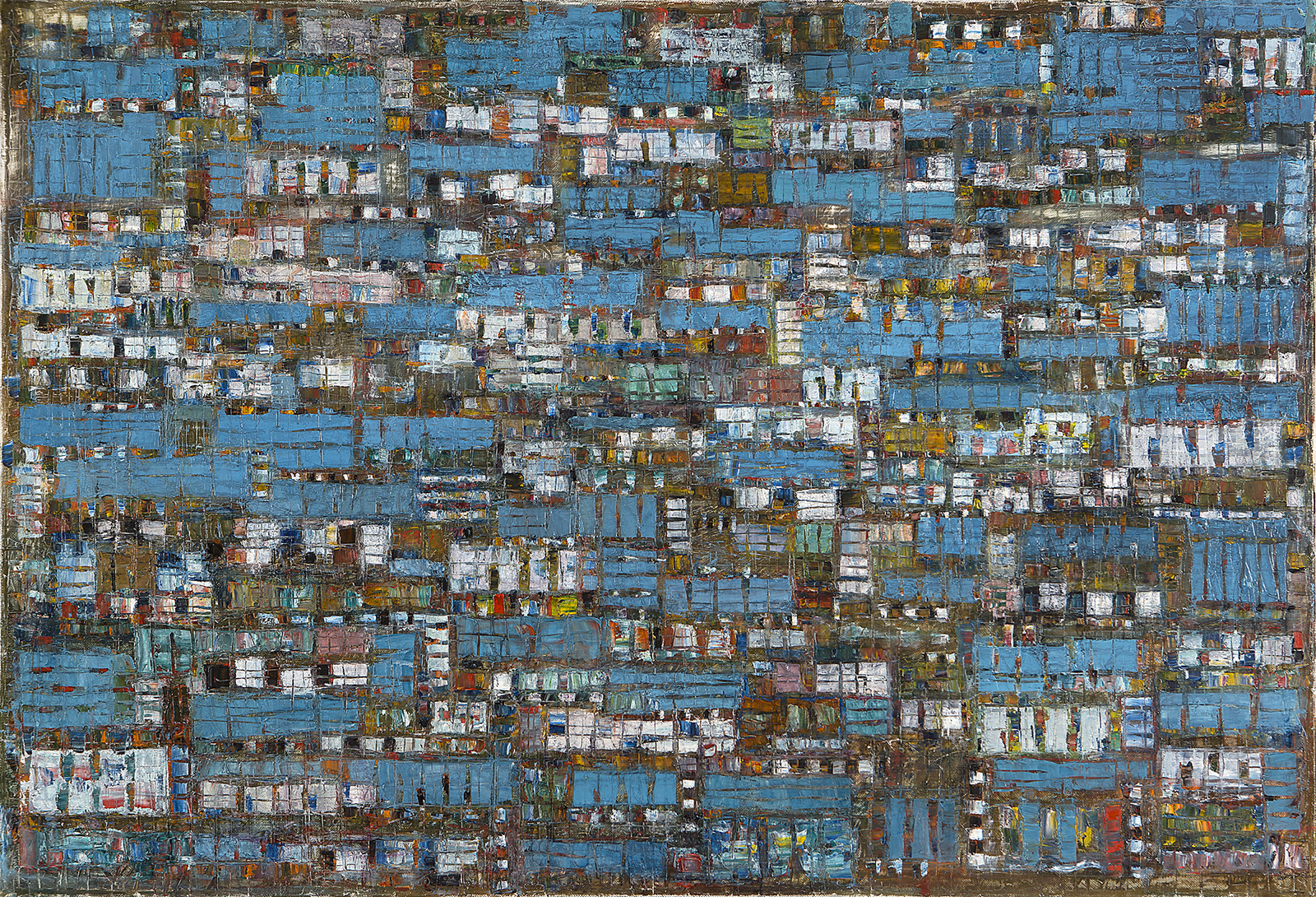

LEVAN LAGIDZE, the iconic Georgian painter, returns to London.LONDON

November 4, 2018

Oh Yes It Is! Oh No It’s Not! – The Great Muslim Panto?

December 22, 2018Pano Masti’s latest literary pilgrimage takes him to Jordan. Never mind Oscar Wilde or T. E. Lawrence, the words that echo in his mind are from women: Marie Colvin, Martha Gellhorn, Gertrude Bell and Agatha Christie.

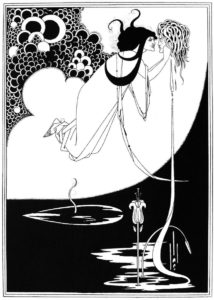

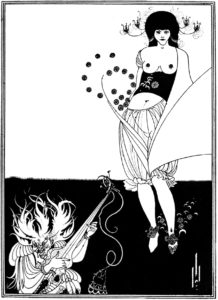

A spectacular super-moon is rising over the eastern desert, blood-orange red, massive and burning. I am transfixed. Look at the moon! How strange the moon seems! She’s like a woman rising from a tomb! is what comes to mind, words from Oscar Wilde’s masterpiece play Salome, in which he employs the abused yet defiant and sexually overcharged biblical female figure to stick it to Victorian society.

I’m in Jordan, not far from the remains of Herod’s palace where Salome danced, my actor’s hat on, arriving on set to work on a film about American war correspondent Marie Colvin and I can only look at the moon. She’s like a dead woman.

Marie Colvin died in Homs, Syria, a few hours’ drive from here, at the beginning of the war. She had spent much time in the Middle East and through her crisp, detailed and committed writing for the British Sunday Times, she reported the atrocities of war and the suffering of civilians trapped in never-ending conflicts. Covering a war means going into places torn by chaos, destruction, death and pain, and trying to bear witness to that, she wrote in 2001.

Jews from Jerusalem are tearing each other in pieces over their foolish ceremonies… barbarians drink and drink… Greeks from Smyrna with painted eyes and silent, subtle Egyptians and Romans brutal and coarse is whom Wilde’s Salome is running away from because she can’t breathe amongst them, and it seems that little has changed since.

My work in the film wrapped, I hire a car and employ my Athenian driving skills to take me out of the chaotic Amman traffic as I head to the rolling hills of northern Jordan and to one of the best preserved Roman cities in the eastern Mediterranean, Jerash, or the land of Gilead as it is often referred in the Old Testament. The site is monumental, the display of craftsmanship in the two theatres, the temples and the agora breath-taking, and an atmosphere of vibrant and never ceasing city life still present.

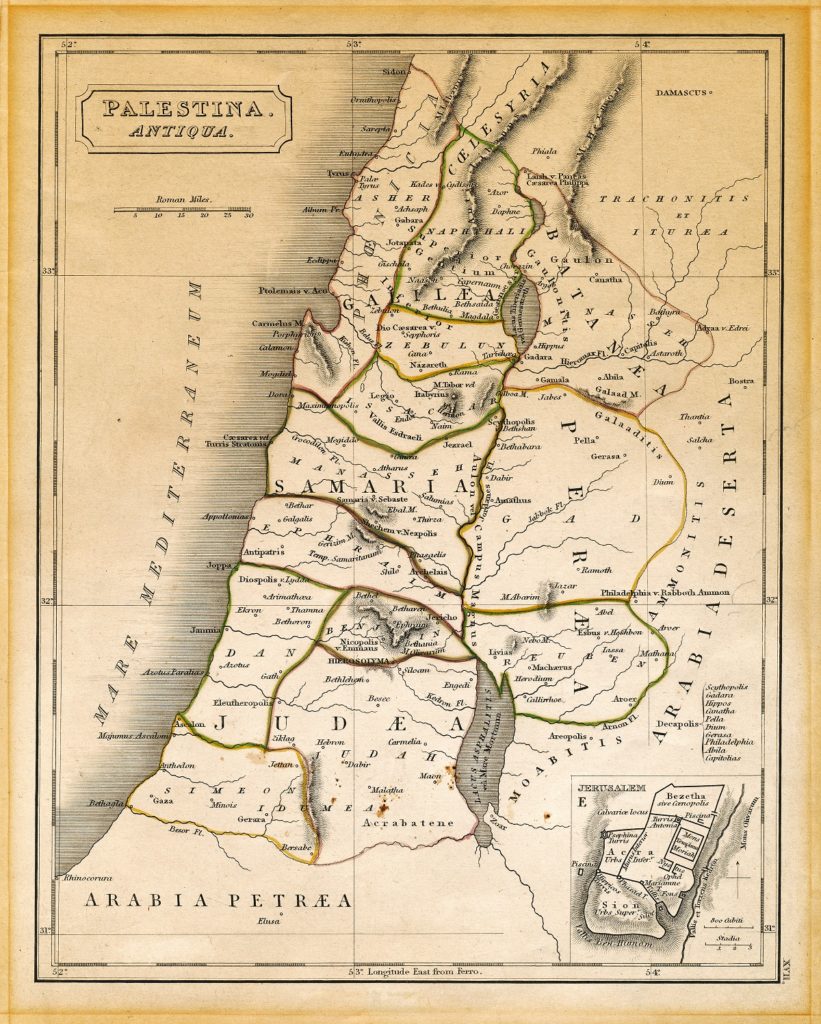

An old 19th century map, engraved and printed in England in 1845, depicting ancient Palestine (‘Antiqua Palestina’ as it’s written on the map itself) at the times of Jesus Christ, from Damascus in the north down to the land south of the Dead Sea in the south. On the bottom right corner there’s an enlargement of the old city of Jerusalem.

Not far from Jerash, the Ajloun castle is abandoned not just in time but also in mist and rain today. The castle was part of a network that allowed medieval Arabs to perfect the art of communication; a message carried by pigeons would be delivered from Damascus to Cairo in an astonishing 12 hours.

From 766 metres above sea level where the castle stands, I drive to 430 metres below sea level, to the deepest place on earth, the shores of the Dead Sea. The water is choppy but warm. I give myself into the unreal floating it offers and as I admire the sun setting over Israel and the West Bank I think of Martha

Gellhorn, another renowned American war correspondent whose work The Face of War Marie Colvin had always by her side. Gellhorn was concerned with the Palestinian refugee crisis in the early 1960s and visited the camps of the West Bank, which was annexed by Jordan at the time. The writing style of Gellhorn was unique; more than anything she gave context to people’s suffering. In her story The Arabs of Palestine published by The Atlantic she points out how more than 600,000 Palestinian refugees live in Jordan, more than in the other host countries put together but the refugees here are full citizens of Jordan. In another part of the piece, she struggles to understand the meaning that the word country has for the refugees. I finally realised that country means town or village; when the Arab peasant refugees talk of their country they’re talking about their own village, their birthplace.

These ideas about the relationship the Arabs of the Middle East have with country and town are with me as I drive south of the Dead Sea towards Aqaba and in the still of the night all I can see is Israeli cars driving past on a motorway a stone’s throw away across the desert on the other side of the invisible border.

From Aqaba I reach the magnificent part of the desert that is Wadi Rum. This is T. E. Lawrence territory and his words in Seven Pillars of Wisdom echo through my visit here. Rum was vast and god-like, he writes, and when a Bedouin wakes me up at dawn to drive me with a 4×4 to see the sunrise, I find T. E. Lawrence’s words spot on. The rising sun flooded this falling plain with a perfect level of light, throwing up long shadows of almost imperceptible ridges… we grew self-conscious and fell dead quiet. This is the landscape that David Lean used in the 1962 classic Lawrence of Arabia that won many accolades including the Oscar for Best Picture and Best Cinematography for Freddy Young who captured so effectively the immensity of this inspiring place.

For all its artistic merits, Lawrence of Arabia is a movie in which the absence of female characters is astonishing. Yet the reality was far from that. Before T. E. Lawrence came to Arabia and for a long while after he left, a friend of his, Gertrude Bell, was known as the female Lawrence of Arabia. Mountaineer, archaeologist, Arabist, writer, poet, linguist and spy, Bell dedicated her life to the Arab cause and was instrumental in shaping policy at the region. [Editor’s note: Regular readers may remember that we told the story of Bell at length in a recent edition of DANTE.] Some day I hope the East will be strong again, she writes, and develop its own civilisation, not imitate ours, and then perhaps it will teach us a few of the things we once learned from it and have now forgotten, to our great loss. If Bell’s words come across a bit dated, it’s worth pointing out that she was a fierce critic of the West too. We share the blame with France and America for what is happening, she writes in 1920. I think there has seldom been such a series of hopeless blunders as the West has made about the East.

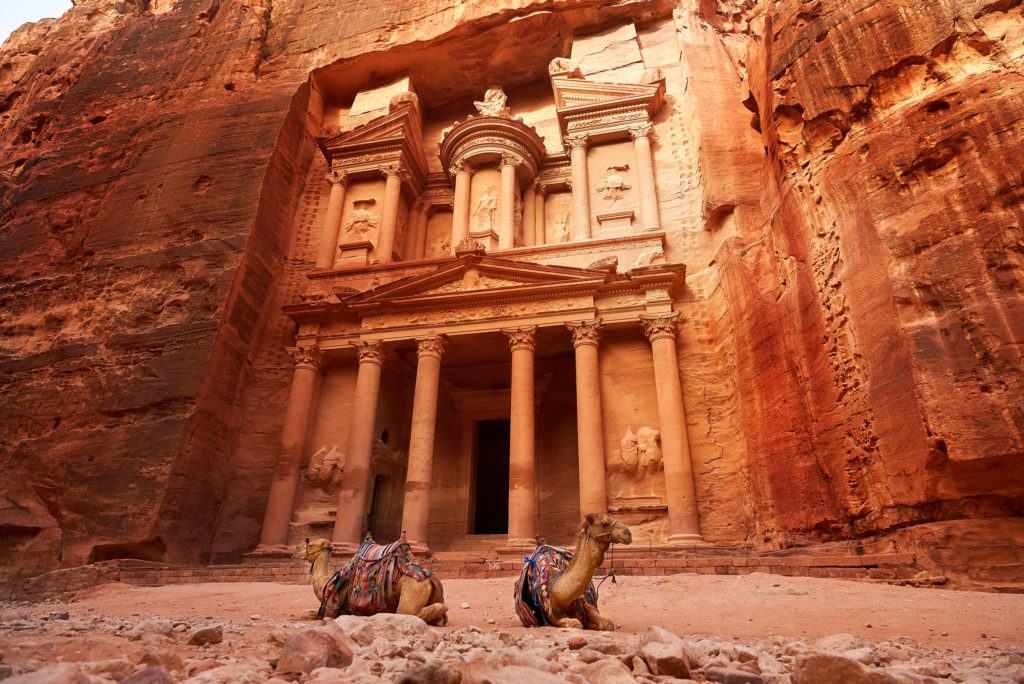

Gertrude Bell travelled extensively in the Middle East, so I follow her steps to the best that I had saved for last, the shiniest example of what a human civilisation can achieve, the Nabatean city of Petra. Suddenly between the narrow opening of the rocks, writes Bell as she visits Petra for the first time, we saw the most beautiful sight I have ever seen. Imagine a temple cut out of the solid rock, the charming façade supported on great Corinthian columns standing clear, soaring upwards to the top of the cliff with the most exquisite proportions and carved with groups of figures almost as fresh as when the chisel left them – all this in the rose red rock, with the sun just touching it and making it look almost transparent. A rose-red city half as old as time. I stand in front of the Treasury, as it is now believed to have been, with tears in my eyes. But the big surprise comes when I go past the Treasury and it suddenly hits me, how massive this place is. The theatre, the temples, the tombs, the roads go on and on. I hike to the top of summits over the city that’s built in deep and hidden canyons and go back down to discover new mysterious ways in this metropolis where Nabateans lived together with Arabs, Greeks, Romans, Jews and Bedouins.

The mystery of Petra is what probably drew here as well the queen of crime writing and Middle East frequent adventurer, Agatha Christie. Appointment with Death is the title of the novel in which a rich American family led by an oppressive matriarch arrives at Petra. With an insatiable appetite to explore, Christie’s characters arrived at the summit. Sarah (the young protagonist) drew a deep breath. All around and bellow stretched the blood-red rocks; a strange and unbelievable country unparalleled anywhere.

Here in the exquisite pure morning air they stood like gods, surveying a baser world – a world of flaring violence. Sure enough, within a day in Petra the old matriarch is found dead and Hercule Poirot is called to solve the mystery.

The sun is setting over Petra and the ruins are on fire. I can’t have enough of this astonishing spectacle and I can’t decide whether the rocks are rose red as Gertrude Bell describes them or blood red according to Agatha Christie. I drive back to Amman on the dark desert highway. Marked by the female voices I followed, my visit to Jordan comes to an end.