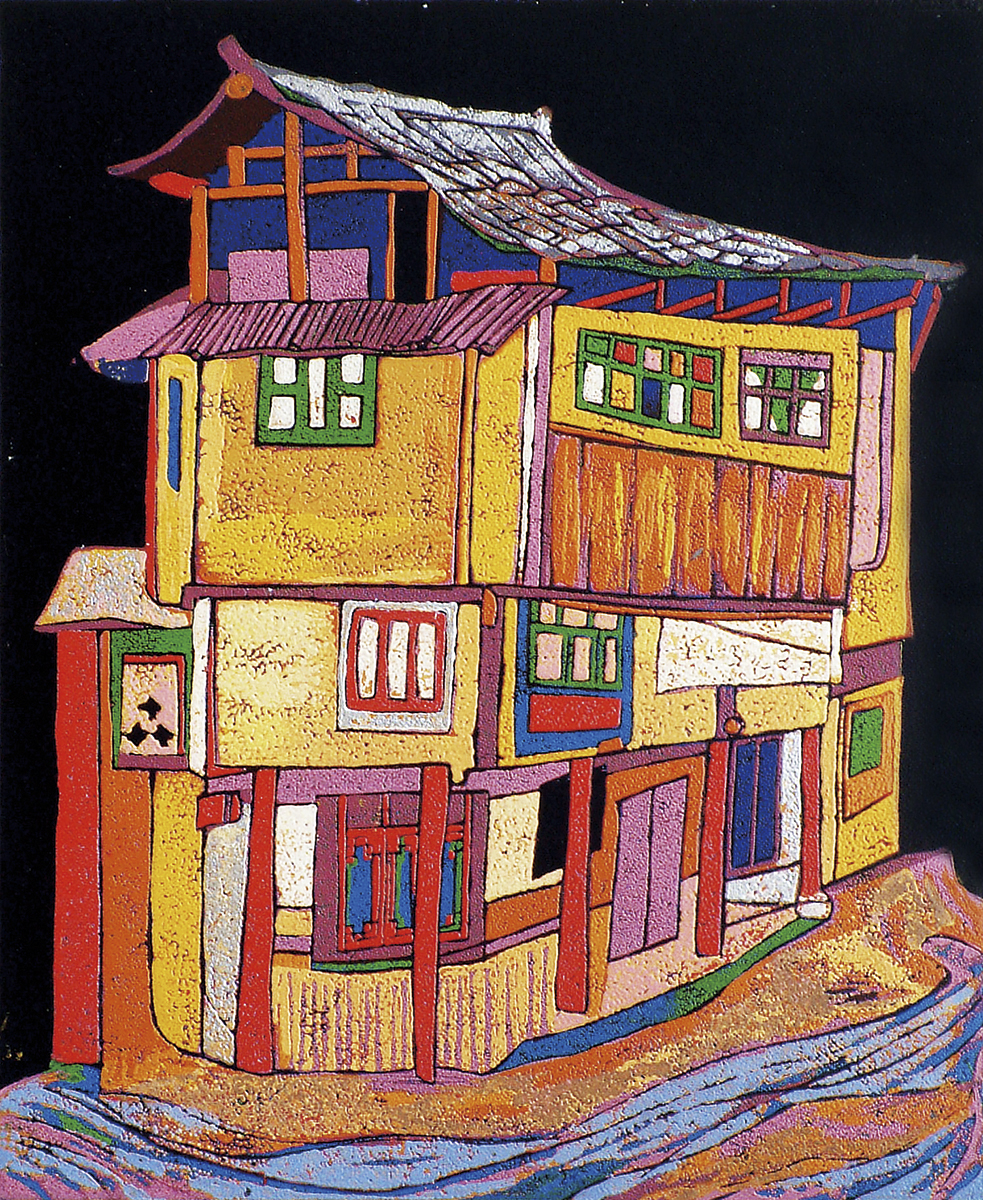

Celebrating the Display of Chen Li’s work at The British Museum

June 3, 2019

The Knights and the Princesses. In the Grenfell Tower.

June 15, 2019From her Kashmiri grandfather dying in the Great War to being brought up and educated in the UK, Riffi Khan repays her gratitude by urging others to realise their dreams through education, as she herself has done so spectacularly.

A twist of fate, a single moment in time which changes the course of a person’s life path. That’s what happened to me, my family history and destiny. Taking me from a life laid out with limited possibilities to one full of magic and experiences beyond my ancestors’ imagination.

My father was born and raised in the Rajput clan, descendants of ‘Raja’ or King, who hold an elite status amongst the clans who have lived more than 300 years in the Kashmir mountains, now in Pakistan. Mountain life was tough but simple, growing what they needed and living off the land. These were hardy people. It’s no surprise that is where the British went to recruit men to fight in the British Indian Army. You need a lot of men to rule empires. My dad’s father, my grandfather, Akbar joined the Rajput Warriors Regiment in order to earn a regular wage but eventually found himself fighting the Japanese, in arguably the most hellish conditions, on the Burmese front in the Second World War. It was there that his best friend, ChaCha Gazan, watched him die next to him, from gun shrapnel in 1945. My grandfather was 28 years old. Leaving behind a daughter and an eldest son, my dad, who never knew him and whose prospects without a father and provider looked bleak.

ChaCha Gazan did what a good best friend would, he decided to bring my father to England under the Commonwealth which had given him a home. A chance to give my dad a step up and steer him to a better Iife. After all, his father had died for the British in their war. He paid for my father’s ticket and sort of adopted him, helping him settle in, firstly with him in Birmingham. Then soon after he found him work in another town. ChaCha Gazan was married, but his wife and kids were still in Kashmir, he brought them over a few years later. I remember how excited my father was when there was news of ChaCha Gazan visiting us. He was the only person I saw my father admire and whose words he heeded. For him he finally had a father figure to look up to, a man who taught him the importance of dressing well and polishing his shoes – as only an ex-army man can.

This twist of fate led me to being born in England. I was an Asian girl with automatic access to education. Education for a girl was unheard of in that part of Kashmir at that time. you don’t need to be educated to milk goats or raise children. Which, despite a few girl schools being built, is sadly still the case today. Boys are encouraged to study but girls aren’t. Unsurprisingly illiteracy rates in Pakistan are shockingly around 67%.

Fortunately, I was able to – indeed, expected to – go to school. Anyway it’s mandatory in Britain as well as being completely free. This undervalued and under-appreciated gift of knowledge for me and my classmates transformed my life and that of my four siblings. I’ll be honest I didn’t appreciate it at the time as I was not a good learner. With little money and coming from a community that didn’t believe in educating girls, my mother still encouraged us to study. Though I struggled as a child academically, all five of us managed to graduate from university, with my brother becoming a doctor, first in a hospital, then as a GP.

I like to think our grandfather is looking down rather proud that we turned his tragedy into something good. My sister became the first girl from our region in Kashmir to go to university, my brother being the first boy, followed by my younger sisters who now work in PR and event management.

As for me, I dug deep, pushed myself hard to study and eventually gained a degree in Economics from the prestigious London School of Economics. Instead of going into the City and banking, I accidentally fell into the wonderful creative world of television – producing and directing some of the biggest TV shows from prime time documentaries to “I’m A Celebrity Get Me Out of Here”.

It was education that gave me the opportunity to change and create my own future and provided me with those unlimited possibilities to make my dreams come true – or at least have a good go at realising them. What is exciting is going on this intrepid journey. Mine took me into places beyond my wildest dreams. Filming inside the Queens Gallery at Buckingham Palace, lined with Vermeers and Vandykes, inside the Van Gogh and Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam was unexpected bliss for an art lover like me. As a result of being a TV format consultant I’ve been lucky enough to have flown around the world for work, stayed in countless beautiful places and I’ve met celebrities such as Diana Ross and Lionel Richie and countless more.

All thanks to ‘the gift of free education” from an ordinary comprehensive state school, which made my life rich with experiences and fulfilled my soul. With it, came the freedom to pursue dreams beyond the limiting straight jacket of my female ancestors.

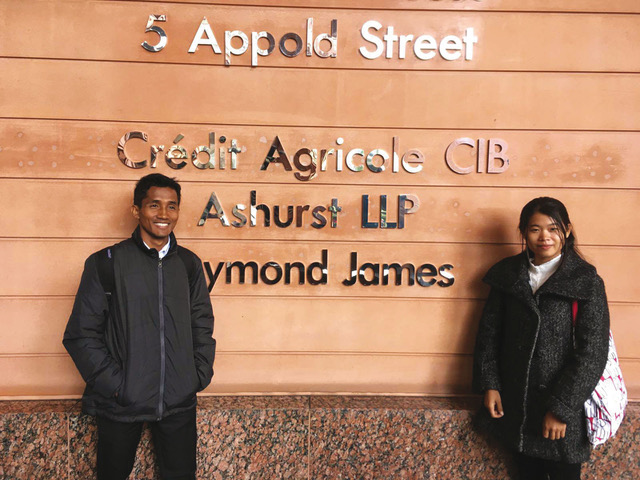

Once I’d set up my own company, Sunflower Productions, it was sheer serendipity that my first two stories, in a series of interviews called ‘Real Life Fairytales’, featured two young Cambodians who broke out of the cycle of poverty by means of education. At 13 years of age Chhengtay fought with her parents to continue her education instead of following her sisters into Thailand’s ‘waitress’ industry. Education is an unnecessary luxury when you’re foraging for food each night and need money to eat. The other story concerned Kosal, a happy-go-lucky young man with a refreshingly positive mind-set – “I don’t care about a new uniform, it’s old for them but new for me,” he declares as he shares his hunger to learn. This is the same country, where under the Khmer Rouge, education was deliberately wiped out.

By 1979 the regime had systematically killed nearly two million of its educated citizens. This led to doctors, academics, lawyers and all manner of professionals being murdered, turning the country back into a state of subsistence living and poverty. As a result there were no longer any role models of what could be achieved with education. Despite this, Chhengtay and Kosal, through sheer determination, won scholarships from a UK based charity, Children Of The Mekong, which even brought them over to London for three months. I was fortunate to film them, fittingly – or ironically, depending on your point of view – in the luxurious suite belonging to a UK bank chairman.

By 1979 the regime had systematically killed nearly two million of its educated citizens. This led to doctors, academics, lawyers and all manner of professionals being murdered, turning the country back into a state of subsistence living and poverty. As a result there were no longer any role models of what could be achieved with education. Despite this, Chhengtay and Kosal, through sheer determination, won scholarships from a UK based charity, Children Of The Mekong, which even brought them over to London for three months. I was fortunate to film them, fittingly – or ironically, depending on your point of view – in the luxurious suite belonging to a UK bank chairman.

And so it comes full circle. These stories are about you, me, us. I’m grateful now for my education, something of a luxury we may take for granted or feel entitled to. Most of all, I’m glad these two stories will be watched by young Cambodians who will see someone who looks like them living in the same poverty, transforming their lives and making their dreams come true and helping others in their country. The charity is screening the films in schools here in the UK, so western school kids are able to seize the day and find the strength to find their way to better life, too.

These simple stories are a real-life example, proof of how we can continually improve our lives, at any age, anywhere in the world, if we want it bad enough. No one said making dreams come true was going to be easy, but the rewards I’ve discovered are worth it.

I’m grateful to my parents, for bravely allowing me and my sisters to go to university. Education is a complete game changer, allowing us, in turn, to help others who come after us. Never take your education for granted – it is a luxury in some parts of the world so seize the endless opportunities it offers you and amake a difference. Chhengtay and Kosal have against all the odds!

You can watch Chhengtay and Kosal’s heart-warming stories at www.sunflowerproductions.co.u