Making American Cities Great Again! American Architecture After the U.S. Withdrawal From the 2016 Paris Accords

August 13, 2017

The Competing Narratives of Brexit: Delay, Recession and Confusion

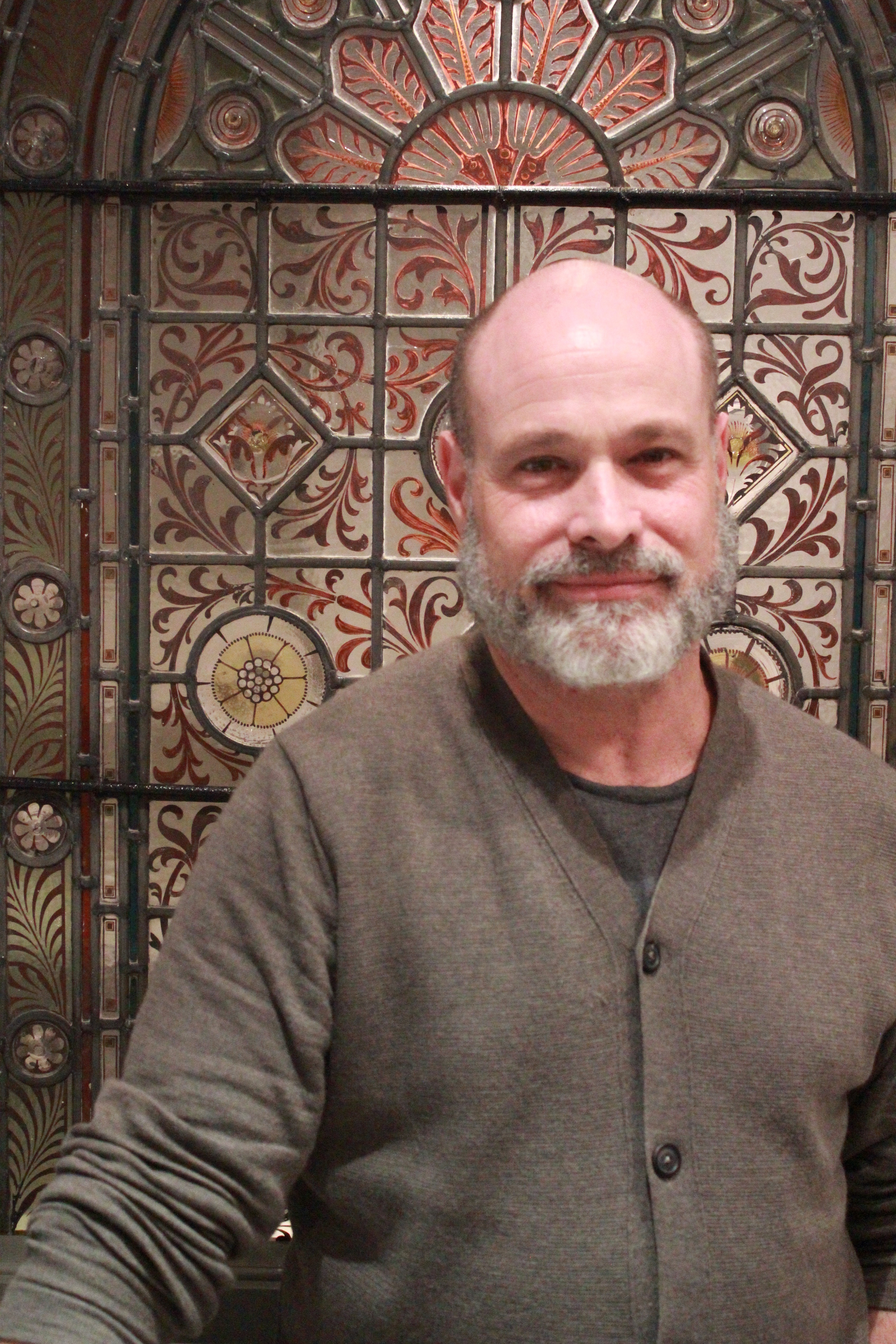

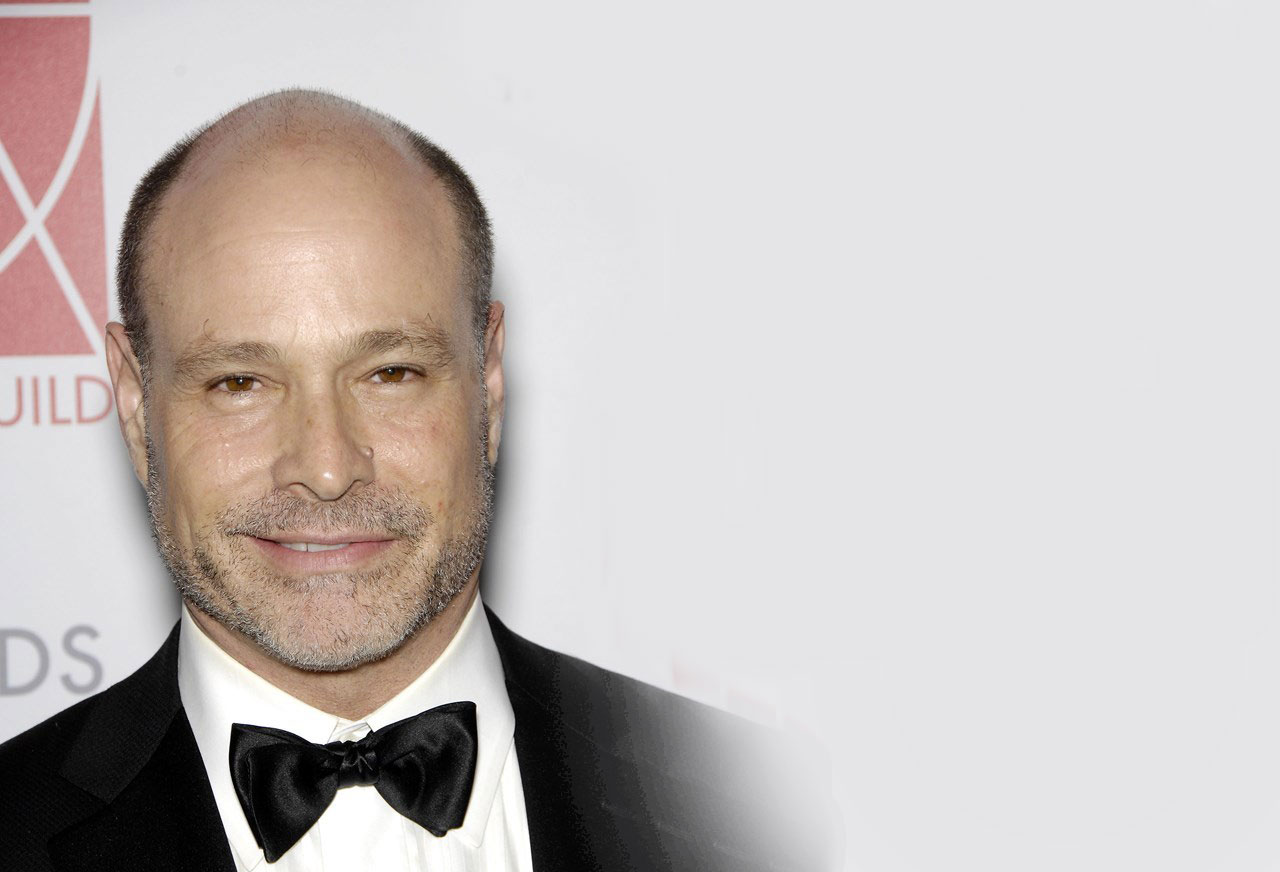

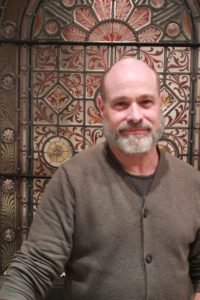

September 4, 2017 Jon Hutman has been responsible for the look of many Hollywood movies. DANTE’s Massimo Gava catches up with him to find out about the role of a production designer.

Jon Hutman has been responsible for the look of many Hollywood movies. DANTE’s Massimo Gava catches up with him to find out about the role of a production designer.

Jon Hutman

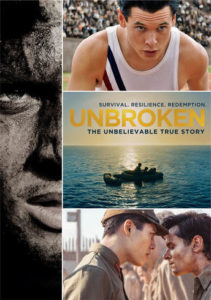

What can we say about Jon Hutman without going into details of a man that has helped to created most of the best-known films made in the last 20 years? A list would include: The Mummy, Unbroken, The Tourist, It’s Complicated, The Holiday, The Interpreter, Something’s Gotta Give, Quiz Show, A River Runs Through It, and Heathers.

A fuller list is on IMDB if you really need more. But clearly the filmography of this man shows that he has been at the top of the movie industry. At the time of the interview he had just finished The Mummy with Tom Cruise, which was released in June.

So, Jon, explain to the wider audience what the role of a production designer is in a movie.

A production designer is a title that was created for William Cameron Menzies, the designer of Gone With the Wind. It means the guy that is not only responsible for the set design but for overseeing the look of the whole world of the film, including cinematography, costumes, visual effects, make up and so on. Each has a person responsible for that department, but it all comes under the role of the production designer to coordinate that.

And how do you coordinate all of that?

For me, the process begins with the script and the story in it. The difference between set design and architecture or interior decoration is when you design for a movie or a TV show, there is a need to tell the story of the person that lives in that story. It is not just who lives in that house but also what happens in that house. Are they rich or poor, neat tidy or messy, are they in London or Italy or wherever? And yet it will depend on the setting if it is a romantic comedy or a horror film. These are all things that a production designer has to take into account to help the director realise his vision.

For me, the process begins with the script and the story in it. The difference between set design and architecture or interior decoration is when you design for a movie or a TV show, there is a need to tell the story of the person that lives in that story. It is not just who lives in that house but also what happens in that house. Are they rich or poor, neat tidy or messy, are they in London or Italy or wherever? And yet it will depend on the setting if it is a romantic comedy or a horror film. These are all things that a production designer has to take into account to help the director realise his vision.

Is it difficult to grasp the vision wanted?

It is my responsibility to figure out what the director wants. Different directors bring different sets of skills and expectations. I worked with several directors whose background and experience has been primarily as an actor, and others whose background has been writing screenplays.

To give you an example, years ago I worked with Adrian Lyne (9 ½ Weeks and Fatal Attraction) on the remake of Lolita with Jeremy Irons. Adrian comes from a commercial background and is extremely visual. It was my responsibility to help him translate his ideas into practical solutions. I also work with Nancy Meyers; she’s a writer who creates stories that are very personal. Her films tend to focus on strong career women (who live in beautiful houses!) Like Something’s Gotta Give (with Jack Nicholson and Diane Keaton) or The Holiday. She will have ideas and those ideas will help me to get inside of her head and understand the world that she is imagining and help her to create that.

Publicity stills photography on the set of NBC Universal’s Movie ‘Unbroken’

And did you manage to get inside the head of Angelina Jolie as well?

Johnny Depp as “Frank” and Angelina Jolie as in Columbia PIctures’ THE TOURIST.

Well, I have worked with Angelina three times now. We met on The Tourist, shot in Venice with Johnny Depp. After that, she asked me to do In the Land of Blood and Honey, a love story set with the backdrop of the Bosnian war. Then we did Unbroken, a World War II true story about an Italian-American Olympic athlete Louis Zamperini. His family originally came from Verona, Italy, but he was born in New York. He was an Olympic runner, then became a navigator, His plane crashed in the Pacific Ocean and he survived at sea for 47 days. Then he was captured by the Japanese and survived in a Japanese prison camp until the end of the war.

I have also worked on several films with Jodie Foster, who is a friend of mine from college [Yale]. We did Little Man Tate, the first movie she directed, and then Nell.. Then I did three films with Robert Redford—another accomplished and inspiring actor and director.

Although each of these collaborations was different, they shared an evolutionary approach, which I believe comes from the actors’ process. For example, when I work with Angie, she is not like, “Here is the script, now go and design the set.” The whole film evolves – story, script, actors, locations, and design. When we did Blood and Honey, I did not know much about the Bosnian war, even though it happened in recent history. Another director I am friendly with, Phil Robinson, had been very involved with the Bosnian situation and had written a film he intended to shoot in Sarajevo after the war. He was extremely generous with both Angie and I in terms of sharing his experiences and contacts in the country. And although we ended up shooting our film in Budapest, the understanding of the conflict we got from Phil helped us to replicate that sense of place in Budapest.

When you scout for locations do you look for what goes through your mind?

Each film is different and, increasingly in the last five years or so, the choice of the location is very much dictated by tax incentives which are now available all over the world. Now we are sitting here in London, where I spent the last year doing The Mummy because of the strong tax incentives that are here in the U.K. There are some incentives in Canada and Hungary, which is why we did Blood Honey there, but you try to find the right place that gives that element.

Hungary turns out to be an excellent double for Sarajevo – that eastern-European image with communist flavours shared by the recent history of the two countries was perfect for us. Unbroken was a crazy story that was initially supposed to be made in Hawaii and North Carolina but this was cost prohibitive. Then we had the idea of doing it in Australia. That was more suitable to the production logistics because we had to begin shootin with the final scene when guys were emaciated—the concentration camp and the raft. Then we gave them time to regain their weights to shoot the first part of the movie. Also, weather wise, Australia is the opposite season for us and we needed a lot of outdoor work for our scene in the water and the Australian studio was perfect for that.

Hungary turns out to be an excellent double for Sarajevo – that eastern-European image with communist flavours shared by the recent history of the two countries was perfect for us. Unbroken was a crazy story that was initially supposed to be made in Hawaii and North Carolina but this was cost prohibitive. Then we had the idea of doing it in Australia. That was more suitable to the production logistics because we had to begin shootin with the final scene when guys were emaciated—the concentration camp and the raft. Then we gave them time to regain their weights to shoot the first part of the movie. Also, weather wise, Australia is the opposite season for us and we needed a lot of outdoor work for our scene in the water and the Australian studio was perfect for that.

When we did By the Sea, set in the south of France, we had a window from September to November but we wanted to be in a place that can be warm enough with sun so that we can do sunbathing and not be freezing cold. So the weather (plus the tax incentives) drove us to Malta.

And how do you work with product placements, as seen a lot in these movies?

It depends. In the old days, it used to be that someone gave us a free computer to use and we put it on screen, sort of tit-for-tat. Now there tend to be long-standing agreements between the studios and other large corporations.

If you need to give some advice to somebody that wants to get in the same position you are in now what will you recommend?

Run the other way! Next question…

“Something Gotta Give” beach house design

Oh, come on, tell us…

I can tell you how I got in. I grew up loving and doing theatre and in the process I became less an on-stage guy and more behind the scenes and became more interested in designing the set. My university had a scenic design programme, headed by Ming Cho Lee, who was an idol for me when I was a student. I got into film mainly because I thought I could make a better living out of that, a sort of mercenary thing.

There are now set-design programmes in many schools, but production design is really a craft. Any school will give that knowledge but then with the system there is a kind of block hierarchy that you start in a lower role and move up to be a production set designer. I started at 25 as a set designer when I did my first movie. What I could say to the people who are starting now is that increasingly the job is done digitally and there are more opportunities as digital effects and less conventionally-designed scenery.

Robert Redford

And what would you say to an actor?

I found the process of becoming an actor very challenging. That’s maybe why I made that choice to stay behind the camera. It’s one thing when you do it at college with your friends. It’s another thing having that constant challenge for the ego, because I think it is very difficult to separate yourself from the work. I can accept the fact that somebody does not like the set design or the experience I have for that particular movie, but if somebody rejects me as an actor, it feels like they’re rejecting me.

Everybody in the world wants to be in the movie business. It is oversubscribed beyond belief and yet there are always people looking for the next big thing. You cannot do it because you want to be famous, can’t do it because you want to be a star, you can’t do it because you want to be rich. You have to do it because you love what you are doing and in my experience if you can find that fire within yourself, it will happen.

Jodie Foster

What is next in the pipeline for you then?

A flight back to Los Angeles tomorrow and a little break. That is completely normal in this business.

It is hard to believe you will stay put for long, considering that you are a hyper creative man and in constant demand for new projects but if you say so, Jon. Thanks for being with us.

Angelia Jolie