River of words for a Eurovision tale.

May 4, 2018

Julia Munsey at the Royal opera Arcade Gallery

June 4, 2018By Mark Beech, DANTE editor

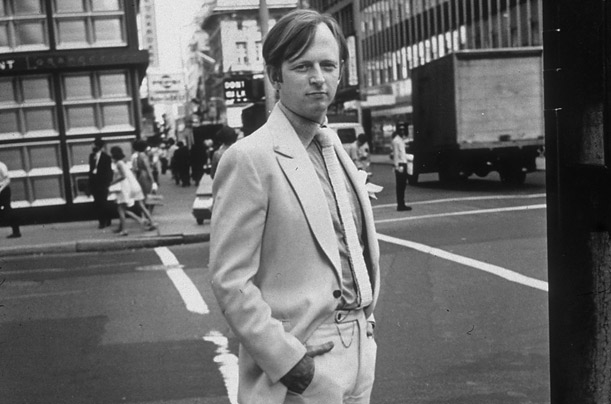

My first encounter with the works of Tom Wolfe came from a most unusual source. Not one of his favoured American publications or indeed some of his more famous books, but from, I believe, an edition of Britain’s Daily Telegraph magazine. Or it may have been one of the British newspaper Sunday supplements in the early 1970s. Either way, I was immediately arrested by his anecdotes and imagery. Wolfe is telling the story of the birth of “radical/funky chic” and how we came to discover it. He relates an incident in a restaurant washroom, in London as it happens, where a man enters, proceeds to completely rip open his shirt and turn his hair into a state of complete dishabille. Only once he has shed formality and become as scruffily radical as possible does he feel chic enough for the evening’s energetic radical activity, which presumably consists of a lot of “turn up, talk crap, go home.”

I remember the article decades on. I recall that it was littered with the same sort of studied informality, a sort of sub-editor’s worst nightmare. Sentences seemed like a stream of consciousness, dashed off in a Jack Kerouac mess of thoughts — whereas in fact some had obviously been very carefully crafted.

But that was in essence the Tom Wolfe style. However one defies defines “new journalism,” which ran in parallel with the “gonzo journalism” of Hunter S. Thompson and others, it was not as casual as it appeared. There was a lot of clever crafting to get it to that state. In the same way as the guy removes his tie in the restaurant washroom and affects to be as spontaneous as possible, Tom Wolfe was a craftsman who kept his sometimes studied poetry hidden under a veneer of machine-gun typewritten informality. Just look at those sentences, littered with sub-clauses, exclamation points and bizarre connections. This was like the work of somebody had gone overboard on absinthe, cocaine, carrot juice, or some weird and wonderful drug or intoxicant. For all that, Tom Wolfe was way too professional (and I hesitate to use that word because it makes it sound like this was totally studied) to overindulge when it came to indulging his writing.

But that was in essence the Tom Wolfe style. However one defies defines “new journalism,” which ran in parallel with the “gonzo journalism” of Hunter S. Thompson and others, it was not as casual as it appeared. There was a lot of clever crafting to get it to that state. In the same way as the guy removes his tie in the restaurant washroom and affects to be as spontaneous as possible, Tom Wolfe was a craftsman who kept his sometimes studied poetry hidden under a veneer of machine-gun typewritten informality. Just look at those sentences, littered with sub-clauses, exclamation points and bizarre connections. This was like the work of somebody had gone overboard on absinthe, cocaine, carrot juice, or some weird and wonderful drug or intoxicant. For all that, Tom Wolfe was way too professional (and I hesitate to use that word because it makes it sound like this was totally studied) to overindulge when it came to indulging his writing.

So now I’m sitting down dictating in a few thoughts, Wolfe style — though he was adverse to computers — on one of the writers who I, along with many others, genuinely admire. Never been much of a fan of anyone, but I confess to liking much of his wayward brilliance.

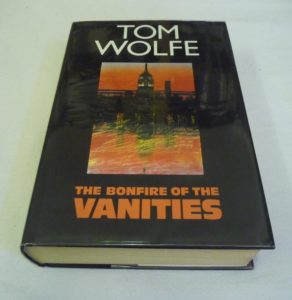

I have just about never gone along to a book signing, for example, apart from my own limited affairs, but I was tempted in the 1980s when Wolfe came to London and was signing copies of his first and best novel, The Bonfire of the Vanities. I had intended to be there in good time but events conspired against me, especially with a Tube (subway) dispute, and amid much cursing I emerged from the underground just as the event was finishing. I got there to find that the white-suited great man had already left the building. Fortunately there were still plenty of people milling about and Wolfe had left a stack of copies signed but without individual purchasers’ names. So I am the proud owner of a first edition of this stunning book signed by the man himself. It is of little consolation on the sad day of his death to reflect that his passing means that it’s probably worth a little bit more.

From the time of discovering Radical Chic, I started to loop back into Wolfe’s earlier works, most of them as chaotically bizarre and brilliant as the titles: The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby (1965), The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968), Mauve Gloves & Madmen, Clutter & Vine (1976). I struggled to get them from my local library in rural England, where readers were more like to go for Laurie Lee, Fred Archer, Catherine Cookson, or Pam Ayres.

It will be fair to say that while The Bonfire of the Vanities in 1987 went on to be a great film satirising yuppies and more, Wolfe’s subsequent novels were not quite of the same standard. While Bonfire is something of a flashy masterpiece, and a friend has long compared it with the similarly monumental A Suitable Boy by Vikram Seth, Wolfe’s finest achievements may indeed lie elsewhere, particularly in his nonfictional 1979 work The Right Stuff. This was of course also filmed and describes how test pilots in the U.S. were chosen to become the first astronauts and it is based on direct research from these men and their families.

It will be fair to say that while The Bonfire of the Vanities in 1987 went on to be a great film satirising yuppies and more, Wolfe’s subsequent novels were not quite of the same standard. While Bonfire is something of a flashy masterpiece, and a friend has long compared it with the similarly monumental A Suitable Boy by Vikram Seth, Wolfe’s finest achievements may indeed lie elsewhere, particularly in his nonfictional 1979 work The Right Stuff. This was of course also filmed and describes how test pilots in the U.S. were chosen to become the first astronauts and it is based on direct research from these men and their families.

I suspect it’s too early to make a distanced, objective assessment on where Wolfe will lie in the literary canon. To some, and yes, including this writer, his literary techniques were influential and his stimulation of what he called the “new journalism” was incalculably important.

There would be those, on the other hand, who would argue that he was much too showy, from the trademark white suit onwards, and he would have done much better to have cut down the flamboyance in favour of substance. It would be pretty inconceivable that he would ever be a serious contender for a Nobel Prize, for example, they say.

Wolfe was of course aware that his look and style were among the reasons he became famous, and there is no doubt that he always wanted this notoriety and money. I will leave the last quote to him which sort of sums up his appeal: “People complain about my exclamation points, but I honestly think that’s the way people think. I don’t think people think in essays; it’s one exclamation point to another.”