Capturing the Beauty of Movement: Meet Painter Marilyn Perry

April 21, 2017

Long Live the Book! Top Bookbinder Mark Cockram’s Art Offers Vision of Future

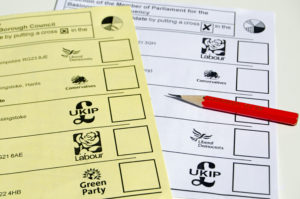

April 26, 2017In our spring issue of DANTE, we have talked about Arab Spring, and now it is the turn of Western Spring. This is being published online as France decides on a new president and all eyes are on Marine Le Pen. While she and others deny being fascists, the term is being used and right-wing extremism is returning.

This article was compiled before polls opened and after the the snap General Election called in the U.K.

Still, the current wave of far-right parties appealing to people’s fears is not an unstoppable tsunami, says Marc Forget.

((The views are those of the author alone and not necessarily endorsed by DANTE. The article appears in a slightly different form in the April-May issue of the magazine. Marc’s article follows.))

In recent years we’ve been witnessing a resurgence of isolationism, nationalism and fascism all around the world. The now far-reaching trend to divide into ever smaller “nations” and for nations to turn inward started slowly in the 1990s, with the breakup of the USSR and other countries in Eastern Europe, following half a century of increasing cooperation, continental alliances and regional unification around the world and especially in Europe. Today, one by one, the citizens of the global village are locking their doors, and telling their neighbours they will no longer help them.

Today’s common brand of nationalism has become as xenophobic, toxic and dangerous as that promoted by the Nazis in the 1930s. In countries where nationalists have recently won elections or referenda, hate crimes against minorities have increased dramatically, and anti-immigration, anti-foreigner, and anti-other sentiment is more prevalent now than it’s been a very long time.

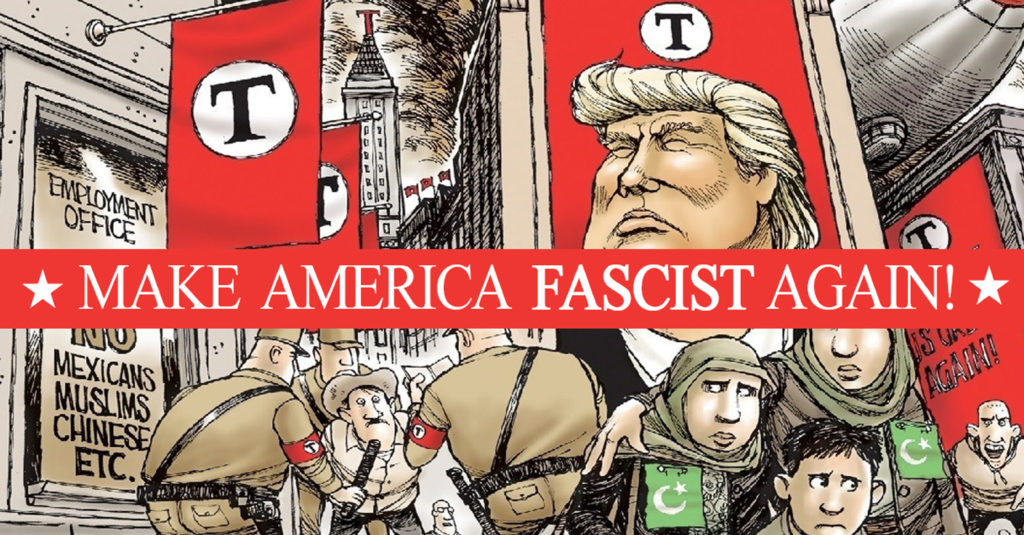

Twenty-first century fascism is upon us, and its proponents are found all around the world: Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, Norbert Hofer in Austria, Julius Malema in South Africa, Marine Le Pen in France, Nicol ás Maduro in Venezuela, Geert Wilders in the Netherlands, and, last but not least, Donald Trump in the U.S.A. As Brexit stoked the flames of nationalism, xenophobia, isolationism and other right-wing ideologies in Europe, ruling parties in many democracies elsewhere continued veering evermore to the right. Israel’s Likud party, the Liberals in Australia and Turkey’s AKP are but a few examples.

News media, including the liberal press, have contributed to the success of the right-wing demagogues by incessantly giving them exposure, covering even their most inconsequential ramblings and antics, perhaps for their entertainment value. There is something more insidious the press is also doing: using euphemisms to describe these political groups and their leaders. Those proposing authoritarian and nationalistic right-wing governments are no longer referred to as fascists but merely as populists, even though they represent the interests of ordinary people only in word and not in deed (Trump has already shown that his sympathies are with the billionaires who own the military industries, and not with the disenfranchised and underemployed who will lose their limited access to health care and have their children’s schools crumble in order to finance the huge increase in military expenditures; it also appears increasingly certain that Brexit will impose a heavy economic penalty on the average Briton). The press is also giving the innocuous label “alt-right” to even the most extremist reactionary groups such as the Ku Klux Klan and various other avowed white supremacist and neo-Nazi organizations.

Has this nasty trend gone far enough? Is it irreversible? Or is it perhaps a blessing in disguise that will trigger greater citizen engagement and activism, eventually resulting in more democratic and responsive governments, and moving us away from the perils of nationalism and fascism? There are many hopeful signs that a Democratic Spring may be taking shape, this time in the world’s most developed economies.

The defeat of Hofer’s FPÖ (Freedom Party of Austria) in Austria’s presidential election last December allowed liberals everywhere to end 2016 on a somewhat positive note. However, the way Hofer was defeated may be even more encouraging than the result of the election itself. Earlier in the year, as Hofer appeared set to win the presidential election, tens of thousands of ordinary Austrians mobilised into a broad coalition of civil society organizations whose members had one thing in common: they could not bear the thought of their country having the most extreme right-wing head of state since Adolf Hitler. The candidate who was backed by the Green party, Alexander Van der Bellen, won the presidency because the Greens organised with remarkable efficiency. Working with activist organisations, they created a decentralised grassroots campaign that wasn’t focused on its candidate but instead on values: respect, togetherness and tolerance. The campaign also highlighted Austria’s positive reputation internationally. Make no mistake, the race for the Austrian presidency was a close one, and the FPÖ is still highly popular; however, Hofer’s defeat showed that the current wave of far-right parties appealing to people’s fears is not an unstoppable tsunami.

In January 2017, Trump’s inauguration in Washington was immediately followed by the massive Women’s March, organised to protest Trump’s policies and attitudes. At an estimated 3.3 to 4.6 million participants, the Women’s March was the largest single-day demonstration in U.S. history. The event’s organisers are planning 10 other large public events in the first 100 days of Trump’s presidency.

In January 2017, Trump’s inauguration in Washington was immediately followed by the massive Women’s March, organised to protest Trump’s policies and attitudes. At an estimated 3.3 to 4.6 million participants, the Women’s March was the largest single-day demonstration in U.S. history. The event’s organisers are planning 10 other large public events in the first 100 days of Trump’s presidency.

Everywhere, organisations are springing up to counter the recent rise of fascist, nationalist and xenophobic ideology in mainstream politics. Many of these groups want more accountability and responsiveness from their elected officials. One of these organisations, DiEM25, states on its website: “For all their concerns with global competitiveness, migration and terrorism, only one prospect truly terrifies the Powers of Europe: Democracy!” These groups point to some viable political options between the calcified old centre and centre-left parties who can no longer claim to be progressive, and the new fascists appealing to a disenchanted and disenfranchised populace.

The movement against fascism isn’t just made up of small, scattered grassroots organisations, or a few fringe groups taking random actions; on 22nd May 2013, progressive leaders from around the world gathered in Leipzig, Germany, and founded Progressive Alliance (PA), a network of more than 130 socialist and social democratic parties and organizations. Participants in the network represent countries from Algeria to Zimbabwe, from every continent except Antarctica. PA espouses the values of democracy, justice, solidarity and gender equality, and seeks to collaborate with other progressive organisations, unions, think tanks, foundations and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in order to “make the 21st century a century of democratic, social and ecological progress.”

On 12-13th March 2017, Germany’s SPD (Social Democratic party) hosted a convention of Progressive Alliance in Berlin, which was entitled Shaping our Future. Its purpose was for “progressive parties worldwide working together more closely in times of new authoritarianism and growing populism.” The convention was attended by more than 100 people who included Austria’s Chancellor Christian Kern, Portuguese Prime Minister Antonio Costa, Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Lofven, and Italy’s Premier Paolo Gentiloni. Although most participants were European, some were also from the U.S. Democratic party, the Socialist Party of Uruguay, and India’s National Congress.

On 12-13th March 2017, Germany’s SPD (Social Democratic party) hosted a convention of Progressive Alliance in Berlin, which was entitled Shaping our Future. Its purpose was for “progressive parties worldwide working together more closely in times of new authoritarianism and growing populism.” The convention was attended by more than 100 people who included Austria’s Chancellor Christian Kern, Portuguese Prime Minister Antonio Costa, Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Lofven, and Italy’s Premier Paolo Gentiloni. Although most participants were European, some were also from the U.S. Democratic party, the Socialist Party of Uruguay, and India’s National Congress.

Media company Deutsche Welle reported that SPD’s leader Martin Schulz called for a new, fairer globalization. Schulz spoke of the current political climate as “a global counterrevolution against liberalism,” quoting British historian Timothy Garton Ash. Schulz defined this counterrevolution as a reaction to the inequalities resulting from years of unbridled financial markets, and to the blaming of immigrants and refugees for the worsening situation of the poor and middle classes. Schulz opened the convention with a call for the creation of a “new globalization” that would aim to produce social justice, and overcome poverty. The convention rejected isolationism and protectionism, stating these can never shield a nation from the global problems that are everyone’s responsibility.

Many analysts are suggesting that social democracy has found a new raison d’être, and is getting a fresh new wind in its sails with the widespread reaction against not only the current fascist, xenophobic and isolationist trends in mainstream politics, but also against the economic neoliberalism of the past 30 years.

Politics are still politics, however, and most participants in Progressive Alliance are political parties that seek power in their respective countries. Some of these parties may see this international alliance as little more than an opportunity to shore up support for their own agenda. So far, this network of politicians doesn’t seem to integrate grassroots organisations very well, and some of these civil society organisations may be reluctant to associate themselves with specific political parties, especially if they don’t share the same goals, other than fighting against fascism.

The challenge is now to mobilise these disparate groups, organisations and alliances to at least coordinate their work, if not collaborate, to help millions of voters everywhere see the rise of fascism for what it is (fascism, and not mere populism), realise they only stand to lose their freedom, civil and democratic rights by electing fascists, and defeat the extreme right-wing parties at election time. Austria gave us a very good example of how the concerted efforts of many groups can achieve success against the rise of fascism. There’s much work yet to be done, and uncertainties abound, especially in the upcoming elections in Europe, but there are many hopeful developments, and indications that democracy may be entering a new spring, a period of renewal and growth.

The challenge is now to mobilise these disparate groups, organisations and alliances to at least coordinate their work, if not collaborate, to help millions of voters everywhere see the rise of fascism for what it is (fascism, and not mere populism), realise they only stand to lose their freedom, civil and democratic rights by electing fascists, and defeat the extreme right-wing parties at election time. Austria gave us a very good example of how the concerted efforts of many groups can achieve success against the rise of fascism. There’s much work yet to be done, and uncertainties abound, especially in the upcoming elections in Europe, but there are many hopeful developments, and indications that democracy may be entering a new spring, a period of renewal and growth.

Marc Forget is a consultant in human rights, stakeholder engagement and education. He has worked for corporate, NGO and government clients in more than 45 countries.

Copy editor: George Ashridge. Editor responsible: Mark Beech