Dante recommends: Sara Baume’s consistently remarkable `A Line Made by Walking’

April 6, 2017

Capturing the Beauty of Movement: Meet Painter Marilyn Perry

April 21, 2017Living With Spirits: Thailand Caught on Camera

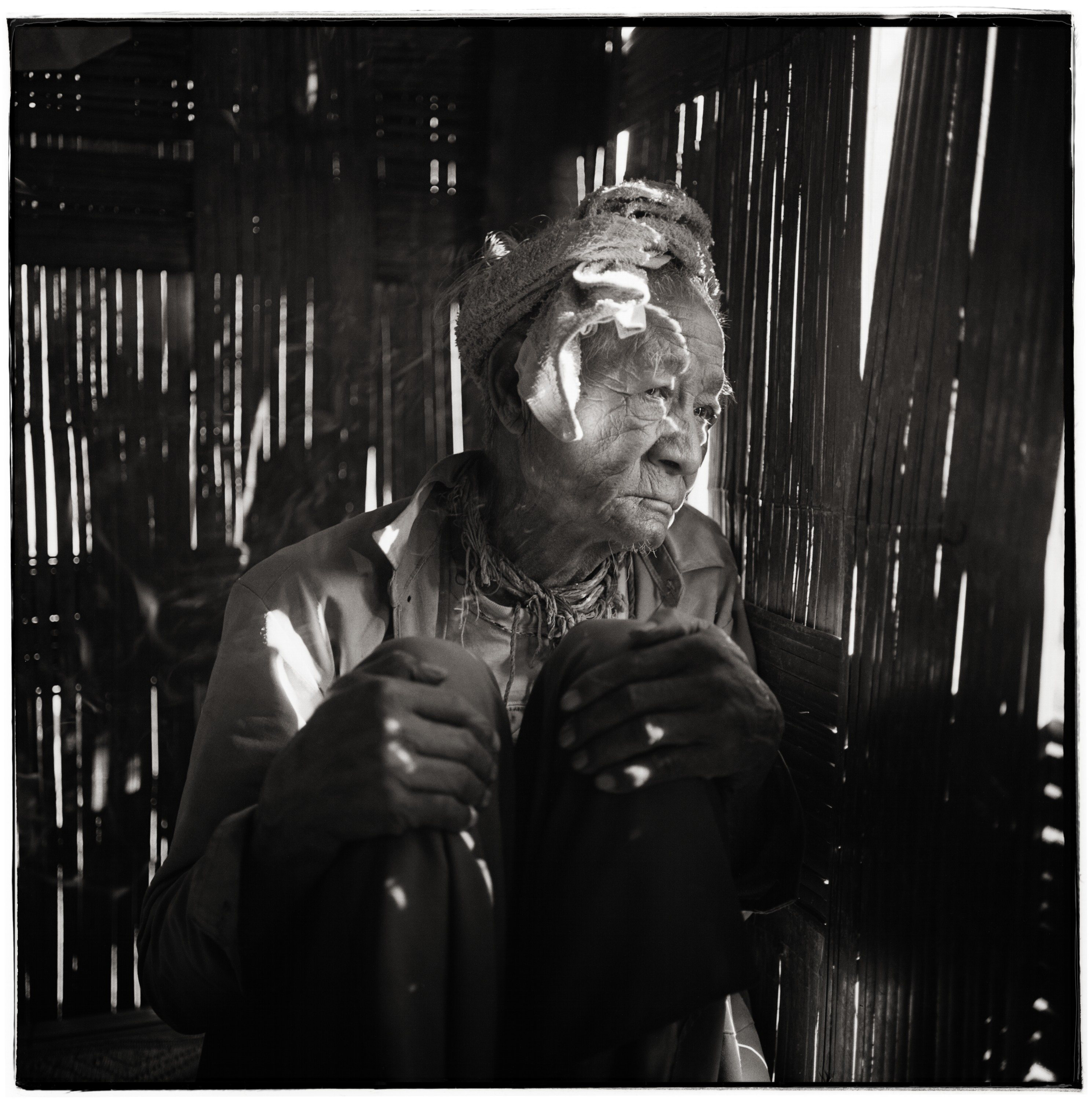

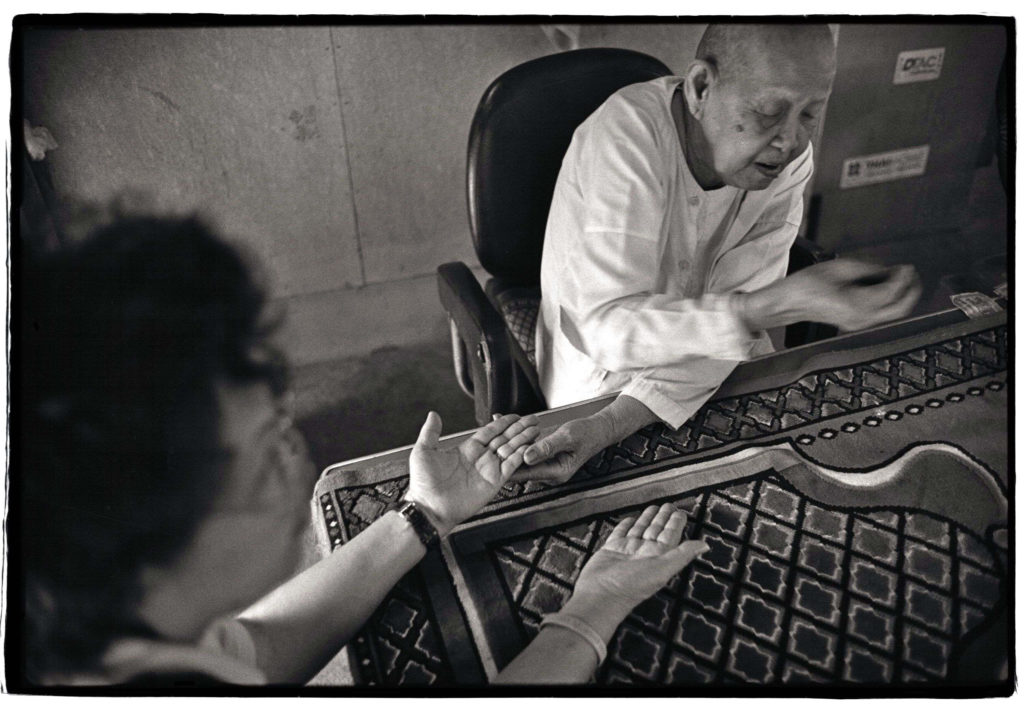

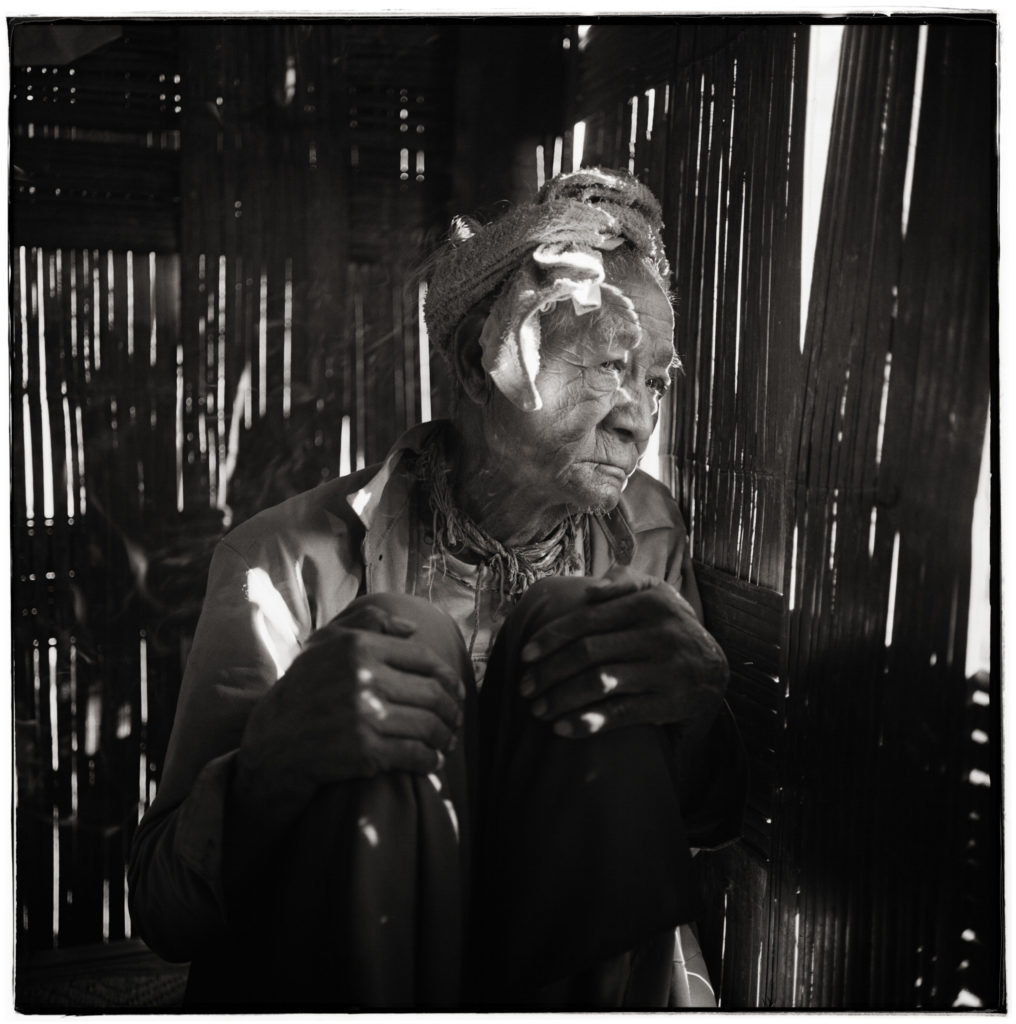

Thailand -Living with Spirits. 2006-2009. Lhoi Khai, a spirit doctor in Ban Nam Bo Sapei, Northern Thailand. Credit: Ben Davies/Asiaworksphotos.com Contact: sales@asiaworksphotos.com Legal Notice: Any use of this picture is subject to a license agreement entered into by the user and AsiaWorks Photography Ltd. All other rights reserved. Any re-use and redistribution of this image is prohibited. For sales enquiries regarding any additional use of this or other pictures from AsiaWorks Photography please contact sales@asiaworksphotos.com

Bangkok-based photographer and journalist Ben Davies writes about the multi-year project that took him from spirit doctors appeasing the spirits of the sky to entranced devotees and a floating nun which led to his book Living With Spirits.

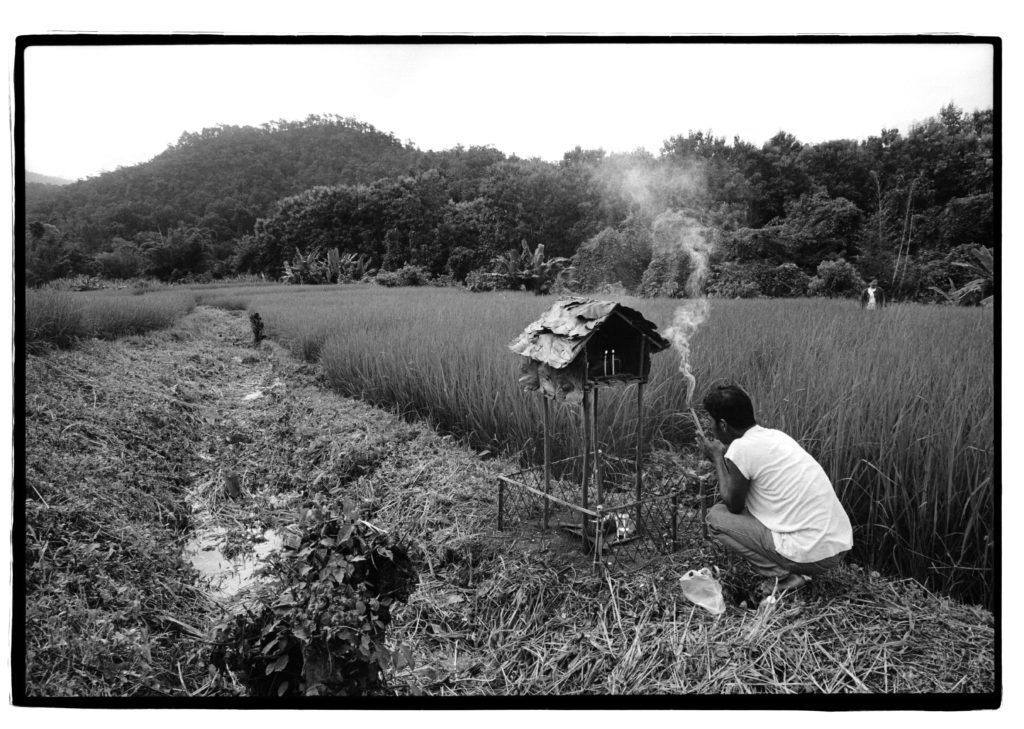

Nai Outhai, a Shan rice farmer, makes offerings to the spirits of the rice fields in the hope they will ensure a good crop. After the rice has been harvested and the husks removed, he will hold another ceremony to give thanks to the sun, the wind and the rain.

I grew up in East Sheen, a leafy suburb in southwest London, but for the past 25 years, Bangkok, Thailand’s sprawling, traffic-chocked and surprisingly charming capital has been my home. The place has an incredible energy about it, feeding my passion for photography, travel and culture. People say you can love the place or hate it but you can never be indifferent to it.

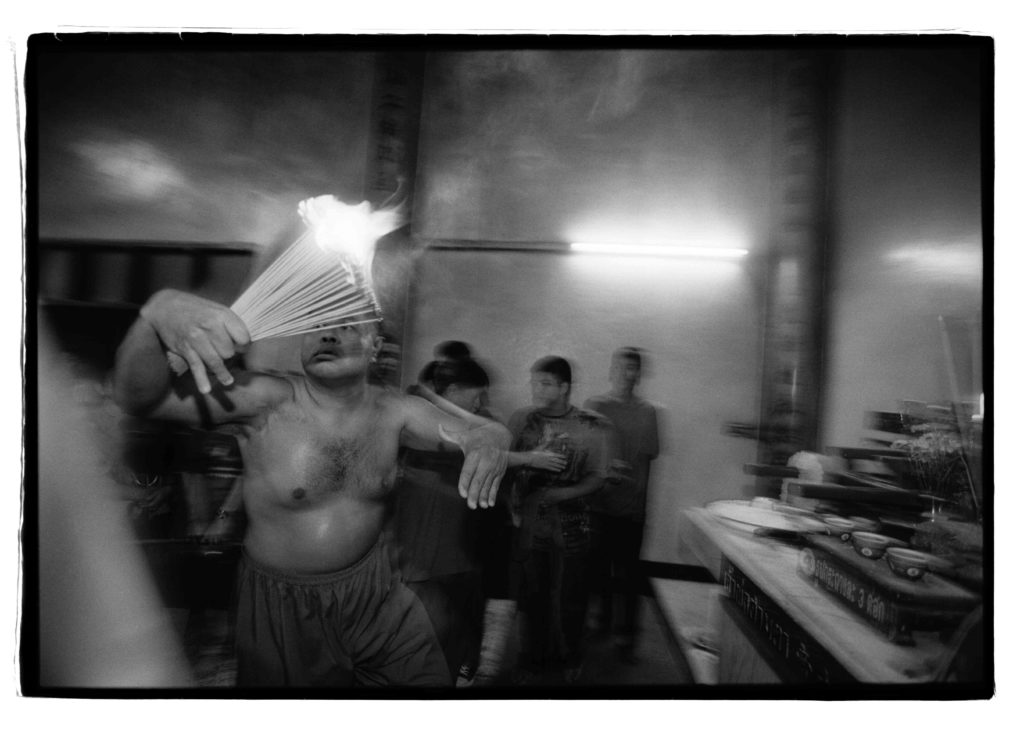

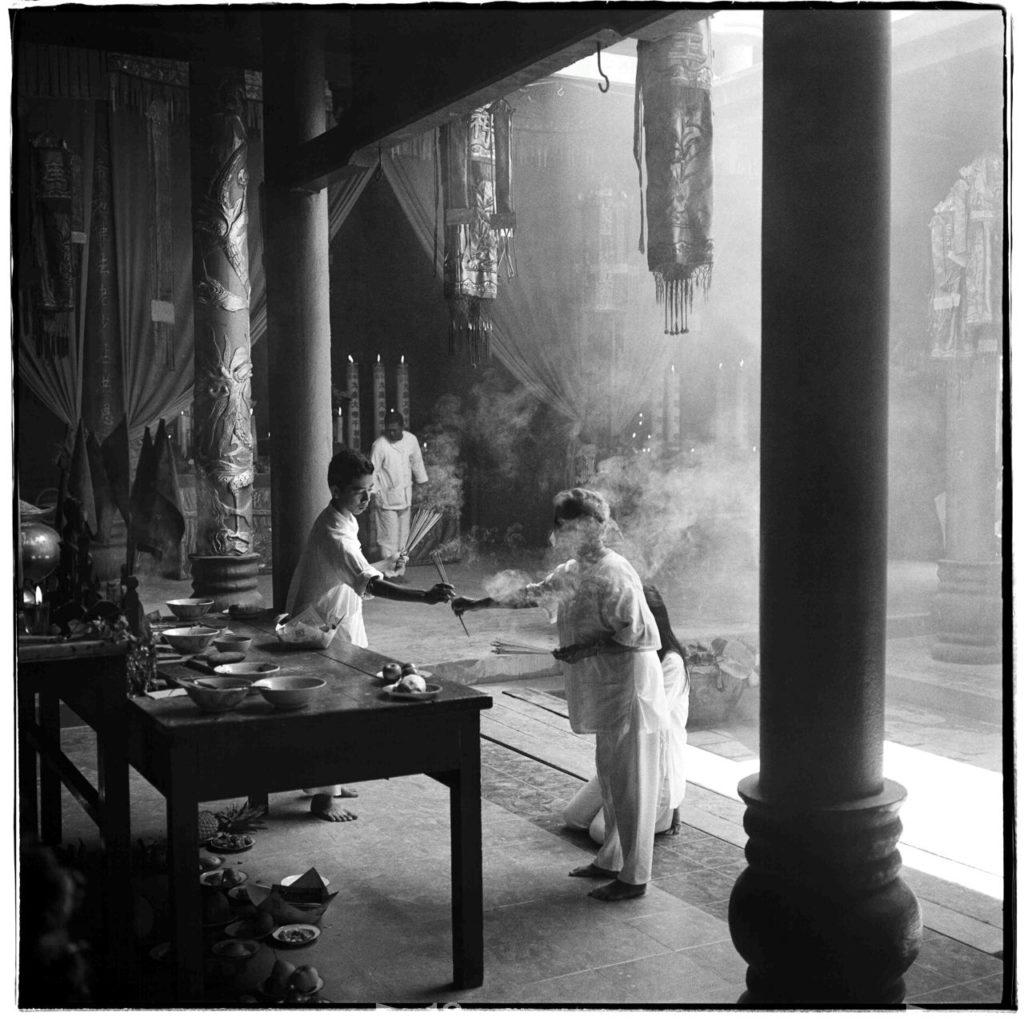

Five o’clock in the morning inside a Chinese shrine in Nakhon Sawan a man possessed by the spirits of his ancestors dances in front of an altar. After lighting incense sticks, he wrote down the words of the spirits on a piece of paper using his own blood.

Shortly after I arrived there in January 1989, I suffered a series of misfortunes that provided the inspiration for my latest project: my computer crashed, causing me to lose half of the book I was writing, I caught dengue fever, left my rucksack in a late night bar and fell down a manhole.

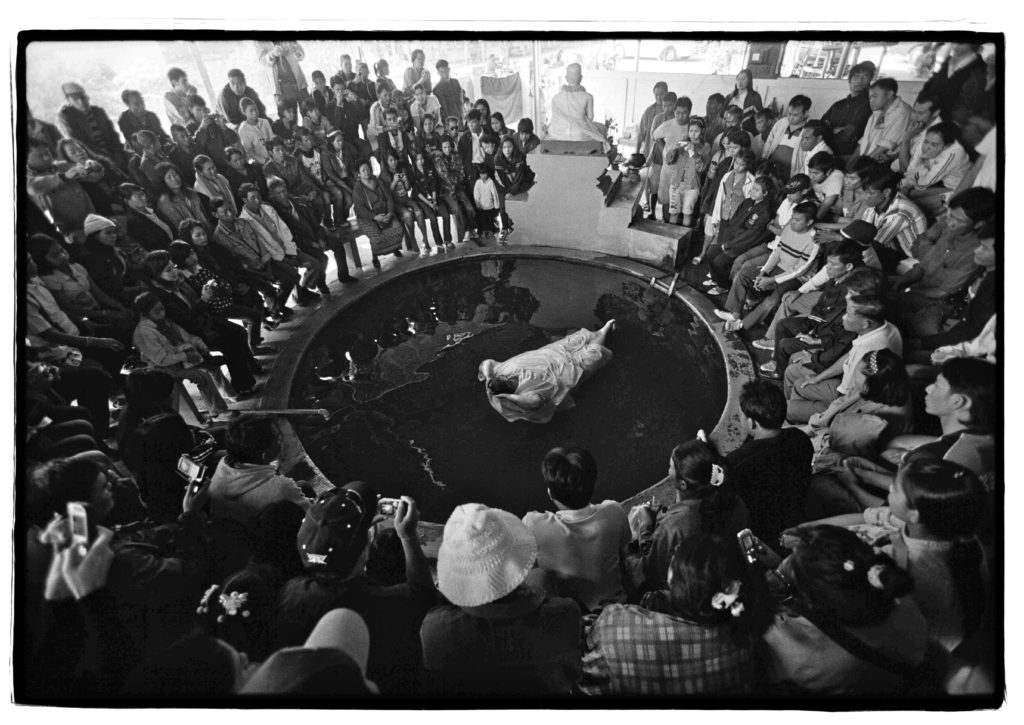

Maechee Siriwan, the famous floating nun, meditates in a pool of water in Kanchanaburi, Western Thailand.

My Thai friends were sympathetic. Had I offended a spirit, they asked, or worse still, had a curse placed on me? The only way to tell with any certainty was to seek forgiveness at one of the capital’s many spirit shrines.

At first I thought they were joking. But they were deadly serious. So a few days later, equipped with flowers, incense sticks and candles, I was taken to Lak Muang, one of the city’s best known shrines. As part of a ritual to make merit, I donated a pig’s head and two hard-boiled eggs to the guardian spirit. I sheepishly placed incense sticks and a candle together in my palms, pleaded for better fortune, clanged some bells to expel bad karma and released three caged birds. I returned home reinvigorated and, to my great surprise, at peace with myself. There was a whole new world out there which I knew next to nothing about.

A buddhist nun reads a devotee’s palm at the Nang Nak Shrine in Bangkok.

It was the start of a personal odyssey that in a sense has continued to this day. For weeks at a time, I would immerse myself in the realm of the spirits, travelling all over the country to witness bizarre rituals, exorcisms and religious ceremonies.

I photographed a blind astrologer, a floating nun and a monk who had spent ten years sleeping in a coffin to prove that he was not afraid of death. I watched men and women enter trances, writhing like snakes, roaring like tigers or occasionally somersaulting like monkeys. What I saw peeled back the layers of this ostensibly Buddhist society, revealing something far more diverse, fascinating and contradictory than the traditional narrative of this ancient kingdom would have us believe.

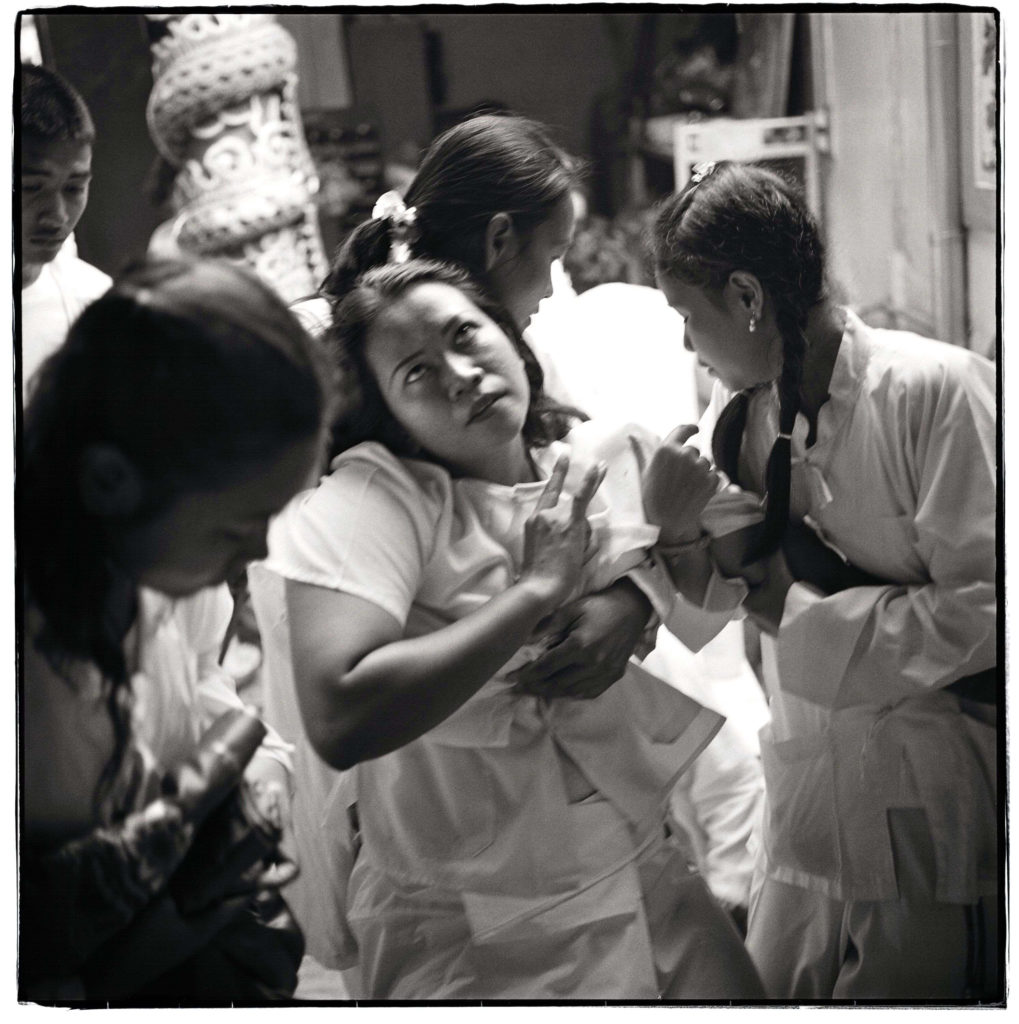

A young woman in a trance collapses in the Southern Province of Trang.

The first time I photographed a shaman making offerings of live chickens and rice whisky to the spirits of the sky, I remember wondering what on earth I was doing documenting weird animist rituals on the Thai-Burma border, far from civilisation.

After sacrificing the chickens, the old spirit doctor, his face wrinkled as a prune, inspected the blood seeping out of their gaping wounds. He paused for a moment before solemnly pronouncing that the spirits had been appeased and that all would be well in the months ahead. “This is a sign that the rains this year will be plentiful,” he said as the villagers looked on in silent reverence. Hours later, as we feasted on somtam, a spicy green papaya salad and khao niao, a type of glutinous rice, a torrential storm ensued, shaking the tin roofs of the village and blowing down the only satellite dish in town, but ensuring that the locals would have an abundant rice crop.

A chinese devotee in a trance in the Bang Neow shrine in Phuket, Southern Thailand.

How much of this was coincidence and how much did I believe? The spirits helped to make sense of these people’s lives. They provided comfort in times of hardship and hope when all else failed. My western scepticism may have remained. But then my survival does not depend on the rice crop and the monsoon rains.

My most shocking experience occurred on the popular tourist island of Phuket in southern Thailand where I was photographing the ‘vegetarian festival’. This annual purification rite is held by the local Chinese community to honour the gods, who centuries ago are said to have saved the community from a deadly plague.

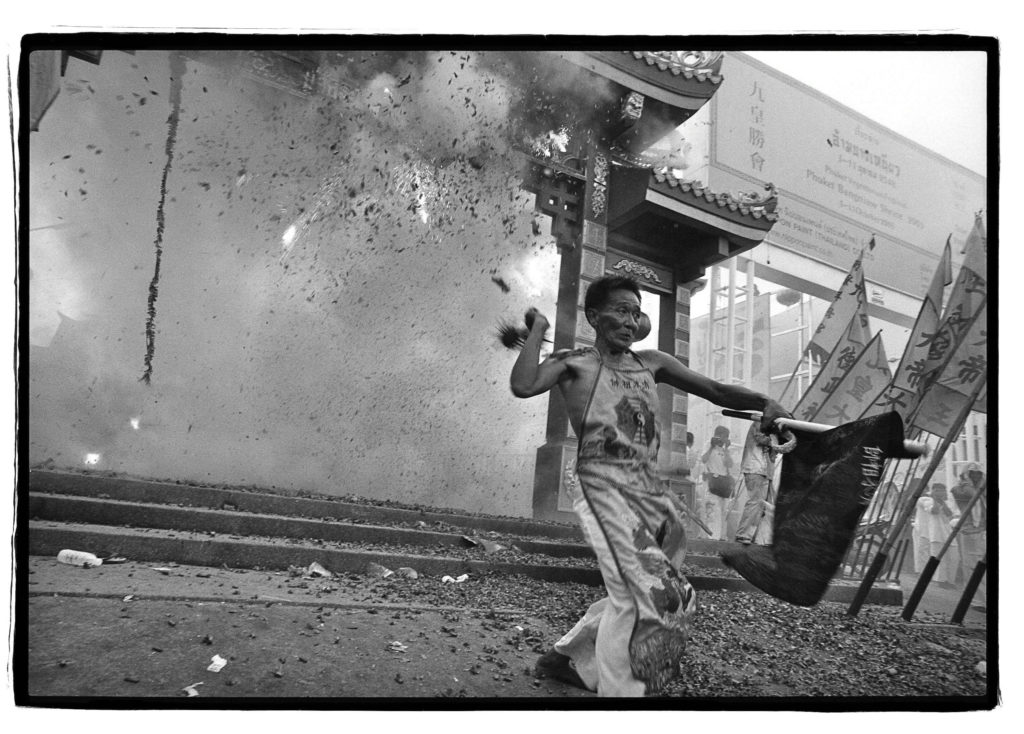

Waving flags and cracking whips, a procession of mediums charges through the gateway of Phuket’s Bang Neow Shrine. Their heads are covered with towels to protect them from exploding firecrackers. It is believed that the noise drives away evil spirits.

It was early morning. Out of a thick cloud of smoke, a line of grotesquely disfigured men staggered down the street towards me. They were dressed in striking blue, purple and yellow gowns. One man’s cheeks had been pierced by an axe and another by half-a-dozen carving knives that were still visible. In all, there may have been as many as 50 of them, each one accompanied by a helper who would pour cold water over their open wounds.

For close to three hours, these figures were led around the town, stopping occasionally to bless a family shrine or wish the inhabitants prosperity. As firecrackers exploded with a deafening roar meant to chase away the evil spirits, men, dressed in white, danced like madmen in the smoke. Then the crowds parted and the gruesome figures were gone, returning to a handful of shrines where they were coaxed out of their trance by having holy water sprinkled over their faces.

A vendor makes an offering in the guardian spirit house of Ban Khun Youn, Northern Thailand.

After it was all over, I spoke to one of the ma song or ‘tranced horses’ as they are known locally. He had a jagged scar down the left side of his face, which gave him the appearance of an ancient Chinese warrior. He told me that this ritual helped to cleanse the body and soul and could even save lives. “I became a ma song three years ago when my son nearly died from a fever,” he said. “I don’t remember having my face pierced but, after offering myself up to the gods, my son recovered.”

As a photographer and journalist, I have an enduring interest in disappearing cultures and traditions and the ways that people relate to them to give meaning and order to their own lives.

A man pays respect to Chinese deities in Trang, southern Thailand. During the ninth lunar month, the people celebrate ‘Ngan Kin Jeh’ or the ‘Vegetarian Festival’ by undergoing purification rites to cleanse their body and soul.

It seems to me that if anything, the allure of the spirits and the gods has increased in recent times, thanks to the dislocation of once close communities and the growing sense of alienation experienced by individuals across the world.

There is one story I especially like that I came across during my research into the spirits. A woman went to pray in the Erawan shrine, one of the most famous in Bangkok. She promised that if her wish to gain a husband was granted, she would cavort naked around the four-faced statue of Brahma, the Hindu god of creation. Her wish came true. So the caretakers arranged for a screen to be put around the shrine. The woman removed her clothing and danced nude in front of the statue in order to honour her pledge – after all, Brahma is supposed to love female beauty.

Clouds of smoke hover above a crowd of mediums who have gathered on Phuket’s Saphan Hin to show the power of the gods. Having entered a trance, these men and women walk over red-hot coals, bathe in scalding oil and perform other sacred rituals.

The first time I heard the story about the naked dancer and the Erawan shrine, I laughed out loud. But now I realise that such beliefs are too widespread to be dismissed out of hand.

Instead I try to hold back on my western preconceptions about superstitions which in many cases we still barely understand.

To honour the water spirits and wash away the sins and misfortunes of the previous year, a family launches a ‘krathong’ or float made from banana leaves on the Ping River in Chiang Mai. Each ‘krathong’ contains a lighted candle, three sticks of incense and a small offering of money for the water spirits.

And yet these beliefs and superstitions have far-reaching consequences. In many ways spirit worship discourages any real sense of responsibility. It allows people to blame their misfortunes on forces beyond their control. Thailand’s notoriously corrupt politicians have benefited from this attitude. Who cares if there is drought in the northeast or floods in the north, so long as locals blame the spirits?

But maybe I am being uncharitable. And in case it is all true, next time my computer crashes or I fall down a manhole or catch dengue fever, I will run to make an offering of a pig’s head and two boiled eggs at the Lak Muang Shrine.

Lisu villagers pray to the guardian spirit in Ban Nam Bor Sapei, Northern Thailand.

“Living With Spirits: A Journey Into the Heart of Thailand” is available on Amazon.com. See https://www.amazon.com/Living-Spirits-Journey-Heart-Thailand/dp/6167277028

More information: www.bendavies.asia

Thailand -Living with Spirits. 2006-2009. Lhoi Khai, a spirit doctor in Ban Nam Bo Sapei, Northern Thailand. ALL PHOTOS Credit: Ben Davies/Asiaworksphotos.com Contact: sales@asiaworksphotos.com Legal Notice: Any use of this picture is subject to a license agreement entered into by the user and AsiaWorks Photography Ltd. All other rights reserved. Any re-use and redistribution of this image is prohibited. For sales enquiries regarding any additional use of this or other pictures from AsiaWorks Photography please contact sales@asiaworksphotos.com