French Election Time and Democratic Spring: Of Fascism and Future Hopes Worldwide

April 23, 2017

A Flight of Imagination: Leee John’s Long-Term Plan

May 4, 2017By Mark Beech

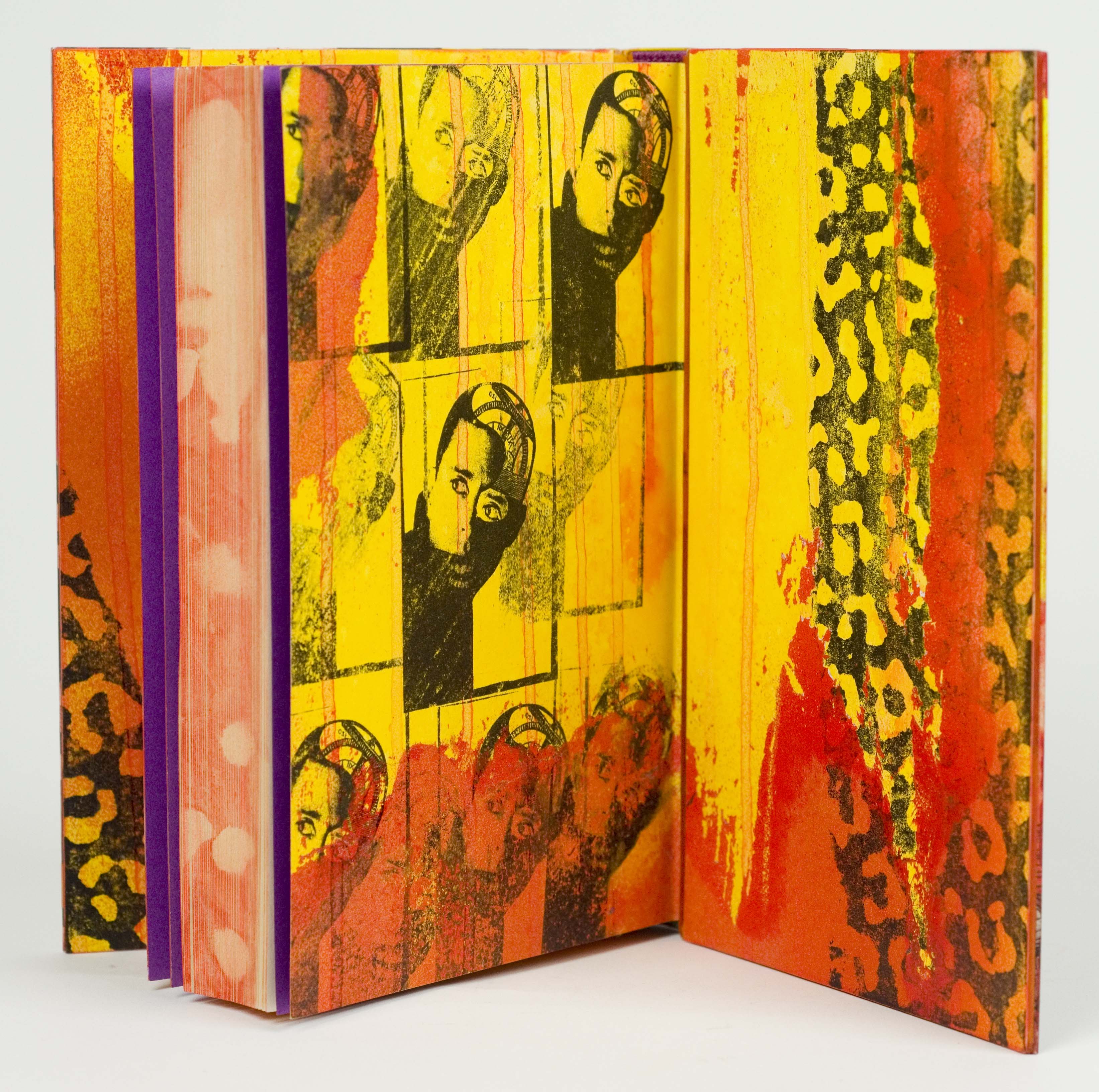

Is the book dead? Not if Mark Cockram has anything to do with it. DANTE’s editor meets up with this top bookbinder and discovers how his story and his creations mean that the book as a living artefact has its future very much secured

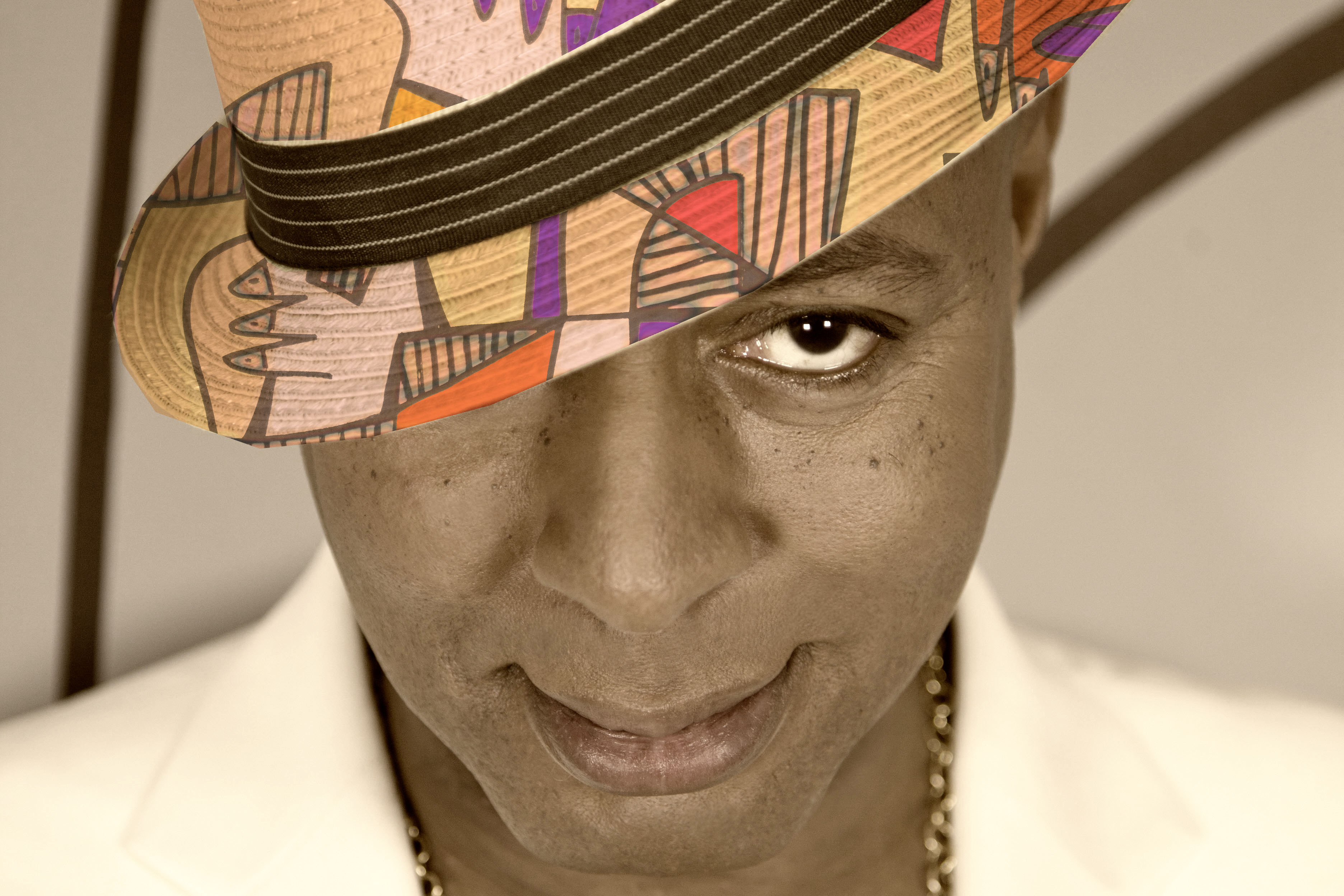

Mark Cockram in his studio, 2015 (Photo Mark Beech)

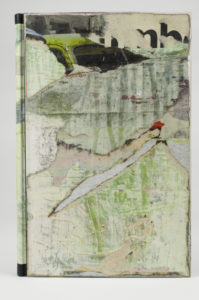

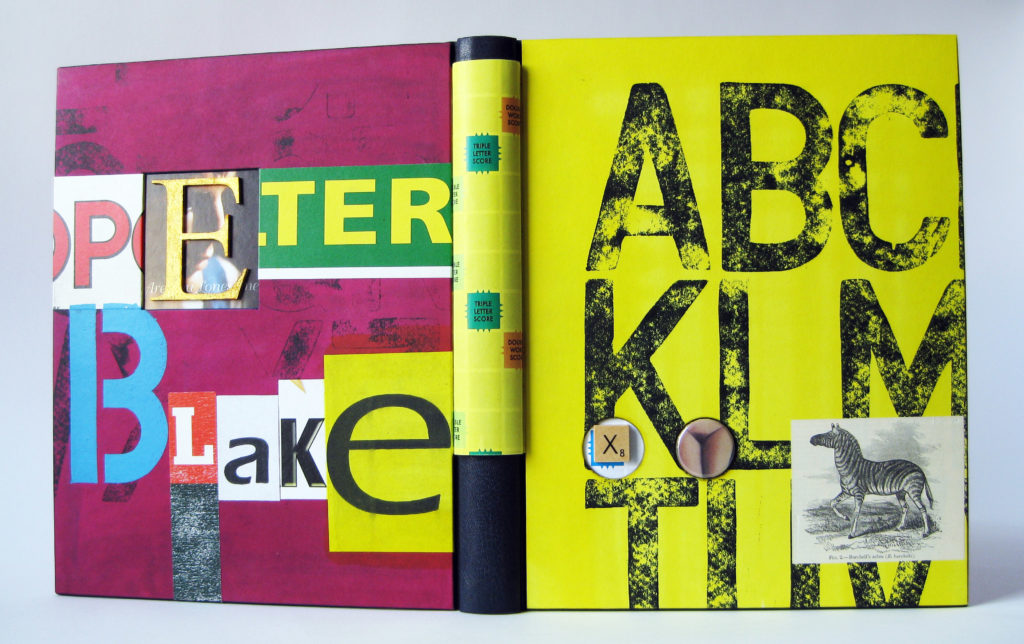

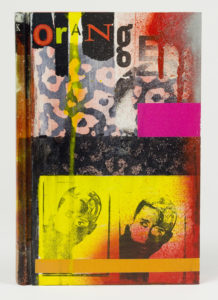

Sometimes wonderful works of art come from the most unlikely locations. The riverside area of Barnes, west London, has a villagey feel and many artistic residents. Hidden away though in a quiet courtyard is an unprepossessing studio run by Mark Cockram – a man known as one of the finest bookbinders. In this tiny one-man office, packed to the ceiling with his materials, he hand-crafts books that bear comparison to mediaeval illuminated manuscripts. Aside from leather, he uses unusual materials which include rat skin, snakeskin, sausage skin, gold leaf, fishbones, rattlesnake skins, fox’s brushes, eggs, metal and glass. These stunning books have also earned him a reputation is the bad boy of bookbinding – the man whose ideas challenge the conventional.

Cockram, an affable and articulate man, takes a break from an intricate binding to muse generally on the book.

“Nothing else quite matches a book: a three-dimensional articulated structure.” He picks one up, handles it, and sniffs the pages and ink. “Each has its own character, look, smell and tactile feeling. For the creative artist, it is a perfect medium to be able to have an intimate relationship with the viewer. As a means of communication, the book has an unprecedented history.” And he jests: “Of course it will survive. What do you do when your Kindle runs out of power?”

That Cockram should be involved in the world of books, on the face of it, is not surprising. His family has an antiquarian bookshop in Lincoln called the Harlequin Gallery: “We were always surrounded by books, dusty brown tomes, and I was always fascinated by the illustration and different styles of printing but I never thought about working with the book. I suppose it was a case of not seeing the trees for the wood, or vice versa.”

That Cockram should be involved in the world of books, on the face of it, is not surprising. His family has an antiquarian bookshop in Lincoln called the Harlequin Gallery: “We were always surrounded by books, dusty brown tomes, and I was always fascinated by the illustration and different styles of printing but I never thought about working with the book. I suppose it was a case of not seeing the trees for the wood, or vice versa.”

But there is an irony here: “When I was at school, dyslexia was not recognised. One was called either ‘lazy’ or ‘stupid’, and it was only after I started at art college that it became apparent that I was mildly dyslexic. When I was at school, I found books extraordinarily difficult to read. I was in and out of remedial classes because my written and reading English was so poor.” Now he is printing, working with top authors and publishers: “It is strange how life turns around sometimes.”

His home was in the rural county famous for the Lincolnshire poacher, and Cockram confesses that he got in at the local college of art and design by bribing the vice principal with a brace of pheasants. “It was common currency then and a very good two years’ grounding for me. From there, I ended up working in Paris and that’s where it all started. It sounds very glamorous working in Paris, but basically I was installing art-deco toilets into a refurbished apartment block and that’s not so good.”

This was the late 1980s. Then came an epiphany.

“I was walking home to my digs on a wet Wednesday evening and I saw a public building was open and I nipped into it just to get out of the rain. My French is appalling, it was even worse then, and I managed to get in via the exit and it turned out to be a an exhibition from the collection of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris and it featured books of hours and beautiful illustrations, all the way up to the works of Gilbert & George. I did the exhibition from back to front, going against the tide of people, with a lot of Gallic shrugs, saying ‘you’re doing it wrong.’ I eventually got to the beginning of the exhibition and I found that it made sense. So I did it again, this time walking the correct way through. I was hooked and realised that I loved books. So I finished my contract, moved back to the U.K. and started studying.”

“I was walking home to my digs on a wet Wednesday evening and I saw a public building was open and I nipped into it just to get out of the rain. My French is appalling, it was even worse then, and I managed to get in via the exit and it turned out to be a an exhibition from the collection of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris and it featured books of hours and beautiful illustrations, all the way up to the works of Gilbert & George. I did the exhibition from back to front, going against the tide of people, with a lot of Gallic shrugs, saying ‘you’re doing it wrong.’ I eventually got to the beginning of the exhibition and I found that it made sense. So I did it again, this time walking the correct way through. I was hooked and realised that I loved books. So I finished my contract, moved back to the U.K. and started studying.”

First he did a bookbinding and conservation course, moving on Guildford College – “it was another magic time” – graduating in 1992. He has never kept count of the number of books that he has worked on, but says that it is clearly thousands, if not tens of thousands, especially given the work that he does with students, who may be making a number of projects at any one time. Cockram reckons he has done fewer of the design bindings – “the masterpieces if you like” that can take months just for a single volume, with experiments and working with new materials.

First he did a bookbinding and conservation course, moving on Guildford College – “it was another magic time” – graduating in 1992. He has never kept count of the number of books that he has worked on, but says that it is clearly thousands, if not tens of thousands, especially given the work that he does with students, who may be making a number of projects at any one time. Cockram reckons he has done fewer of the design bindings – “the masterpieces if you like” that can take months just for a single volume, with experiments and working with new materials.

One project grew out of a question from his friend and neighbour, the poet Roger McGough. “Basically, Roger had asked, ‘how big can you make a book?’ and I pointed to a door and said ‘that big,’ and it started from there.” They had an installation for the Museum of Liverpool making books out of reclaimed front doors and they went on to do it at the Dubai Literary Festival – this time working with local artists who had very different ideas on the same thing. “We realised we had the book in common, it is a universal language.”

Another of his eye-catching works is in homage to Joseph Cornell, one of Cockram’s favourites, a U.S. artist who is known for his collages boxes of related objects. “One of the materials he used was sand. I wanted sand on the book cover but I wanted the sand to move, form different shapes and cascade over forms, so every time you picked the book, it would be a new binding. It would be forever new, forever fresh.” A few of his books have been auctioned at Bonhams and he is watching developments with interest.

Another of his eye-catching works is in homage to Joseph Cornell, one of Cockram’s favourites, a U.S. artist who is known for his collages boxes of related objects. “One of the materials he used was sand. I wanted sand on the book cover but I wanted the sand to move, form different shapes and cascade over forms, so every time you picked the book, it would be a new binding. It would be forever new, forever fresh.” A few of his books have been auctioned at Bonhams and he is watching developments with interest.

Each book is different with an average price of perhaps £150 for a relatively simple but beautifully handmade while some of the most complex works can cost very considerably more with delicate crafting of 23.5 carat gold and leathers which can be more expensive than gold leaf.

He also has a role in helping with Britain’s premier literary prize the Man Booker. As one of fewer than 30 Fellows of Designer Bookbinders since 2001, he has been invited to bind some of the shortlisted works. Each must be done in four weeks, with a presentation copy and box. One he bound was Peter Carey’s Paris and Olivier in America. The author, who was then hoping for a third Booker, loved the binding and asked Cockram how many Bookers who had been at. When Cockram told him about eight times, Carey’s reply was “very Australian, very short,” he says. (One has not really lived until one has been f—offed by Carey.) “It was all very polite, very tongue in cheek and he took it well, a nice chap.”

He also has a role in helping with Britain’s premier literary prize the Man Booker. As one of fewer than 30 Fellows of Designer Bookbinders since 2001, he has been invited to bind some of the shortlisted works. Each must be done in four weeks, with a presentation copy and box. One he bound was Peter Carey’s Paris and Olivier in America. The author, who was then hoping for a third Booker, loved the binding and asked Cockram how many Bookers who had been at. When Cockram told him about eight times, Carey’s reply was “very Australian, very short,” he says. (One has not really lived until one has been f—offed by Carey.) “It was all very polite, very tongue in cheek and he took it well, a nice chap.”

Carey’s written words will certainly endure, as will Cockram’s bindings, in private collections and on public display – not simply as museum pieces (they are already in the British Library and Victoria & Albert Museum) but as living books. “It is the beauty of working with the book, it is the language used and one can use one’s imagination, not everything is set out for you. When they say ‘the sky is blue,’ it is your interpretation of what the blue is.”

For more information, http://studio5bookbindingandarts.blogspot.com/ or http://www.abbyschoolman.com/.

This article first appeared in a slightly different form in the print edition of DANTE in April-May 2016 and on our phone app:

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.jellyfishconnect.dantemagazine

https://itunes.apple.com/gb/app/dante-magazine/id1096581967?mt=8