TBILISI ART FAIR (TAF)

April 19, 2018

ABBA: From Arrival to Revival – Cashtills Ring Out Again

April 28, 2018Discovering the Rebirth of Paris: The Left Bank World of Sartre, de Beauvoir, Lanzmann and Gréco

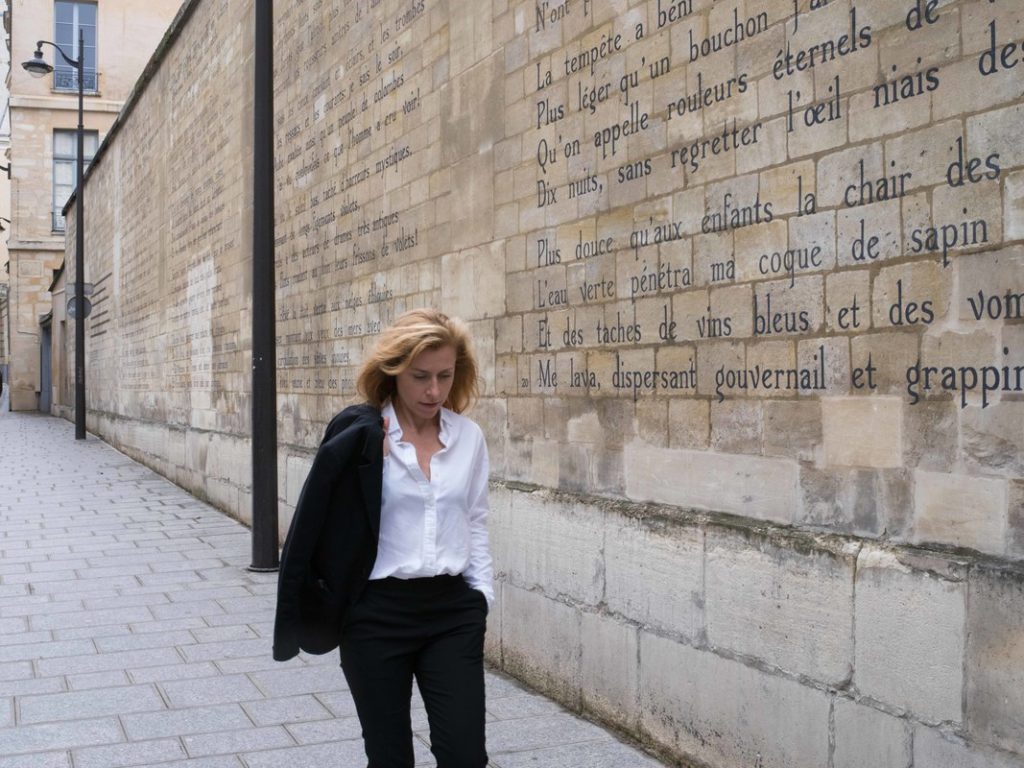

The author at Café Odéon August 2017. Credit Hannah Starkey

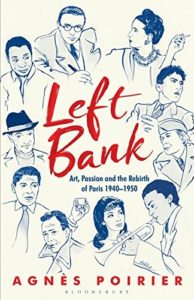

Agnès Poirier is an author and commentator on France in the British and international media. Her new book is called Left Bank, Arts, Passion and The Rebirth of Paris 1940-1950. She covers all of the other mega-talents who roamed Paris – going far beyond Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, Picasso, Cocteau and Miles Davis. DANTE recommends the book as a good read and well documented. We will review it subsequently in our print magazine.

Here, she writes about her research for the book.

By Agnès Poirier

They are either dead, or too alive.

They are recording their latest album, shooting their latest film, writing the follow-up to their memoirs, abroad on an umpteenth “farewell tour”. If they’re not simply too busy playing tennis. The youngest ones are approaching 90, the oldest nearing 105.

When I started researching Left Bank, Arts, Passion and The rebirth of Paris 1940-1950, and a period that is almost 70 years old, I asked myself, what is most urgent? To tackle the archives head on, to identify and locate the protagonists’ private papers, to start reading the 1,000 monographs that may shed some light on the subject, to sift through 10 years of printed press across two continents, or to try to meet the men and women who have lived through those years, the last eyewitnesses, the survivors, the precious primary source that historians so cherish? I ticked the last box: the survivors, of course. I would chase the last survivors of the legendary story I wanted to tell: Paris 1940–50.

I don’t know whether my passion and desire to meet them unwittingly gave them the evil eye, but my first months of research were a disaster. As soon as I had identified a name, and was trying to locate that person through journalist friends, publishers and the phone directory – the way one did it in the 1950s – they would drop dead.

At the end of January 2013, I learnt that Stanley Karnow, an American student and ex-GI turned Time magazine’s Paris correspondent in the 1950s, was still alive. Excited at the news, a second-hand edition of his wonderful memoirs in my hand [Stanley Karnow, Paris in the Fifties (Random House, 1997)], I was thinking of him one morning as I walked across the River Seine, behind Notre Dame cathedral and towards the Île Saint Louis, the place steeped in a morning lavender mist. His picture on the back cover showed a man with a kind face, a receding hairline and droopy eyes, standing probably in a room at the Hôtel Crillon with the windows wide open on to Place de la Concorde. Wearing a dark suit and white shirt, he held a cigarette in his left hand between his index and middle fingers, in a typical 1950s pose.

I walked towards the tip of the Île Saint Louis where, like the prow of a ship, stands the Café Saint Régis. Few tourists who flock to this retro bistro, with its warm lighting and beautiful views, realise that Saint Régis’ booths-for-two are made of 1930s métro wooden benches. I was just 10 in the 1980s, when the old métro coaches, the famous Sprague-Thomson carriages built between 1928 and 1933, stopped being used – dismembered, destroyed, a few sent to the transport museum and some salvaged by flea-market vendors, with the idea of selling bits of brass and wood at the price of gold to soon-to-be nostalgic. Paris is the womb of nostalgia, and in Paris nostalgia is a flourishing industry. I remember the old Paris métro so well: the glossy green paint on the exterior of the second-class carriages and the bright tomato red of the single first-class one, the undulating wooden slats of the benches, the brass double latches on the doors; all the furnishing details were simple, rudimentary even, but elegant. Young girl though I was, I probably shared the same wooden seat as Pablo Picasso’s enigmatic mistresses; the fragile American writer Carson McCullers; the broody novelist Saul Bellow; the handsome jazz genius Miles Davis – but also Gestapo torturers and Resistance fighters, all young, all ruthless in their own way, and only 70 years apart.

Kees Scherer, Paris métro, 1950s

I ordered my first espresso and looked out towards Notre Dame’s arches when, suddenly, I spotted Stanley Karnow’s first wife, the French writer Claude Sarraute, walking on the pavement opposite. A guest on popular talk shows both on radio and television, she is a novelist and the daughter of nouveau roman pioneer Nathalie Sarraute, who hid Samuel Beckett in September 1942. [After Alfred Péron, his best friend and fellow member of the Gloria Resistance group, was arrested by the Gestapo.] A good omen, I thought. I started reading the International Herald Tribune. I looked at the obituary pages – I always do. And here was the intelligent gaze of Stanley Karnow staring back at me: he had died the day before in his house in Potomac.

In those first few months of 2013, the same thing happened probably three dozen times. Soon I stopped counting. Like a prisoner marking off the days on the walls of her cell, I would cross out another name on my long list of people to meet. And so on to the next, a little deflated perhaps, but not defeated. Luckily some of my ‘survivors’, my storytellers, my yellow buoys in history’s ocean, were alive and well. Very alive. And that, soon, proved a problem too. Almost as insurmountable as death.

After dozens of emails, messages and calls to former assistants, ex-best friends and long-time managers of Juliette Gréco, Paris’s Left Bank’s muse and Existentialist gamine No. 1, I was told that Mademoiselle Gréco, aged 86, was recording her latest album. “Contact us next year.” Miss Gréco was not planning on death in the near future; perhaps I would not live long enough to see her.

The next name on my list was Claude Lanzmann, director of the ground-breaking 9 ½-hour-long documentary Shoah in 1986, which took him 10 years to edit, a résistant at 15, the only man who ever lived with Simone de Beauvoir, an intellectual and a womaniser of magnitude and the successor of Jean-Paul Sartre at the head of Les Temps Modernes, the most influential magazine in France at the time. His publisher’s assistant and his own personal assistant were adamant: Mr Lanzmann didn’t have a minute to spare. Lanzmann was finishing the editing of his latest documentary, an almost four-hour-long film about the only Elder of the Jews to have survived the war; Murmelstein, his name was, and he had been in charge of the Theresienstadt concentration camp. Picking from the thousands of hours of footage he didn’t use for Shoah, Lanzmann, 88, was again revisiting the Holocaust, or the Shoah as he’d rather call it, in what was probably going to be another masterful film.

The author Agnès Poirier. Credit Hannah Starkey

I was dealing with extraordinary human beings in the strictest sense of the term: out of the ordinary, larger than life, defying norms, challenging common morality, and to whom usual standards, whether of health or behaviour, don’t seem to apply. Their incredible longevity and their resilience, both physical and mental, matched their talent. The French tend to view these people with unreserved awe and undying love. They have an immeasurable, and perhaps unreasonable, respect for grands hommes and grandes femmes who, as long as they show great talent, deep intelligence and panache, can get away with almost anything.

Poet, playwright and kleptomaniac Jean Genet was famously defended by Jean Cocteau and Jean-Paul Sartre at his trial in 1948 for the theft of an original edition of Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du mal, for which he risked life imprisonment. (At the time, a third repeated offence automatically triggered life imprisonment, or a very lengthy prison sentence at the very least.) Cocteau probably saved Genet from a very lengthy stay behind bars by simply telling the judge: “Will you dare send to prison France’s greatest living poet?” Such defence tactics would not work in any other country but France. They would probably still have an impact today.

What was I to do with all those octogenarians and nonagenarians who either breathed their last as soon as I pronounced their names or who were too alive, thus too busy, to see me? Luck struck on a sunny Paris afternoon in April. The news flashed on my computer screen as I sat on a wicker chair at Café Rostand overlooking the Luxembourg Gardens. Claude Lanzmann’s The Last of the Unjust had been added to the official selection of the 2013 Cannes Film Festival. If the great man was too busy to see a supplicant researcher, he might be willing to be interviewed to talk about his film to The Guardian, for which I regularly wrote.

On 12 May 2013, after carefully watching his film, preparing a set of questions and arriving early back from London, I decided to walk to Claude Lanzmann’s apartment, rue Boulard, a stone’s throw from the Montparnasse Cemetery. I was feverishly checking that I had spare batteries for my audio-recorder when I looked at my watch. I was on U.K. time, I hadn’t reset my watch, I was already late. A formidable 88-year-old Frenchman well known for being irascible was already wondering what the hell I was doing. I ran into the street, hailed a cab, called the assistant, the publicist and the publisher to apologise.

I ran up the staircase to the fourth floor of Lanzmann’s 1950s building, sweating, apoplectic with shame, and rang the bell. On his door his initials ‘CL’ were engraved on a brass plate. I could see my face reflected in it, all red and flushed. I first heard the steps, heavy and steady. Those were not the steps of an old person. The door opened slowly to reveal an ox of a man, in a white shirt and smart navy suit, his red légion d’honneur, the rosette as it is called, shining bright on his lapel and catching my eye, like the beam of a lighthouse in the night.

He was not happy. I apologised profusely in the never-ending British fashion, which however never rings totally sincere in French. Considering whether to throw me out at once or to be magnanimous, and after eyeing me up from head to toe, he condescended to forgive me. He sat me close to him at his desk, which was littered with books, press cuttings and heaps of letters; in the centre was the latest and biggest computer screen I had ever seen. His desk stood in a living room facing south, the walls, leather sofa and glass coffee table disappearing behind hundreds of books. Lanzmann was work incarnate, and in his flat, as I later discovered, there was no room to lounge around or chill out, both concepts that were probably alien to a man who enrolled in the underground Resistance while studying philosophy as a young teenager. In the little space left on the shelves were framed pictures, mainly of Simone de Beauvoir, one of many women in his life but probably the most important, and Jean-Paul Sartre, his mentor and friend; and many awards.

After a respectable 90 minutes dedicated to his film, I revealed the reason behind the interview. I needed him to help me understand and document a time and place, a generation of men and women and politics I hadn’t lived through. I was finishing the 700 pages of his extraordinary memoirs; he was my man. [The Patagonian Hare (Atlantic, 2012), Le lièvre de Patagonie (Gallimard, 2010).] He accepted with a gracious smile; we would meet again after the Cannes Film Festival. We said goodbye, but instead of shaking hands he kissed mine. I was soon going to get to the heart of my subject.

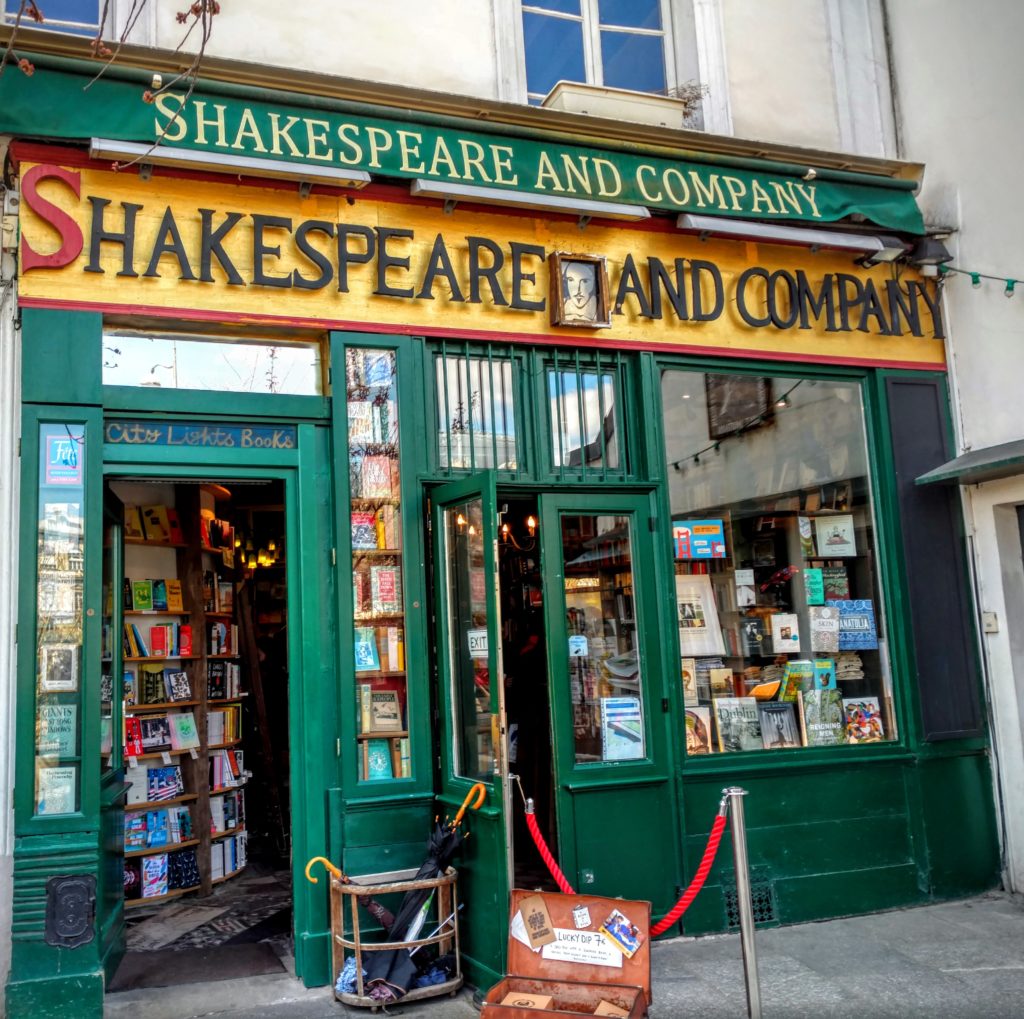

The store is small and it has moved. It remains one of the most famous bookshops in the world.

***

I was in the crowd outside the Debussy Theatre at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival where The Last of the Unjust was shown for the first time both to the world’s critics and the film industry. Coming out of a black limousine and wearing the obligatory tuxedo, he was flanked on his left by his charming Swiss companion, 25 years younger, and on his right by the equally beautiful Valérie Trierweiler, briefly First French Lady. I saw him walking up the red-carpeted 35 steps to the theatre without needing to pause for breath.

His film was received with reverence. The day after the screening, the French daily newspaper Libération chose a black and white close-up of Lanzmann’s face to cover the entire front page, with the headline: Un Film Testament.

Testament? Lanzmann must have smiled at the somewhat predictable title. A man his age could only be showing his last film. Libération had misread both the film and the man. Lanzmann was in rude health and had no intention of letting go. And his film may have come from unseen footage from Shoah, whose subject is undoubtedly death, but it was not a testament. If anything, The Last of the Unjust, although about the Holocaust, was about the miracle of life, the miracle of survival. As film critic Richard Brody wrote a few months later in The New Yorker, “It’s a miracle that anyone came out of the camps alive. It’s a miracle that Murmelstein, the Elder of the Jews and Last of the Unjust, in his position of terrifying proximity to barbaric overlords, was able to save as many Jews as he did – and to save himself. It’s a miracle that Judaism itself, as a religion and an ongoing element of history, survived.” (The New Yorker, 27 September 2013.)

A few days after the screening, as I was on the train heading back to Paris from Cannes, my phone rang. “Come and have dinner with me tomorrow evening. I’ll cook a Bresse chicken. You don’t have anything against Bresse chicken, do you?” [“The only chicken in the world to be protected, like a famous wine, by an Apellation d’Origine Controlée … As a result of that tradition it has the tastiest, the firmest and most succulent flesh of any chicken anywhere … if you go to any three-star Michelin restaurant today, the chicken dish will invariably be poulet de Bresse.” John Henley, The Guardian, 10 January 2008.] He didn’t need to say his name. It was Lanzmann, whose inimitable voice comes from a far-off time and place. It is strong, low and hoarse, like rolling rocks. He speaks the way he writes, flawlessly, with a perfection of grammar and a careful delivery that doesn’t exist any more and must surely be God-given.

I loved Bresse chicken, but I settled for Sunday lunch rather than Saturday dinner as a more “respectable” time and day, I thought, already a little weary. Lanzmann has a reputation. A year earlier, in February 2012, he had been briefly arrested for sexual harassment at Ben Gurion airport. He had kissed a young and pretty Israeli security officer against her will. Anyone knowing the humourless process of Israeli security checks at airports can only wonder what the hell he was thinking when he tried to steal a kiss from a security officer. Did he reckon he was too important a figure to get into any kind of trouble, or is it that, being of his generation, he simply cannot grasp the concept of sexual harassment? Probably both.

I brought a bottle of Vacqueyras, which pleased him. [A wine from the southern Rhône region. Its more prestigious siblings are Châteauneuf-du-Pape and Gigondas.] His 19-year-old son, Félix, who lived with his mother in the flat below, had helped him cook and set the table with a beautiful white damask tablecloth and assorted napkins. He gave me a tour of his two-bedroom flat, which he had found in a rush in the early 1970s as he embarked on his epic 10-year-long journey shooting and editing Shoah. In fact, he just needed a space to store his editing material. He never meant to stay. Forty years later, though, he was still there, a tenant for life, having outlived his landlord. Like Jean-Paul Sartre, his mentor, he never bought a property. No strings, as in the Irving Berlin song, but with connections.

Lanzmann wanted to talk about Steven Spielberg, whom he had just met in Cannes (Spielberg was president of the jury). “I shook his hand and Spielberg said, don’t you hate me?” When Schindler’s List came out, Lanzmann was one of its fiercest critics. “I told him that I didn’t hate him or his film; my criticism of it was ontological, not personal.”

Lanzmann wanted to talk about Steven Spielberg, whom he had just met in Cannes (Spielberg was president of the jury). “I shook his hand and Spielberg said, don’t you hate me?” When Schindler’s List came out, Lanzmann was one of its fiercest critics. “I told him that I didn’t hate him or his film; my criticism of it was ontological, not personal.”

I raised the subject of my research. And Lanzmann brought me a blue folder. Inside were the first letters he had received from French luminaries about his film, from the historian Pierre Nora, writer and high-up civil servant Marc Lambron, art critic and writer Catherine Millet of The Sexual Life of Catherine M. fame – the list was long and the praise flowing and springing from page to page.

Lanzmann was not interested in reminiscing about his youth. He was too busy living the present to the full. He wanted Steven Spielberg to adapt his memoirs for the big screen. Months earlier, before Cannes, he had flown to New York, gone straight to the DreamWorks office, Spielberg’s production company, giving his name and asking to see the American director at once, the way things were once done. Steven Spielberg was not in town that day. Never mind, Lanzmann would keep trying. And now that they had finally met in Cannes, he was adamant: Spielberg was the man to film his life.

Lanzmann was also planning his summer holiday, two weeks off Spain’s Costa Brava “to swim”, and another fortnight in the French Alps, in Chamonix, “to hike”. I suggested we took a stroll towards the Montparnasse Cemetery and the rue Schoeller, where he lived with Simone de Beauvoir. Perhaps this would lead him to think about the past a little. Once down rue Boulard, I was intrigued by a message repeatedly stencilled in white on the grey concrete pavement, like Hansel and Gretel’s breadcrumbs. It read: Félix, Je t’aime. Felix Lanzmann, Claude’s 19-year-old son. A girl, madly in love with him, had stencilled the same message on the pavement over half a mile, from the métro to their building.

Walking up rue Boulard, Lanzmann père started reciting in my ear some Alfred de Vigny, the great 19th-century romantic poet and Victor Hugo’s best friend, but his feet hurt. I walked him back and took my leave. We were now on cheek-kissing terms. Before shutting his door he asked, “Are you the faithful kind?” “It is the one question I never give an answer to”, I replied, not knowing what I meant. In fencing they call it pas de touche.

I saw Claude Lanzmann once more, this time for dinner. Our last tête-à-tête took place in his kitchen, left unchanged since the 1950s, its walls covered with the tiniest sky-blue ceramic tiles. I enjoyed his conversation immensely – how could I not? – I loved his voice, his language, his brilliance. However his egotism, obsession with the present and his too-frequent attempts at kissing me left me with no other choice than to cross his name from my list. Lanzmann, almost 50 years older, was too alive for me.

Yet this strangest of encounters, with a genius octogenarian, his ego as big as his libido, did reveal to me what was to prove one of the central themes of the story I was to tell. Those young men and women who had known the horrors of war all shared this insatiable appetite for life, for breaking free from traditions and from a morality they refused outright.

***

U.S. cover

On a rainy morning in January 2014, I boarded the double-decker TGV train from Paris to Toulon, feverish and with a very bad cough. I felt elated, though. I was on my way to St Tropez, to spend the day with Juliette Gréco. I had tried to contact her for almost a year through different means and kept hitting a brick wall. No audience could be granted with the Existentialist muse: she was too busy recording her latest album, Gréco Chante Brel. And then she was going to tour Europe.

The release of her album in Britain allowed some hope, and eventually, it seemed, the opportunity of a lifetime. Just tell me where and when and I’ll be there, I told Universal Classics, her recording company. Classics? I was surprised she should find herself alongside Brahms and Debussy, though the more I thought about it, the more it made sense: Gréco is a little like those statues in the Louvre, classic and monumental. The answer came quickly: next Tuesday, chez Juliette, in St Tropez.

I had read her autobiography, Jujube (her childhood nickname), a cryptic and alert first-person impressionistic account of her life, which had both charmed and frightened me. [Juliette Gréco, Jujube (Editions Stock, 1982).] The lady didn’t suffer fools easily. The men who tried to commit suicide (and some actually succeeded) after she failed to return their calls in the middle of the night were, in fact, littering the floor of her life. If there ever was a femme fatale in post-war Paris, Juliette Gréco chillingly and magnificently qualified. The jazz trumpeter Miles Davis was one of many who never recovered from Juliette, whom he met at his first Paris concert in 1949. She could be as harsh with women as she was with men. In other words, Gréco had a reputation for being tough. Perhaps she was like her mother, a résistante and survivor of Ravensbrück concentration camp, who after her return from Germany almost immediately volunteered to serve in the Indochina war waged by France. My nine-hour train journey might end up with a five-minute encounter on her doorstep.

The road from Toulon to the St Tropez heights where she lived part of the time was almost completely deserted. The 43-mile journey up the hills, through the thick and luscious Mediterranean vegetation, in fine drizzle and heavy mist, felt like a dreamy voyage to another world. We kept driving up on winding roads and finally found, at the end of a private road, Juliette’s den, built on the hillside.

Dolorès, the Spanish maid, opened the door. Ushered into a vast whitewashed room giving on to a terrace with lemon trees, overlooking the neighbouring hills and the sea, we sat by a huge open crackling fire right in the middle of the room. White sofas and black African masks completed the Olympian décor.

Juliette Gréco and Agnès Poirier, St Tropez, 7 January 2014 © Grégoire Bernardi

And then she appeared, in her signature black. A black so intense it proved difficult to distinguish what she was wearing. Against the whiteness of the walls, the floor and the furniture, I squinted, dazzled. Finally I could make out a pair of fluid, elegant trousers and a black cashmere top. Her ink-black hair and her kohl eyeliner contrasted sharply with her white powdered face. She looked fresh and terribly youthful, especially when talking. Her voice had aged only slightly; it was still very low and warm, mysterious and hypnotic, like the snake Kaa’s in Jungle Book, who serenades Mowgli into a trance. Her vocabulary was that of the Left Bank gamine she never ceased to be, using argot from the 1930s, both imaginative and colourful. How refreshing the past may sometimes feel.

We had just started talking of the month of October 1943 when, just after being released from the infamous Fresnes prison, separated from her older sister and her mother, both arrested by the Gestapo and sent to Ravensbrück for their Resistance activities, she found herself alone on the pavement in just the blue cotton dress she had been wearing on the day of her arrest a few months earlier. With nowhere to go, the 16-year-old started walking the eight miles to Paris just to keep from freezing during one of the coldest winters on record.

Gréco’s mobile phone suddenly broke into a mad dance on the sofa, vibrating and giving out the most piercing tone. What on earth was this? A Jacques Brel song in Korean.

While walking towards Paris on that dreary day, clutching at her spring dress, she remembered a friend of her mother’s, Hélène Duc, a celebrated theatre actress, who lived in a decrepit and discreet boarding house, 20 rue Servandoni, near Saint Sulpice church. Night had fallen, the narrow Servandoni street was plunged into darkness; Juliette knocked at the door of the boarding house. Hélène Duc opened it, looked at Juliette and understood her plight immediately. After quickly checking that nobody else was in the street, she let Gréco in. Hélène Duc would later be honoured as “Righteous Among the Nations” for saving the lives of many Jews during the war.

With nothing to wear, hungry and cold, Juliette Gréco spent long hours under the covers: “I stayed in bed for the next two years.”

Juliette Gréco aged 21 photographed by Robert Doisneau in 1948, opposite Saint Germain des Près church. The dog is that of film designer Alexandre Trauner.

***

Meeting history in the flesh, through the men and women who made it, was always going to be an education. I hadn’t however expected the past to assault, as it were, my every sense, nor had I realized that memory, even of those direct witnesses, would prove such a perilous terrain. One says only what one wants to say, and one’s truth is not the whole truth. Speaking to survivors is more interesting for what they conceal than for what they reveal.

Meeting them was the best and most unexpected introduction into an incredibly sensual and dangerous period of post-war history. And I could finally start researching Left Bank, a portrait of the budding novelists, philosophers, painters, composers, anthropologists, theorists, actors, photographers, poets, editors, publishers, and playwrights born between 1905 and 1930, who lived, loved, fought, played, and flourished in Paris between 1940 and 1950 and whose intellectual and artistic output still influences how we think, live, and even dress today. After the horrors of war that shaped and informed them, Paris was the place where the world’s most original voices of the time tried to find an independent and original alternative to the capitalist and Communist models for life, arts, and politics — a Third Way.

They promised themselves to reenchant a world left in ruins and Left Bank would be the story of their lifechanging synergy.

For me, writing this story would prove like walking into a house on fire. The live fire of the war, the furnace of emotions, the passion of politics, the spectacular fallingsout, the brutal sex, the nerveracking frustrations, the insane and beautiful ideals, the plotting of big schemes — so many failures and some remarkable achievements.

“Left Bank” was published by Bloomsbury on March 8. Priced £25 in the U.K. It is published by Henry Holt in the U.S. at $30.

What the U.K. publisher says: https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/left-bank-9781408857441/

What the U.S. publisher says https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781627790246

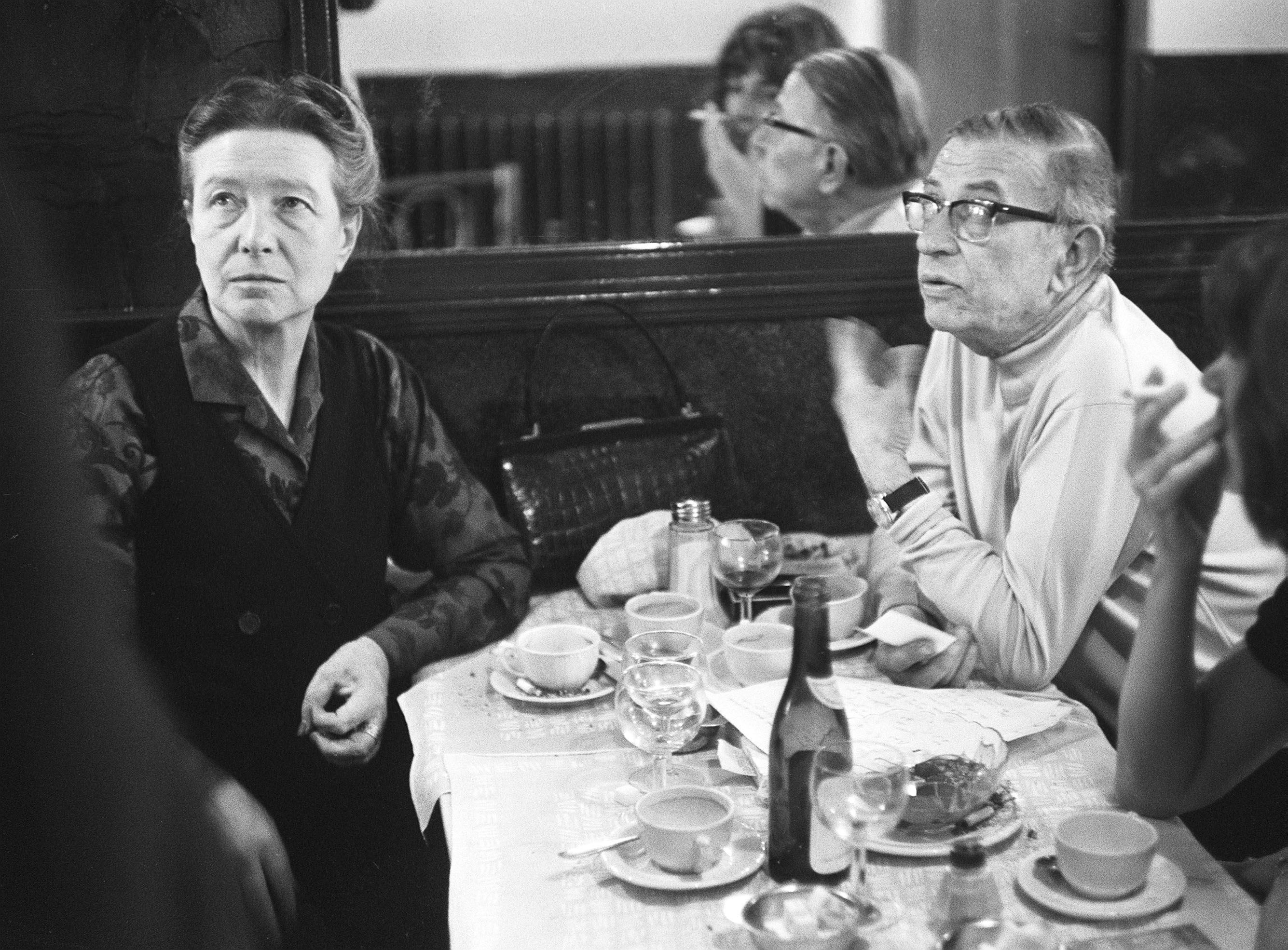

The younger Sartre and de Beauvoir

Café life: Writers Simone de Beauvoir and Jean Paul Sartre in the 1970s

Editors George Ashridge, Mark Beech

The spring edition of DANTE is now in larger WHSmith, Selfridges and independent newsagents. This website has a link to subscribe to that and future editions. We also have a phone app and are in selected airport lounges.