theological rather than “simply be labelled and filed away as ‘edifying’.” Ratzinger describes these and other female authors as theologians. These medieval women tend to underestimate their intellectual content (see Nicholas Watson’s “Censorship and Cultural Change in Late Medie-val England” 1995). For the same reason, vernacular theology does not equate to “popular theology” or “pastoral theology”.

Women had leading roles in monastic theology, but when universities became the new centres of learning, women became widely excluded.

In the Middle Ages, neither scholastic nor monastic theologies could remain the preserve of those at universities, monasteries or nunneries. A new form of Christian learning was developed by women and men in private dwellings and public squares. Thus, vernacular theology was a response to a need to translate and re-elaborate an ‘incarnate’ theology – that is, one taking place in the realm of human experiences, thereby existing in body and soul and in a particular time and place. A need which was signalled and enriched as a result of collaborations between men and women, probably one women above all wished for, as they had become excluded from most formal theological studies. Indeed it was only in the last century- to quote English examples – that women were finally officially allowed to study and graduate from the universities of Cambridge or Oxford.

Vernacular theology arises from the secular meeting the sacred and it thrived among women and men in the late medieval period. It essentially sprang from a desire to give shape to the relational spaces between theory and practice; between laywomen, laymen and the clergy creating communities of authors, readers, commissioners, and protagonists of these theological narratives. Women were often at the forefront of their transmission. Vernacular theology can be found in sermons, poetry, laude, reportationes (sermons recorded by the audience), letters, hagiographies (lives of the saints), plays, treatises, the visual arts and music. Many books in the Bible, notably those in Hebrew, are written as poetry. Like poetry, proverbs are written in rhyme. The translation of proverbs, as for the translation of poetry, is notoriously difficult and stubborn in their incomplete-ness. This quality is acknowledged by anyone who has done translation work. Jacques Derrida says that the translation of poetry is like “a hedgehog that is crossing the road and, in trying to avoid getting squashed, curls up into a ball to protect its heart.” (See “Che cos’è la poesia”, 1991). An Italian proverb goes: ‘Dal dire al fare c’è di mezzo il mare’, which can be literally translated as ‘Between words and deeds there lies the sea’. This is a sea to be navigated rather than an unbridgeable gap. This is also a sea of ink in Italian vernacular theology that, with the exception of pinnacles of poetry such as that of Dante, or well-known saints such as Catherine of Siena, is still largely unexplored in the English language.

If the movement between words to deeds is conceptualised as a form of translation, its incompleteness becomes intrinsic. Such incompleteness is able to be improved upon insomuch as one accepts that words and deeds, thoughts and actions, are connected with mutual openness to revision. Going from words to words, words to deeds, and deeds to words are part of circular acts of translation. The intermediary stage, the gap between each, can be understood as a bridge which is the task of translation.

If the movement between words to deeds is conceptualised as a form of translation, its incompleteness becomes intrinsic. Such incompleteness is able to be improved upon insomuch as one accepts that words and deeds, thoughts and actions, are connected with mutual openness to revision. Going from words to words, words to deeds, and deeds to words are part of circular acts of translation. The intermediary stage, the gap between each, can be understood as a bridge which is the task of translation.

David Burrell says that “Doing theology, like conversing with friends, is akin to the process of translation” (“Friendship as Ways to Truth”, 2000). It requires a continuous openness to mutual listening with the transformative goal of mutual change. This task requires desi-re for truthful learning and, above all, humility – the highest monastic virtue in medieval times.

The result attempts to make visible the invisible love of God, while existing in the hotchpotch of very different lives and languages existing outside the cloisters and the universities.

For some people, it may be more comfortable to converse with those who share similar views and culture, not least because it confirms their own sense of identity, but our times require us to move beyond our comfort zones, beyond tolerating the stranger, towards actively seeking conversations with tho-se who are different to ourselves. These conversations are taking place nowadays in some universities where students and lecturers come from various countries and backgrounds as well as at the European Parliament and the United Nations. However, since their members probably come from the higher social and professional classes, this is a limitation in terms of difference but, despite that, different languages and cultures are, nevertheless, meeting and hopefully learning from each other. It is not coincidental that these institutions share a desire for peace. Publications like DANTE play their part by publishing international writers in different languages.

The time is ripe to learn from vernacular theology and move beyond institutions. This is the moment to follow the lead of medieval women and take the creative risk of collaborative translations.