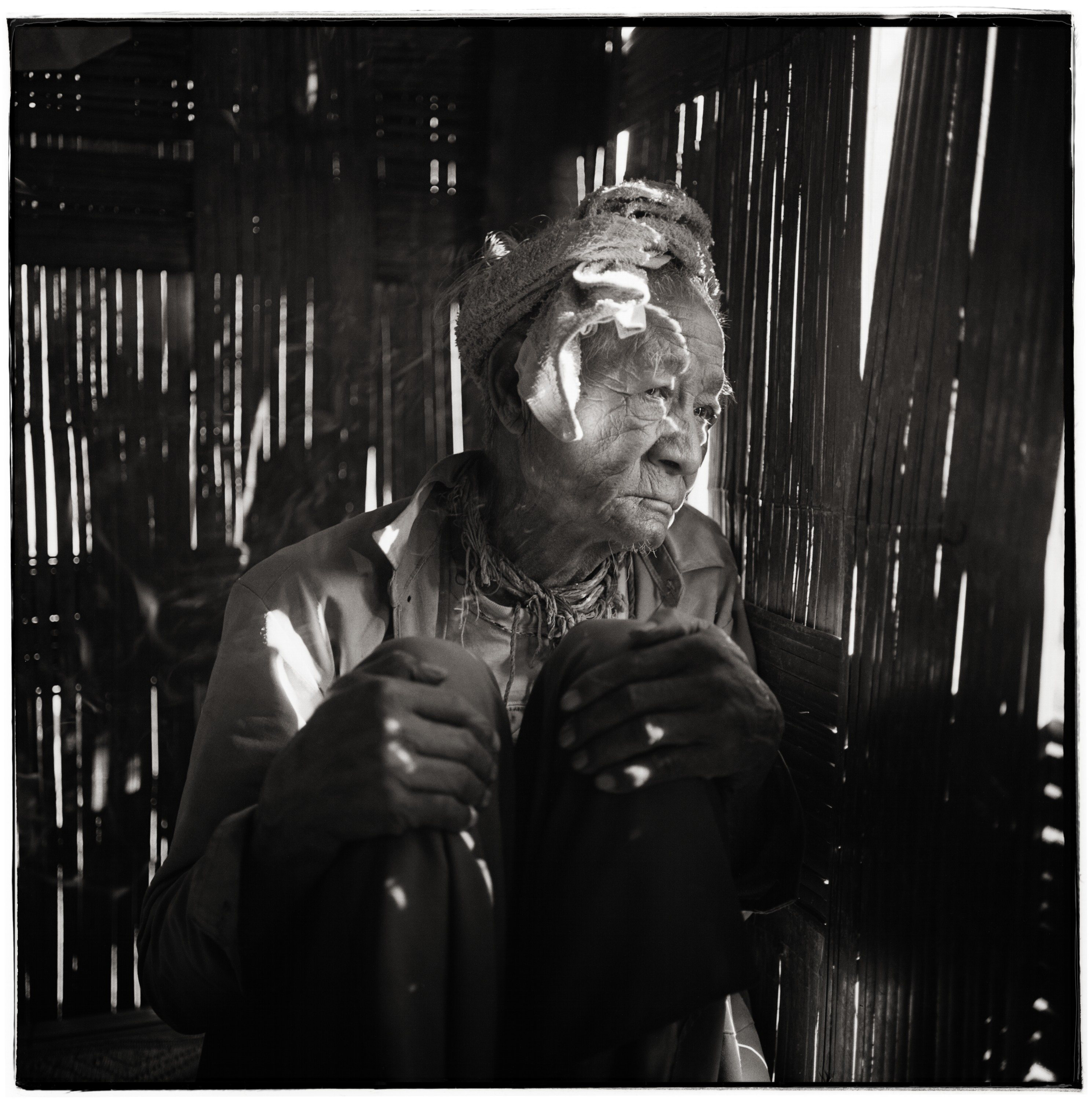

Living With Spirits: Thailand Caught on Camera

April 21, 2017

French Election Time and Democratic Spring: Of Fascism and Future Hopes Worldwide

April 23, 2017Marilyn Perry has won acclaim as a painter – a late flowering after a career as one of the world’s top art historians. DANTE’s Editor Mark Beech talks to her about her visionary work.

THIS IS A VERSION OF AN INTERVIEW THAT APPEARS IN SLIGHTLY DIFFERENT FORM IN THE APRIL-MAY 2017 ISSUE OF DANTE – AVAILABLE IN LARGER W.H.SMITHS AND INDEPENDENT NEWSAGENTS IN THE U.K. OR ON SUBSCRIPTION (6 BIMONTHLY ISSUES DELIVERED TO YOUR DOOR)

DANTE IS ALSO ON PHONE APP WITH SELECTIVE ARTICLES SUCH AS THIS ONE ONLINE FOR FREE AS A TASTER

Marilyn’s out-of-town studio

Try to capture the uncapturable in nature. Look at landscapes that constantly change and can hardly be photographed. Incoming tides twinkling with moonlight; rushing water that never stands still; dense fog sweeping over headland, icy snowstorms; fiery lava slipping down a hillside; autumn sunshine that blazes for bare seconds. Not many artists have well captured the evanescence of the elements. Marilyn Perry is one.

*

“Last Light”

About a decade ago, I was visiting New York for business. A colleague helpfully said: “Why don’t you stay at my friend Marilyn’s place? She’s out of town for a week at her studio upstate. Only thing is, it’s completely full of her paintings. She’s an artist.”

So I got the cab driver to drop me off at the storied Ansonia where Marilyn still lives. For those who don’t know, the Ansonia is one of Manhattan’s legendary mansion blocks. It is on Broadway and West 73rd, known as the home of everyone from Babe Ruth to Angelina Jolie.

My jaw dropped when I entered the apartment, which was more of a gallery. It was indeed lined with paintings – mainly stunningly good, mostly semi-abstract. I remember that it was a balmy summer day.

“Ice Flow,” 2007

I had bought some iced coffee and bagels from Zabars up Broadway first and sat down with a colleague to marvel the paintings and said, “wow, who is this Marilyn?” This work was all obviously done fast in acrylic, with the artist probably enjoying the movement of paint and seeing where it took her. This looked like the youthful work of someone with a fresh eye and with the verve to take risks – risks which for the most part paid off.

*

I soon discovered that Dr. Marilyn Perry (who is now 77) was a scholar of Italian Renaissance art.

Marilyn lived, wrote and lectured in Europe from 1965 to 1981, mainly in London, Rome and Venice. From there, she moved into cultural philanthropy. In 1984 she became President of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, devoted to preserving European art, and in addition in 1990 she became Chairman of the World Monuments Fund, building its campaigning and fundraising and saving sites from Cambodia to Guatemala. Among her proudest achievements is helping to protect the Qianlong Garden in the Forbidden City, a retreat which was largely abandoned in 1924.

Marilyn Perry in her studio

As she says in an interview with me, “I didn’t start painting until I was in my early 60s, but I am an art historian by training, so I have looked at and thought about art my entire adult life.”

“Water Surface II,” 2008

The painting came about like this. She enrolled for classes for a few hours each Saturday with a local watercolour artist near her rural retreat: “I thought I will learn about making art rather than just looking at it. I fell in love with both the process and the challenge.”

Her tutor offered out postcards to the students to replicate, and Marilyn’s very first work was based on this: an autumn landscape with a small house. “It came out pretty well, I was surprised! But what I learned pretty quickly was that I didn’t really want to be taught.”

Over the next five years, Marilyn circled back to painting in her spare time, working through how-to books and carrying paints wherever she travelled. “It was not that I was going to set up an easel and paint Venice, it was just that it was fun to play with.”

“Extinct Volcano”

Marilyn had a short enforced break in 2005-6 after contracting Lyme Disease. She had to overcome facial paralysis and difficulties with balance and vision. Painting helped her recovery. Still, when Marilyn retired in 2007, the idea was still gradually creeping up on her. She could have done more academic work, or consulting, and gradually realised what she liked.

*

Back to the Ansonia a decade or so ago and my iced-coffee drinking before heading out onto the hot streets below.

Marilyn may blush at the comparison, but my friend said that some of her forestscapes had a hint of Hockney; the washes of cloud and mist recalled Turner; the deep mossy pools mirrored Monet; the seascapes were like sketches by Winslow Homer or Ivan Aivazovsky. Over the next few years, as I came to know Marilyn, I realized that she is her own woman and just painting as she knows how, not emulating but just trying to capture her vision.

“Headland Fog,” 2009

When a painter gets raves it is often shortly after they leave art school. (One might recall the ironic Roy Lichtenstein picture with the caption “Why, Brad darling, this painting is a masterpiece! My, soon you’ll have all of New York clamouring for your work!”).

Obviously Marilyn is being noticed a little later in life and with no formal training in painting. Being this way obviously helps in her case.

One of her works was shown at the National Academy Museum on Fifth Avenue; and after shows with good sales, including at Rogue Space Gallery and 25 CPW, some of her paintings hang in homes that also have Old Masters by leading names. I declare an interest, of sorts, in that I happily have three of her pictures, though sadly no boldface Old Masters.

“I never related to sitting down in front of a landscape and trying to paint it,” she says. “I also discovered that I didn’t want to be an oil painter. It was too complicated. I took to acrylic painting, which has more intensity and more saturated colour, but can be used like watercolour.

“Green Pond”

“I went to semi-abstract pretty quickly too. I like the idea of painting something that has a recognisable response to something in the natural world. I found my subject pretty early on. I had never tried, for example, portraiture.

2009 – INCOMING TIDE, acrylic on paper, 22 x 30 in.

“I liked the idea of evoking a natural world basically in constant motion in a static medium, so I took to painting water and sky and other aspects – anything that can be felt as well as seen. To try to capture the feeling that comes from walking along the wet beach or looking at the world after a downpour, the way the sunrise comes up over the sea, any number of subjects or subjects of that ilk, but never with a specific site or date or place in mind.

“I don’t use photographs at all. It is more about what emerges on the canvas or the paper or the panel. One of the big questions that is always in my mind, and I am sort of fearless about this, is when I have something that looks pretty good but I am not quite sure about it – then what if I did this – p0ur some white on, or turn it upside down or make it run more. So there is a play element.

“Moonlit Sea,” 2010

“There is no specific composition, ever. It is about capturing what is emerging. Sometimes I lose something that is pretty good. But with the good ones, something totally unexpected appears.”

More recently Marilyn has been experimenting with encaustic painting, the ancient technique of beeswax – “the best manufacturer of encaustic paints in the United States is in Kingston, the county town of Ulster county where I live on the Hudson River. It is just 30 miles away, and they give training sessions. It is a complicated technique where you have to heat the beeswax to at least 200 degrees Fahrenheit. It needs to be ventilated properly because if you heat it too much, it turns to something like nerve gas!”

The ancient Greeks used the wax to coat their boats and then the technique was used for the so-called Fayum portraits from Roman Egypt. These portraits, placed on mummies in the tomb, are now found in the British Museum and the Metropolitan Museum.

The ancient Greeks used the wax to coat their boats and then the technique was used for the so-called Fayum portraits from Roman Egypt. These portraits, placed on mummies in the tomb, are now found in the British Museum and the Metropolitan Museum.

Marilyn points out that because it is a transparent wax, each encaustic coat shows the material below, the pure pigment is outstandingly bright and the works can be polished to look almost like metalwork. The only caveat: with their different layers and textures, it is very difficult to do justice to them in a photograph.

“Orchid,” encaustic, 2016

“Waves”

Of her fascination with water, she says: “It is really quite simple. Particularly with the acrylic, where I put a lot of water with it. I do not particularly use brushes, I use other things, and with encaustics I use a hot knife and a little iron and a tool that blows hot air. You can use bristle brushes, You can’t use synthetics because they would be melted.”

She has got over the initial reluctance that many artists have to selling their works.

“Initially I was starting late in life and didn’t know that I could do it. So each one I did was a kind of miracle. It would be like having children late in life, I think. So I would have these paintings around me that made me feel very good and I wanted to keep them!

“I remember painting one really beautiful picture: it was a very misty seascape where everything worked perfectly for me. It was very much a watercolour style and I framed that picture and I had it in my office at the Kress Foundation. One of the trustees one day said ‘if you ever want to sell that painting, let me know.’ I said that I could not at that moment think of selling it. Sometime later, after I had set myself up as an artist, I got in touch with him and thought if I ask a high enough price, that will be good for moving forward in my new career. That indeed is what happened. The picture lives in San Francisco to this day. He is pleased with it and it made me feel more comfortable.”

*

After talking to Marilyn for this article, I look at the paintings on my wall, on her web site, those in her famous calendars – great washes of colour surging like molten lava and tides thrashed by snowy winds – and smile at how a hobby painting has led to this second career. And, as an extra thought, that there is always time to find something new. You’ll never know how good you are until you’ve tried.

For more information see http://www.marilynperryart.com/

Prices range from $500 to £5,000 with commission prices separately. More studio tours are planned.

“Dark Flower,” encaustic, 2016.

(Too cute to pass on. Studio scene, 2004. Aaah,)

(Copy editors George Ashridge and Jane Bell)

To contact the editor responsible: mark.beech@dantemag.com