It’s Eurovision Time 2019!

May 13, 2019

The Magical Worlds of Mamuka Dideba

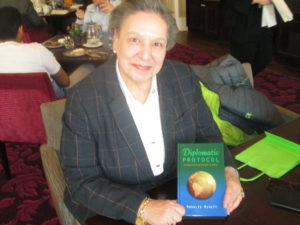

May 29, 2019In the era of Trump, Cold War and undiplomatic language, the art of diplomacy is getting lost. As an antidote, we consider a new book by Rosalie Rivett. Professor Nabil Ayad writes a review for DANTE.

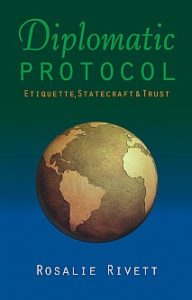

Rosalie Rivett’s Diplomatic Protocol – Etiquette, Statecraft & Trust is an essential handbook both for those new to the diplomatic corps and for those who have been involved in it for many years. In addition, the book provides useful information for members of the international press and the general public who are attempting to navigate the troubled times that we are encountering in world governance today.

In the 17th century, when diplomacy started to take its current form, the knowledge and skills of the diplomat at that time were as follows: he (it was always a male) would be a trained theologian, well versed in Aristotle and Plato, an expert in mathematics and physics, an expert in civil law, able to speak and write Latin, Greek, Spanish, French and German, and with a taste for poetry. It was still mainly matrimonial diplomacy that was utilised to create ties between nation states; there was no mention of the word “protocol”.

Increased information, better communication, enhanced transportation, and advanced technology have resulted in serious and wide-ranging challenges arising in an increasingly complex world. Rivett has created an indispensable guide which speaks to these challenges in a timely and provocative manner.

The delicate art of diplomacy is surely more vital than ever; the world needs diplomats with training and vision. The author provides details as to how diplomats can reflect on the lessons and methods of the past while applying enhanced knowledge, enlightened attitudes and technologically advanced systems in an increasingly complex world.

She points out that diplomacy is adapting to changing circumstances. For example, it is true that governments and international governance are being conducted very much on a regional basis. Diplomacy is the soft power underlying every nation’s ambitions; without diplomacy, the breakout of wars would increase, peace treaties might never be negotiated or signed, and trade missions might flounder. She highlights the importance of diplomatic protocol which, it has been said, is the etiquette of diplomacy. In her words: “It is one thing to want to strike up a conversation, but quite another to know how the dialogue should begin.”

Today, the role of a diplomat is demanding and essential to the well-being of the world. Rivett observes that there are “new styles of diplomacy” – less rigid, more interactive, and more immediate, and that these new styles create a demand for diplomatic training. For example, if diplomats are going to negotiate on behalf of their home countries, they should be aware of history and of the previous treaties which, although still forming the structure of the international law, may need to be changed or updated. With pressing issues such as preserving the environment and mitigating the risks of global warming, existing agreements may have to be altered; she believes that as a result it is essential for diplomats, whether they are arguing about toxic emissions or new boundaries on the Law of the Sea, to be aware of all the arguments and implications. With proper training, diplomats will be able to approach their tasks equipped with the necessary background knowledge. But without that background and training, they will not be aware of the long-term implications of the words that are spoken, the actions that are threatened, and the smouldering situations that are left unresolved.

Like the March Hare in Alice in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll’s fantasy novel, we seem never to have enough time and always to be rushing. Rivett reflects on this situation, saying: “Sadly, what no-one has time for today is time. In a world of instant results and instant solutions, negotiations are conducted at pace… there is now an immediate news conference and perhaps an ill-considered sound bite. The comment may play well to the domestic audience, but it does not always lead to a resolution of the difference between two parties. Time is no longer on the diplomat’s side, it would seem.” She observes that diplomacy has had to change, and change quickly: “Each country will still have its own agendas, which in large part are purely domestic, but now many of the agendas, such as policies on the environment, climate change and health development, are international.”

She goes on to describe the realities of working as an ambassador today. Diplomacy is no longer a nine-to-five job, ambassadors have to contend with tight budgetary restrictions, and heads of mission have to be encouraging and considerate because the essential role of the diplomat is to persuade; they must not only persuade their staff to go the extra mile, but more essentially persuade the host nation about the benefits to themselves of the sending nation’s policies.

Religious differences have been a major source of conflict among nations. Rivett addresses the concomitant challenges that diplomats face, and refers to the increasing number of religion-related conflicts we have witnessed since the start of the 21st century. She says, “The very purpose of diplomats is dialogue, keeping the lines of communication open, and understanding the protocols, traditions – and most importantly the history and culture – of these many faith groups, which will increasingly be at the forefront of the diplomatic agenda. Religious diplomacy, the protocol and sensitivity required in exchanges between faiths, to encourage peaceful dialogue, will demand the very best ambassadors and high commissioners.”

Another area which is undergoing change is business protocol. The decision by the British to favour Brexit and the decision by the U.S. to reject the traditional Washington power brokers and vote for Donald Trump, an outsider to the political establishment, have changed the political dynamic of the West. How will the new order change the way that business is conducted? How will diplomacy adapt?

Perhaps the greatest threat to peace today comes from the Internet and information technology. State leaders and diplomats are frequently captured on smartphones making statements which can be embarrassing to their home country. These statements are shared with the world via Twitter or other instant messaging systems, as though they represent the policies of the state. In addition, confidential files have been stolen and leaked to the Internet, as in the case of Wikileaks. Therefore, it is extremely important for all diplomats to understand the role and the power of the Internet and information technology. Rivett asks: “Who is in charge? Are politicians being run by the information flow, taking decisions based on what they actually know, or merely on what they have heard or read online?” She continues: ‘As we are now living in a world of social media, this form of public diplomacy has become an extension of traditional and conventional diplomacy.’ How, she wonders, would the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 have played out if President Kennedy had been obliged to give a running commentary on his tense negotiations with Nikita Khrushchev?

Rivett has accomplished much in this publication. She has developed a handbook of the essentials for those in the diplomatic service filling a vacuum in the literature on professional diplomatic protocol and statecraft. But she has done so much more: she has brought to light many issues that confront all of us who are living at this pivotal point in history. She has created an awareness of the necessity of rigorous, well-structured international training which will enable diplomats to adapt successfully to major changes at the top of the international agenda.

Professor Nabil Ayad is Founder and Director of the Academy of Diplomacy and International Governance, Loughborough University London. DIPLOMATICPROTOCOL – Etiquette, Statecraft & Trust, Whittles Publishing, is priced £25.Information: http://www.whittlespublishing.com