Spring Watch in Financial Markets: Stocks Climb – Towards a Cliff Edge?

March 26, 2017

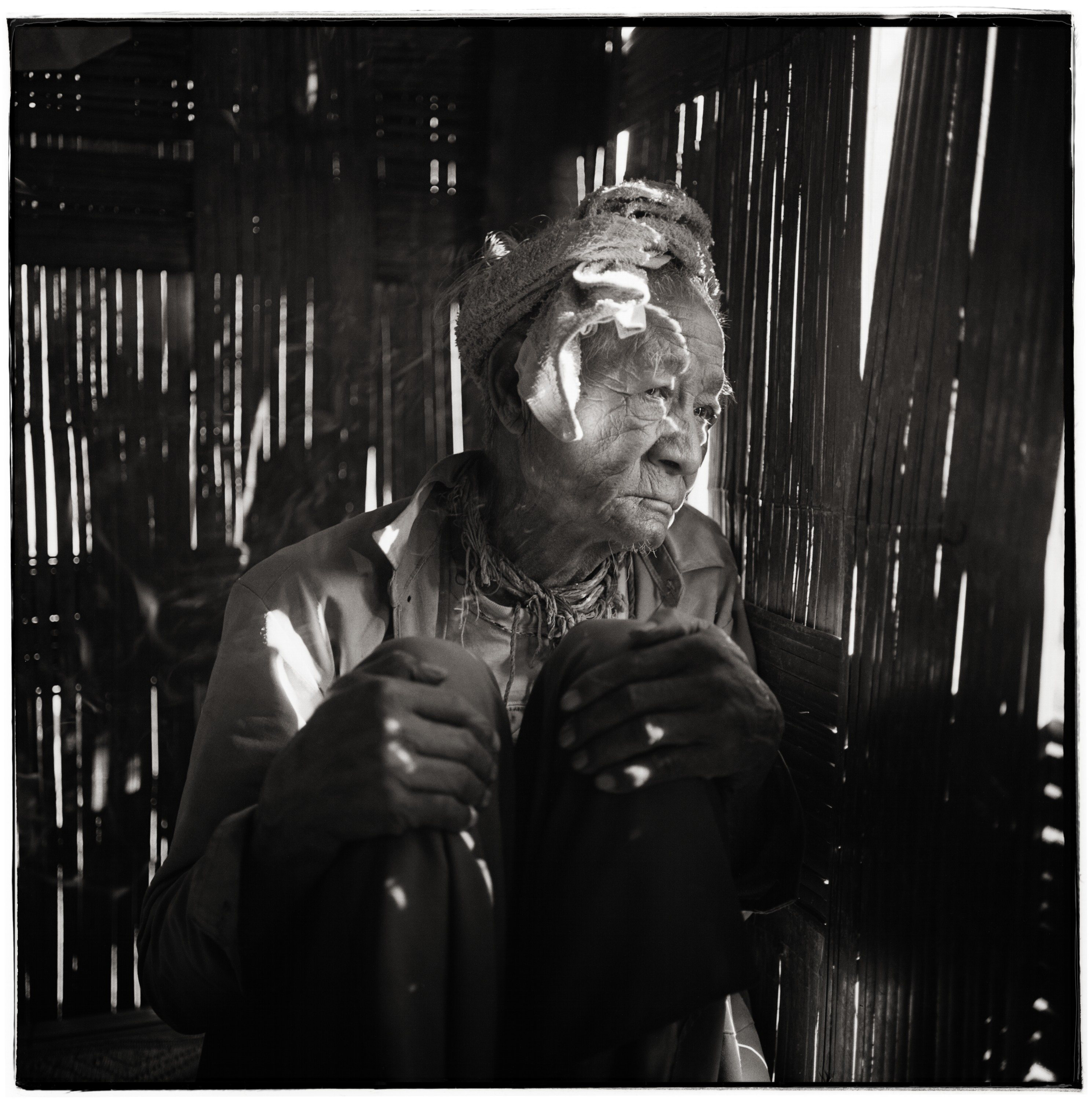

Living With Spirits: Thailand Caught on Camera

April 21, 2017Review by Nicholas Tufnell

Frankie is a twenty-something art school graduate whose small world is “coming apart by increments.” Working menial tasks in a Dublin art gallery and moving from box rooms to bedsits, she leaves behind the failures and disappointments of the city to live in her dead grandmother’s decrepit bungalow on ‘turbine hill’. Perched on the crest of a yawning valley and overshadowed by a solitary 200ft wind turbine, it is here that Frankie grieves for the loss of her grandmother and comes to terms with her own defeats and inadequacies.

Baume’s first novel, Spill Simmer Falter Wither, told a similar tale. Published in 2015 to largely favourable reviews, the story focused on the unremarkable life of an old man and his dog, capturing the poignancy of aging and loneliness. Baume revealed, unrelentingly, the tragedies of living on the fringes of society, of being invisible, unwanted and forgotten.

As with her debut, there is no significant plot to speak of in A Line Made by Walking, instead the thrust of the narrative is anchored around the character of Frankie. The novel begins and ends on death and this is a preoccupation for the protagonist throughout. It is a book steeped in loss. There is a pervasive sense of not simply an absence, but the more fragile and miasmic notion of the presence of an absence, both internal and external, physical and mental.

The glimmers of hope offered in the novel are quickly dashed down, usually through Frankie’s own unstable behaviour. Her family loves her; they are concerned for her and seek to help. The most devoted of all is her mother. Frankie idealises her at times: “My mother knows everything, I used to think all mothers did but in recent years I’ve come to realise it’s just mine.” At other times she treats mum with contempt: “My mother phones. ‘HAPPY BIRTHDAY LOVE!’ she shouts. ‘Oh fuck off, mum,’ I say. And hang up.”

The glimmers of hope offered in the novel are quickly dashed down, usually through Frankie’s own unstable behaviour. Her family loves her; they are concerned for her and seek to help. The most devoted of all is her mother. Frankie idealises her at times: “My mother knows everything, I used to think all mothers did but in recent years I’ve come to realise it’s just mine.” At other times she treats mum with contempt: “My mother phones. ‘HAPPY BIRTHDAY LOVE!’ she shouts. ‘Oh fuck off, mum,’ I say. And hang up.”

Frankie views the world with sadness and cynicism. She suffers from a form of mental illness, most likely clinical depression, which she refuses to treat with medicine or therapy. It is this illness that brings out some of the worst qualities in her, with behaviour that is at times not just unpleasant, but curiously vicious, such as the treatment of her mother on her birthday. Despite knowing Frankie is unwell, it is hard to excuse and sympathise with this more erratic behaviour. These moments emerge like short bursts of violence on the page and while they are intentionally out of character, they are nonetheless too distracting, too jarring.

This is a shame. Depressed people, even during erratic, emotional outbursts, are not inherently unlikable. So often quite the opposite is true – it is not difficult to sympathise with the depressed individual’s plight because many of us have experienced its horrors. Which is why it is such a disappointing and surprising failure of Baume’s to be unable to capture this, even fleetingly, during Frankie’s depressed-induced moments of rage and anger.

These small failures of Baume’s can be forgiven thanks to the strength of the rest of her writing. She writes with an old soul, revealing a wisdom and insight far beyond her years. She has the perception and light touch of a poet and the ability not just to write well when the time calls for it, but to maintain this, to be remarkably consistent and to be consistently remarkable. There’s an effortless profundity to Baume’s writing that never once draws attention to itself but rather quietly reminds you how terribly sad the world can be.

These small failures of Baume’s can be forgiven thanks to the strength of the rest of her writing. She writes with an old soul, revealing a wisdom and insight far beyond her years. She has the perception and light touch of a poet and the ability not just to write well when the time calls for it, but to maintain this, to be remarkably consistent and to be consistently remarkable. There’s an effortless profundity to Baume’s writing that never once draws attention to itself but rather quietly reminds you how terribly sad the world can be.

It is also nice to see Baume is unafraid to play more with the form of her writing this time around. A recurring device sees Frankie taking pictures of dead animals that cross her path while living in the green world retreat of turbine hill. These pictures, starting with a fallen robin, are part of a series intended to examine how, “…everything is being slowly killed.” Each chapter heading is named after the various dead creatures Frankie encounters, proving that not even the novel’s functional dividing lines can escape the central and apparently necessary base of decay.

These frequent and almost grotesque images of death and deterioration make for one of the great achievements of the book. So easily could this have become cliché, adolescent, banal. Instead, the subject is delicately handled with not just Frankie, but the now lifeless insects, animals and countryside, all becoming a greater metaphor for the inexorable but so often pointless striving for meaning, place and fulfilment.

Indeed, Baume’s writing on nature sees a bucolic idyll that has failed itself. It is ugly and flawed and yet it is precisely because of this flawed ugliness that beauty can nonetheless still be found, for this is the reality, this is the hard, unkempt truth of nature: you will die. You will become overgrown and forgotten and, like Joe, the obese and chronically arthritic golden retriever that belonged to Frankie’s grandmother, one day you will not wake up and your heart will stop, “like a soft pink clock that nobody remembered to wind.”

The deaths that surround Frankie, whether they are that of her grandmother or the flies beneath the kitchen window, present an enticing but very particular type of relief, of ultimate beauty, that can only be found in the quiescence of the inorganic world. She grasps for, but never quite reaches a life literally unlived, pushed back to an older state or driven forwards, towards a death that is neither violent or frightening, but rather a peaceful return to a place that can be called and felt to be home. “I want to go home, I want to go home, I want to go home,” chants Frankie. But she is wishing for a home that no longer exists, a home that disappeared with her childhood, along with her toddler leash and affectionate fistfuls of her mother’s pleated corduroy skirt.

Another recurring device sees the narrative punctuated with unusual asides in which the protagonist tests her artistic knowledge, for fear, she says, of forgetting. “Why must I test myself? Because no one else will. Not any more. Now that I am no longer a student of any kind, I must take responsibility for the furniture inside my head.” It is through her interpretation of these asides that we can gain a better understanding of Frankie’s mental state, a sort of narrative shortcut. For example, Frankie recalls Marco Evaristti’s Helena, an installation that consisted of live goldfish in food blenders, with visitors invited to turn them on or not. The director of the gallery was sued. “I search around online,” says Frankie, “I want to find out whether anyone pressed the button. Or whether everybody did.” Once again the emphasis lands on death and as before, Frankie is on the verge of – but not quite – willing it to happen.

The title of the book, of course, is not Baume’s – it has been appropriated, just as Frankie appropriated her grandmother’s bungalow. A Line Made by Walking is a photograph by Richard Long, an English sculptor and land artist. The picture, shot in black and white in 1967, is of a field in Wiltshire, with a large stretch of grass in the foreground and thick bushy trees in the distance. Discovered while hitchhiking from Bristol to London, Long began to walk up and down the undisturbed field until his movements had flattened the grass to form a long, straight, narrow line down the middle of the turf. This minimalist piece of early performance art is often thought to demonstrate Long’s early interest in movement, absence and the ephemeral.

The title of the book, of course, is not Baume’s – it has been appropriated, just as Frankie appropriated her grandmother’s bungalow. A Line Made by Walking is a photograph by Richard Long, an English sculptor and land artist. The picture, shot in black and white in 1967, is of a field in Wiltshire, with a large stretch of grass in the foreground and thick bushy trees in the distance. Discovered while hitchhiking from Bristol to London, Long began to walk up and down the undisturbed field until his movements had flattened the grass to form a long, straight, narrow line down the middle of the turf. This minimalist piece of early performance art is often thought to demonstrate Long’s early interest in movement, absence and the ephemeral.

And so then it becomes clear why Baume would chose this for her title, why she would wrap her book around this concept. Like Long, Frankie is interested in, perhaps even obsessed with impermanence. She is drawn to it, hoarding all that is temporary and fleeting as if they were rare and priceless gems. And like Long’s line in the turf, which is only visible when the light catches the tussled grass at the right angle, Frankie’s mark on the world is so delicate, so gentle, so easily missed.

Sara Baume by Thomas Langdon

“It’s time to postpone – if not entirely abandon – my burden of unrealistic ambition,” she laments, towards the end of the book. “It’s time to accept that I am average”. But ultimately, of course, she does not. She cannot quite accept that this is it, that this is truly everything. And so as the book ends, the ship she boards to nowhere draws out a new line, its wake temporarily carving and exposing a new path for Frankie to take, before being swallowed up by the sea.

While A Line Made by Walking is not as devastating or poignant as Baume’s debut, it makes up for this with a more inviting and fleshed-out world, a world of death, loss and impermanence, but also, depending on your interpretation, one of hope, beauty and kinship.

A Line Made by Walking by Sara Baume is published by William Heinemann, 320 pages, £12.99 hardback.