Italy. An annihilated country goes to polls.

March 2, 2018

Why Issues Matter More Than Leaders

March 16, 2018Together with the prince of Allegria, Roberto Benigni, we remind the Italian politicians about to form a new governement the true meaning of their national anthem. Massimo Gava writes.

In the San Remo festival in 2011 , Roberto Benigni, winner of a double Oscar back in 1999, succeeded in capturing the attention of 15 million Italians to a topic that no Italian politician has ever managed to cover since World War II: the meaning of their national anthem. After the results of the general election on the 4th of March 2018, we want to remind Italian politicians of the true meaning of their national anthem.

Italy is one of the world’s economic leaders. Like many other developed countries in recent years, it has had to face the challenges of an economic downturn.

One might say that Italians get patriotic only when they win the World Cup, but given the recent results, even that source of pride has gone.

For a couple of months, before the recent election, I’ve been receiving clips of the Roberto Benigni video from various friends around the world. Silently I responded with: “Yes, we know the actor is funny. So what?” Then the teenage son of a friend of mine quoted a phrase I recognised from the Italian national anthem: “United, for God’s sake! Who can defeat us?” Knowing that the boy is more inclined to quote rap crap rather than history teachings, my reluctance towards Benigni began to crumble. I was intrigued to know what had prompted his interest. I decided to take a look at the video for myself.

Benigni enters the stage on a white horse carrying the Italian flag, greeting the audience with his usual smile. Upon descending from the animal, he tells his first joke: “I was not sure about this entrance,” says the actor, “because these days are not propitious for knights!” The reference is clearly aimed at former Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, who is also known as “Il Cavaliere” because he was awarded a knighthood before he went into politics.

With a serious face Benigni changes the subject: “This evening I am here to talk about the 150-year anniversary of the Italian Republic. In national terms, Italy is just a baby, a minor.” The laughter from the audience can’t be contained, but he goes on, seriously,

“Goffredo Mameli was only 20 when he composed the lyrics for our national anthem, and at that time the age of majority was 21. So he was still a minor. Say what, haven’t we had enough of all the ‘minor’ stories?” Catching this second dig at “Il Cavaliere,” the audience response is off the charts.

Benigni gives the best of himself when he starts talking about “I Carbonari” (the, so called, charcoal burners), a secret revolutionary society that created Italy in the early 19th century.

He quotes Silvio Pellico, who while imprisoned by the Austrians wrote “My Prisons,” a classic pamphlet in the canon of Italian literature. Benigni adds another joke: “Before you get another Silvio, who can write another book like this? Heh!”

With smart satire he carries on to mock everyone on the political scene. Roberto bridges generations with the topic of the evening, in his words, “the exegesis of the Italian national anthem.”

He emphasizes the extraordinary opera that is a key part of adolescence: “They were all kids. Michele Novaro, who wrote the music, was only 26 at the time.

Most of them all died young, but they gave their lives for us!” This raises another round of applause. Piedmont, he reminds the audience, is the region where Italian unification began. But “at first, as they united Italy, the capital was Turin, but then it was immediately moved to Detroit. We don’t understand why they have to move everything to Detroit!” He refers about the fact Fiat bought Chrysler and became FCA. (Fiat Chrysler Automobiles)

“Think! Italy is the only country in the world where the culture was born before the nation! The joy of living in a place one loves. Think!” he carries on . “Think of the sense of belonging that a language creates. Loving it too much is wrong, how many mistakes have been made for being too much in love? You are in love or you are not. It is like being dead or alive: you can’t be too much dead.”

The audience now has tears in their eyes laughing, but hurricane Benigni does not stop. He focuses on the Italian flag, and the patriots who have given the flag meaning. “These people,” he says, “did not live for carpe diem, but for an eternal moment, and nobody could stop them. Cavour, Mazzini, Garibaldi, all three retired poorer than when they entered politics, but they made the Italians richer. Memorable!”

With humility, Benigni is capable of delivering a message of global truth. Political ideology has become a smoke screen for complicated business. So-called “statesmen” become “advisers,” when they have finished their mandates, sitting on the boards of multinationals, banks and hedge funds. It is not difficult the contradiction, if you consider that these “legislators” become the “consultants” to overcome obstacles that they themselves put into place.

The rule of free market became the bible for the economic survival policy of a country dictated by speculators. So what happened to political ideology? Where are the leaders? They do not exist anymore. Politicians are shop assistants for global cartels, administrated by an international cast, en route to jeopardising the wellbeing of future generations. The process, so far, seems irreversible. But, certainly, anyone who thinks that is not true is living on another planet.

During the Italian Renaissance, Metternich said that Italy was merely a geographic notion. That is exactly the perception that big companies have of the globe nowadays.

That’s why the genuine act of love that Benigni gives to the Italian people is to remind them of the nation’s real makers: the poets, the writers, the young people who gave their lives to build up a country with a spirit of belonging. With that subtle message, Benigni says: “Italy was a dismantled country. These kids came up with a hymn, because a poem provides strength. The national anthem represents the solemnity of the Italian population, artistic and allegro, a word that cannot translate into any other language. The allegria belongs only to us.” Benigni paces up and down stage, with his unique way of talking and walking that makes him look like a puppet without strings. His enthusiasm is contagious. The audience receives him, now, on its feet. The standing ovation is not just in appreciation of his humour but, yes, of sharing his point of view.

After the ovation, Roberto quotes the first line of the anthem:

Fratelli d’Italia, l’Italia s’è desta, (Brothers of Italy,Italy has woken.)

“Let’s wake up! There is only one way for your dreams to come true and that is to wake up!”

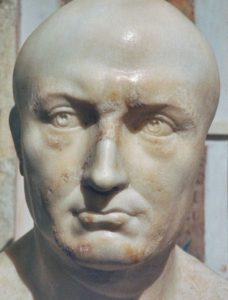

Dell’elmo di Scipio s’è cinta la testa. (Bound Scipio’s helmet Upon her head.)

Italy has put on the helmet of Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus [235-183 BC], the greatest general of all time. He is known for defeating Hannibal at the final battle of the Second Punic War at Zama in 202BC, a battle that changed the destiny of the world. “Scipio,” says Benigni, “was only one of many generals, and still more would come. Julius Caesar, Augustus, Trajan, Hadrian. They invented everything from Roman law to architecture, everything that belongs to the modern world now.”

He continues with the lyrics of the Mameli hymn:

Dov’è la Vittoria?

Le porga la chioma,

ché schiava di Roma

Iddio la creò.

(Let her bow down,

For God created her

Slave of Rome.)

“No city in the world had such an impressive adventure as the city of Rome,” says Benigni.

Stringiamci a coorte,

siam pronti alla morte.

Siam pronti alla morte,

l’Italia chiamò, sì!

(Let us join in a cohort,

We are ready to die

We are ready to die,

Italy has called.

Let us join in a cohort,

We are ready to die.

We are ready to die,

Italy has called, yes!)

Stringiamci a coorte, “the Roman Legion was made up of cohorts,” explains the actor, “6,000 troupes in centuries and they were scary. It was the biggest army in the world at the time.”

Noi fummo da secoli

calpesti, derisi,

perché non siam popolo,

perché siam divisi.

Raccolgaci un’unica

bandiera, una speme:

di fonderci insieme

già l’ora suonò.

(We were for centuries

downtrodden, derided,

because we are not one people,

because we are divided.

Let one flag, one hope

gather us all.

The hour has struck

for us to unite.)

“In those days there was no flag. There were the cockades [rosettes worn as a badge] from the house of Savoy. Giuseppe Mazzini, the founder of Giovine Italia (Young Italy) and Giovine Europa (Young Europe), chose the colour for the Italian flag from a verse by his favourite poet, Dante Alighieri.” And here, Roberto recites the verse from Purgatory where Beatriz appears:

Sopra candido vel cinta d’ uliva donna m’apparve,

Sotto verde manto vestita di color di fiamma viva?

Over her snow-white veil with olive tint

Appeared a lady under a green mantle,

vested in colour of the living flame.

“Find me another country whose flag derives its color from the greatest poet in the world!” In 2009, Benigni toured the globe with The Divine Comedy, the triumph of Italian heritage whose culture and sophistication is never disputed.

Uniamoci, amiamoci,

l’unione e l’amore

rivelano ai popoli

le vie del Signore.

Giuriamo far libero

il suolo natio:

uniti, per Dio,

chi vincer ci può?

(Let us unite, let us love one another,

For union and love

Reveal to the people

The ways of the Lord.

Let us swear to set free

The land of our birth:

United, for God,

Who can overcome us?)

Benigni takes a moment to explain the ideas of Giorberti Catholicism and Liberalism and then moves along to the women of the Italian Renaissance. He mentions the Countess of Castiglione and Cristina Triburzio of Belgioiso, who from their own purses hired an army of mercenaries from Naples to free Milan.Stendhal refers to this in his novel The Charterhouse of Parma (1839). Begnini also talks of the Paolucci, and of Ana Maria “Anita” de Jesus Ribeiro Da Silva (1821–1849), the Brazilian wife of Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Garibaldi,

(Anita Garibaldi)

who died in pregnancy escaping with her husband to Venice, and of Italian mothers who during that time created comities, writing to each other for news of their children in battle.

Dall’Alpi a Sicilia

Dovunque è Legnano,

Ogn’uom di Ferruccio

Ha il core, ha la mano,

I bimbi d’Italia

Si chiaman Balilla,

Il suon d’ogni squilla

I Vespri suonò.

(From the Alps to Sicily,

Legnano is everywhere;

Every man has the heart

and hand of Ferruccio

The children of Italy

Are all called Balilla;

Every trumpet blast

sounds the Vespers.)

The Battle of Legnano between Emperor Frederick Red Beard (Barbarossa), and the Lombard League, was fought on May 29, 1176. In Tuscany, Francesco Ferruccio (1489 –1530) attacked the retreating Charles V. “He was wounded and had malaria. Fabrizio Maramaldo, an Italian mercenary at the service of the Spanish, reached him and killed him. Before succumbing, Ferruccio said his famous phrase: ‘Coward, you kill a dead man!’ At a ball, La Signora Aldobrandini was invited to dance. Her public response to Maramaldo was: ‘Nobody that has an ounce of honour would dare to dance with worm like you!’ That’s what the Italian women were like then,” commented the actor. The audience is as enthused as ever, mesmerised, and at this point I can understand why that kid sent me the message that awoke my curiosity.

Benigni mentions another kid, Gianbattista Perasso, a boy of 14 known as Balilla, who witnessed Austrian soldiers beating Genovesi citizens because they refused to help pull cannons out of mud. The Genovesi knew that those cannons would have been used to kill their fellow compatriots and therefore did not want to help the soldiers. When Balilla saw this, he took a stone and threw it at the soldiers. That stone was the spark that started the insurrection in Genoa against the Austrians. A similar episode, although in a different time, was the war of the Sicilian Vespers ending French domain in 1284.

Son giunchi che piegano

Le spade vendute:

Già l’Aquila d’Austria

Le penne ha perdute.

Il sangue d’Italia,

Il sangue Polacco,

Bevé, col cosacco,

Ma il cor le bruciò.

(Mercenary swords,

they’re feeble reeds.

The Austrian eagle

Has already lost its plumes.

The blood of Italy

and the Polish blood

It drank, along with the Cossack,

But it burned its heart.)

Benigni explains that the reference here is to the mercenaries at the mercy of Austrian money who, together with the Russians, destroyed Poland. But the bloodshed turned to poison, ultimately destroying the Austrian eagle, basically the Austrian empire.

Before bidding goodbye to his rapt audience, Benigni asks their permission for the privilege of singing the national anthem. Like only a few actors in the world can do, he requests that the lights be dimmed and instantly recreates the atmosphere of a lonely boy before a battle, inspired by the poetry of a hymn to fight for his country.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UEk3FbCAZmI

On a stage that has seen the birth of the biggest stars of the Italian music industry, Bocelli, Pausini, Ramazzotti, and Mina, just to name few, Roberto Benigni sings the national anthem a capella.

Well! Seeing this little man, his voice overwhelmed by emotion, and suddenly it was clear to me why this video had become viral. Benigni, in a single evening, returned Italian television to culture, through a history lesson and a lesson in style for everybody in his much-loved nation.

In times of depression it often takes an act of courage to wake up a nation. Benigni, Il Magnifico, is not convincing only because he is the first actor ever to get an Oscar for a non-English speaking role, or because he has made a Woody Allen movie. Those who saw him in Down By Law, a 1986 film directed by Jim Jarmusch, or his La vita è bella (Life is Beautiful, 1997) knows the artist’s unique greatness. He has managed, with the sensibility of a poet, the knowledge of a philosopher, and the humility of great man to bring Italians of multiple generations together.

He might just be a little puppet on stage in comparison to the grandeur of the establishment. But that little puppet, unlike the others, has no strings attached, and with his courageous allegria, like Balilla before him, has managed to wake up a nation with a hymn at heart.

Why do we want talk again about this? Because the country after the last election is split basically in three parts and the wannabe leaders should be reminded of how the country is made historically. That’s a simple act of courage compared what our ancestors have done. So let’s leave aside the differences and bitter rows create during the campaign and work on a new coalition for the country’s sake.

(Let us unite, let us love one another, …….United, for God,Who can overcome us.)

Only in this way Italy can start again.