Joseph Tawadros. Breaking Boundaries With the Oud

April 12, 2019

It’s Eurovision Time 2019!

May 13, 2019Cape Town has recently held another successful art fair but Heidi Erdmann asks whether the financial stakes involved are undermining their representative nature and clouding correct attribution of art works that auction houses exploit.

A friend once told me that during the Miami art fair week, she made several sales while swimming. She met a collector at a party at a home with a swimming pool and made a sale in the pool. On another occasion, at a beach party, she met a collector while taking a dip, and clinched the deal while catching a wave. I have a visual clip of her in my mind, walking out of the sea, brushing back the strands of hair in her face, smiling broadly. Then very business-like, she dries her hands, pulls the computer from her bag, generates the invoice and presses the send button. Slips the computer in her bag, smiles and says to herself: “Now I really need a glass of champagne”. It’s true, on all accounts, the tale, the plentitude of parties during any art fair week and the significance of a sink-or-swim scenario.

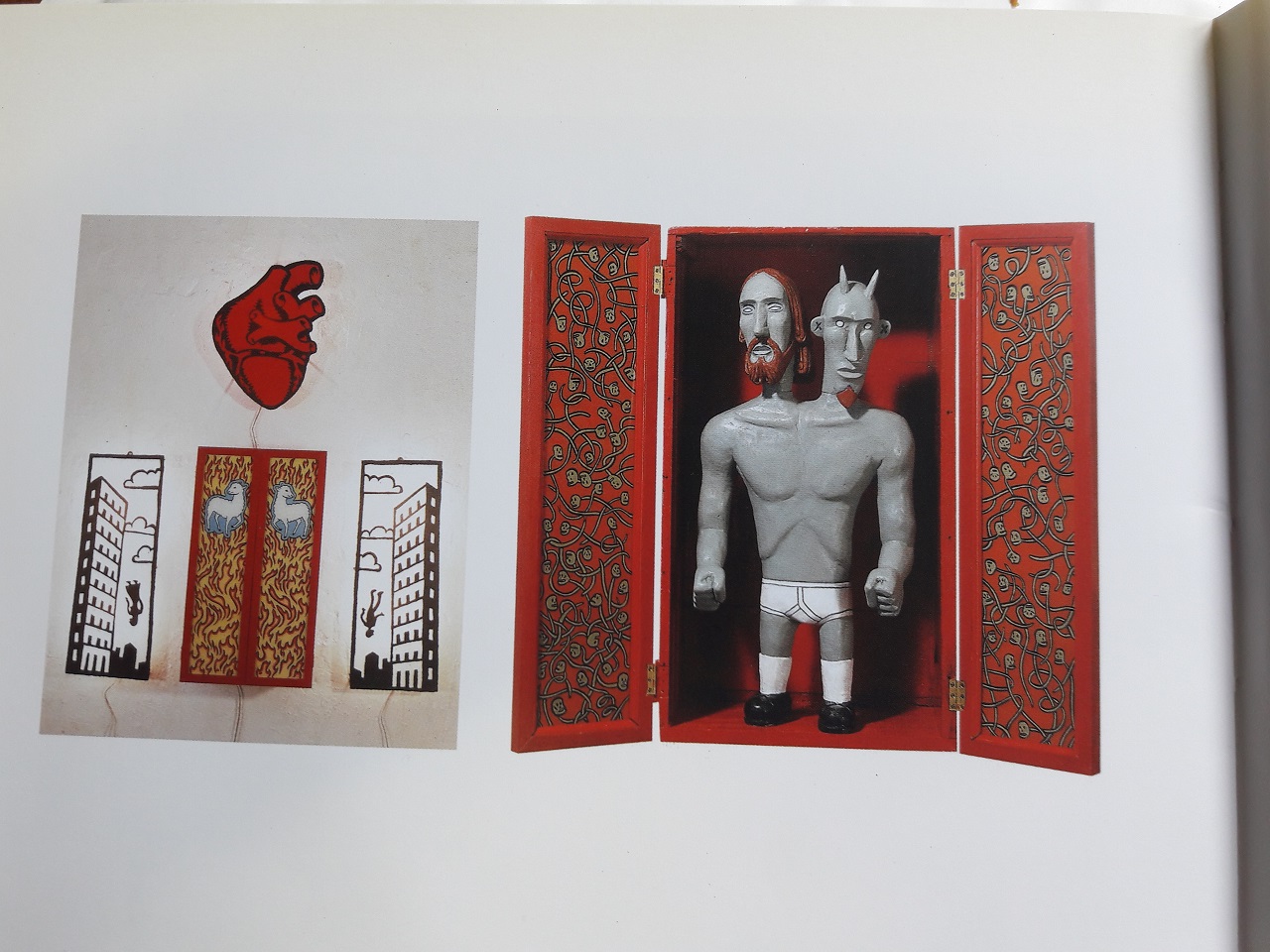

- Conrad-Botes-Voodoo-

Art fairs are all about trade. The first round of trade is the floor space that is typically sold at square metre rates; the more you buy, the more you get. Those who are able to invest in large chunks of space are guaranteed a good position, which means right at the mouth of the entrance of the host venue. If ever the old adage, ‘position position position’ has value, it’s right here. The second tier of trade is the artwork that is sparingly displayed in innovatively designed booths. These presentations may seem minimalist in approach, but overall the selection on offer is diverse, across all modes of expression and obliging that dictum of something for everyone.

See it as a temporary stage created by art fair organizer for a host of actors, including gallerists, artists, collectors, cultural activists, agents, critics, socialites, art professionals, book and magazine traders – and a public. The stakes are stacked high for the major players involving a hefty upfront investment with an unknown outcome. It is reported that sales made at major international art fairs can cover a gallery’s operating costs for several months, but the opposite is also true, mostly for small to mid-tier galleries: the cost in attending an art fair can wipe out their operating budgets for several months afterwards. Media reports now suggests that the major international art fairs are considering sliding scale rates, the more you buy, the more you pay, to retain the participation of smaller and particularly younger galleries, and for good reason. It is after all the young galleries that will keep the art fair model afloat in the coming decades. Either way, art fairs have become the principal sites for trade in the gallery business, and if you’re a player, this is the game.

If you want to know a nation, look at the art that it produces. But if you want meaning then looking is not enough. A visit to Cape Town in February now offers an all-encompassing experience of both looking and finding meaning of not only the art that is produced by one nation, but also on the continent and elsewhere, including Europe and the Middle East. It is a month when Cape Town’s economy is largely driven by its creative industries, its museums, art galleries, art foundations and pop-up initiates along with several major international events including the Investec Cape Town Art Fair.

The seventh edition of this art fair opened just after midday on Valentine’s Day and our beautiful city had both water and power. It’s worth mentioning this, because there have been days when the city had neither. An overall first impression was the lack of a major anchor in the form of a central installation that locates the fair in the global south. I am not suggesting that the fair platform assumes a socio-political responsibility. However, given the dire state of affairs globally, it feels like a missed opportunity not to do so – and giving a nod to the maxim, namely, that art is a tool, if not for change, then at least to conscientise a public, not forever perhaps, but at least for a day. Most visitors to art fairs find them overwhelming, which in my opinion increases this need for a central anchor, something on which to pin an entire experience.

Artist Manfred Zylla told me on the opening night that his favourite piece was a short film by Clement Cogitore (France) and Borna Sammak (United States) screened inside a shipping container. The dance performance, set to an 18th century opera-ballet soundtrack, he felt, was a powerful comment on the present day socio-political battles experienced across the globe. I didn’t see the film, but I appreciated its comment which added to my feeling that art fairs can no longer operate in a vacuum, that global issues need to form a part of its larger narrative. Maybe I should add that most art fairs offer a Talks Programme and it is often here where contentious issues of international importance are raised and debated. Although the Cape Town Art Fair does offer such a programme, it is presented off-site and, in my opinion, creates an unfortunate disconnect between talk and trade.

As much as I admire this young art fair’s attempt at internationalism – to showcase a diversity of work that represents the forefront of contemporary art from Africa to the world and the world to Cape Town – it felt over-subscribed with galleries from Italy (perhaps because an Italian company owns the fair?). South African collectors are known for supporting locally produced work, and have a preference for investing in what they know and whom they know. Collecting trends in South Africa also point to an eagerness to acquiring works produced by artists originally from the continent and/or currently working and living on the continent – a shift, largely stimulated with the opening of the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary African Art in Cape Town. Bearing this in mind, the number of galleries from Italy outnumbered the total number of galleries from elsewhere on the continent, outside of South Africa. I should, however, declare at this point that my involvement at this fair was through a young Italian gallery whose presentation included the work of one South African artist.

I can think of two reasons why this fair is set for growth – firstly, it is young enough to develop into a platform that is more representative of if its locality; and secondly, it is fulfilling a core function, meaning participating galleries are making sales, perhaps not swimmingly, but enough to keep this fair afloat.

The secondary market is now part and parcel of any art fair week – a South African auction house, Strauss & Co, upped the ante on just how this is done, and for a second year in a row, hosted an auction in a spectacular site at the harbour. A full-on event complete with an exhibition of the inventory on offer, a big screen flashing images of the lots, a currency converter, a raised platform for those waving a paddle in one hand and a cellphone in the other and a champagne bar, all magically dropped into a large rough and grungy structure.

Things went without a hitch, until an installation piece by an artist known to me flashed on the screen – but was introduced as a work made by two artists. The artist who is not the artist is connected, and this is probably where the auction house fell hook, line and sinker into this gross mis-representational mess. These two artists, through Boogie Lights, a collaborative commercial project with its own identity, manufactured a series of objects that revealed a combination of their strengths, and as such, never linked either of their individual artist’s names to this project. The lot, dated 2001, includes three collaborative pieces as components in a larger installation. It is well illustrated in international exhibition catalogues as an autonomous work credited to one artist. The accompanying text in this catalogue mentions the name of the artist who is not the artist as manufacturer of the collaborative pieces, and then continues to cite Robert Drew’s widely circulated image taken on 9/11 as the source for the depiction of falling figures. The artwork’s real history is located outside of the 9/11 event narrative. It was produced months before September 11, and its only connection to the event is that it bizarrely happened to be documented on that day.

Look at it this way – eyebrows will definitely be raised, if in twenty years from now, a Jeff Koons work pops up on auction as a Koons & Da Vinci because someone at an auction house recognized the Mona Lisa in the background. One can also understand the added value of text in auction catalogues, bits of unknown histories, like the time when a valuable painting was found in a London kitchen where it long functioned as a notice board, or when a painting, in this same auction catalogue, is referred to as ‘sumptuous’. Text like that does not interfere with the meaning of the work nor does it effect its value, and even if it is not true, it remains inconsequential – describing an artwork as “sumptuous” is a personal opinion after all. But when a 9/11 narrative is attached as meaning, not only is it consequential, it is deeply disturbing and in this case, not even true. The text in the auction house catalogue is credited to one of the most respected arts writers in South Africa, giving it gravitas – that too, is intrinsically linked to value.

There is no argument that auctions are platforms where value is established, investments are realized, records are set, and histories are made. Like art fairs, these are high stake environments, and the correct information is crucial, critically so.

Art fairs and auctions are both in the business of selling art. The one primarily deals with living artists, and the other, primarily but not exclusively with those long departed. In the case of this lot, a contemporary auction, the living was mingling in the crowds and spotted the error. But as this story reveals, there is not much value in error spotting. Either way, art fairs and auctions are the main economic drivers of the arts industry; artists, whether dead or alive, need them.

This story has a Hollywood ending, scripted by the auction house. The artist who is not the artist is extremely happy with the co-authorship. The artist who is the artist is very happy with the text, and only requested a minor or “wee little correction” (not my words, theirs) for the work not to be placed within the September 11 narrative.

However, the client’s opinion was never sought, not once, during the entire process of to-ing and fro-ing, with exchanges getting increasingly heated. Eventually an ‘apology’ was presented, reading like this: “Sorry that we did not meet your expectations as far as the text and content are concerned.” It is an unfortunate use of words, because the only expectation any client has when they release a work onto auction is that it will sell, and that it fetches a good price. As for text and content, the expectation is that the information published is true, not fictionalized, nor re-invented. And if there are errors, I am sure, an expectation will arise for it to be corrected, according to the client’s requirements, not the artist’s.

So, if you really want to know more about a nation and its art, look at the pictures in the auction house catalogue, by all means, but if it is meaning that you are after, do a Google search. At least one auction house has now made it clear that not all expectations for text and content can be satisfied.

Who else needs a glass of champagne?

Heidi Erdmann is an independent curator based in Cape Town. She sold the lot mentioned in this story in 2001 to the owner who released it onto this auction.

( Images supplied by the Investec Cape Town Art Fair)