The Knights and the Princesses. In the Grenfell Tower.

June 15, 2019

Pandoro or Panettone? Let Us Eat Cake!

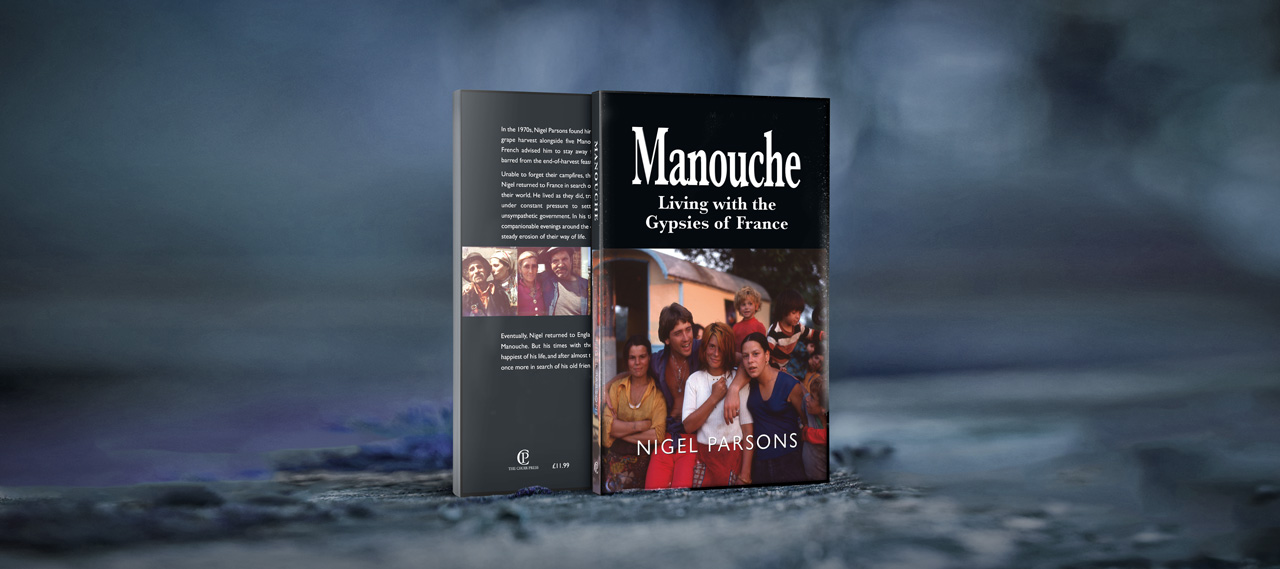

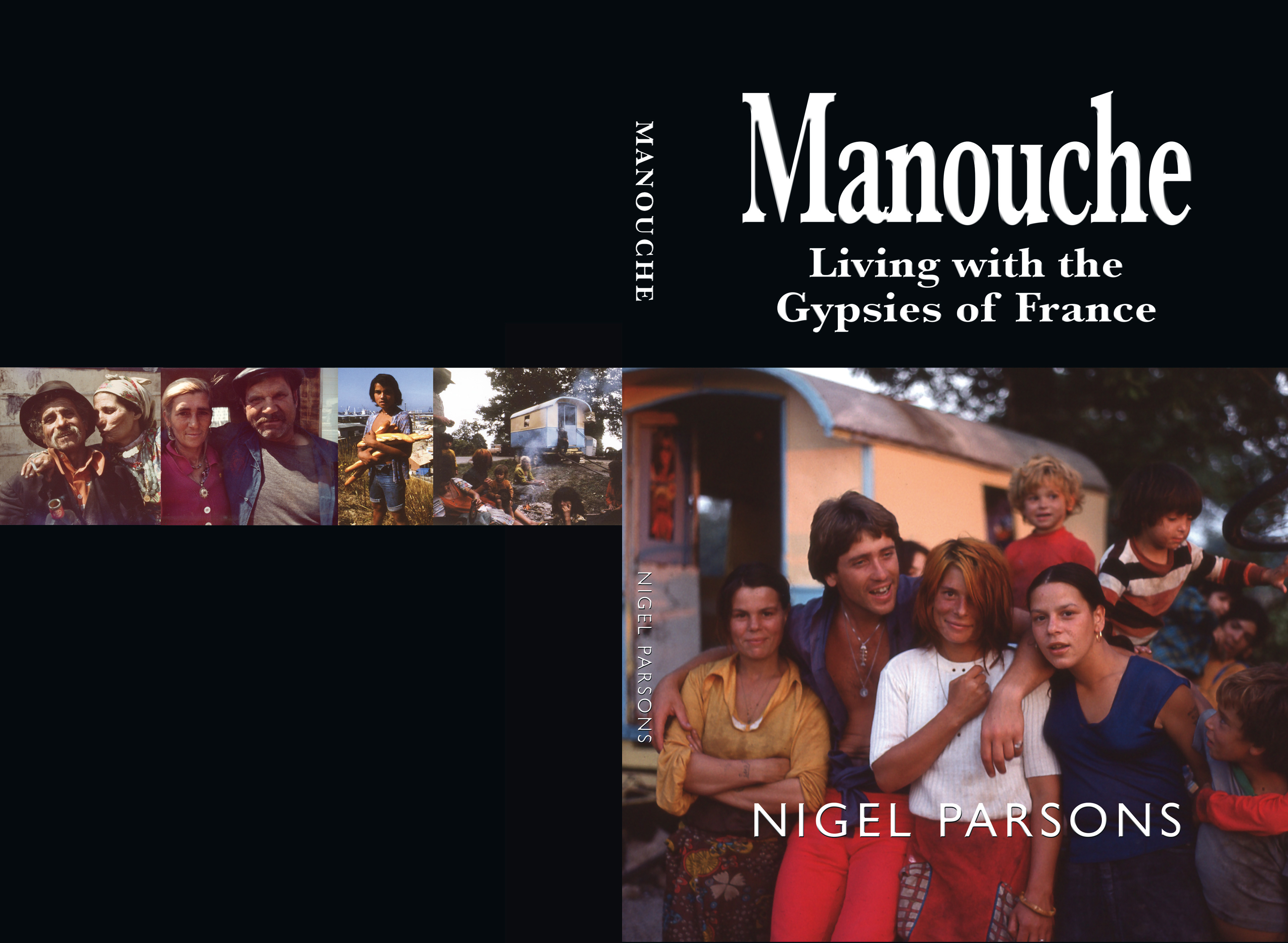

December 3, 2019Finding himself at a dead end after retiring from a high-flying career, DANTE contributor, Nigel Parsons is inspired by an old photo album and goes in search of long-lost friends.

Zozo with caravan 1979

Andy Warhol talked about everyone having their fifteen seconds of fame, and if that’s true then I think I had a bit more than my fair share, maybe even thirty seconds, as I somehow became a bit of a high flier in the world of broadcasting, being a part of the launch team for several international TV channels, including being the launch Managing Director of Al Jazeera English and TVC Africa.

But then, inevitably, came RETIREMENT. A lot of people dream about it but often it’s not as easy or as good as it sounds. After more than forty years in work, I was disorientated with all that free time. For a year and a half I did nothing but read incessantly, play a few games of golf, drink too much and get depressed. Until one winter’s day, grey and pouring with rain and the London sky feeling like it was only a couple of inches above my head, I decided to start sorting through the thousands of photographs I’d accumulated over the years.

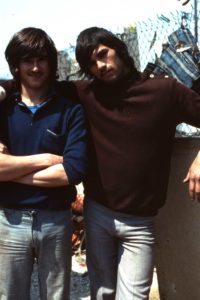

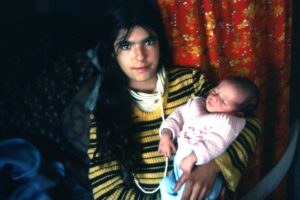

It wasn’t long before I came across my old photos from the time I lived with a group of Manouche gypsies in France. I’d met them while working on the vendange, the grape harvest, near Bordeaux at the end of the 1970s, and we’d met up again the following year and I fell in love with their free spirit, their campfires and their songs. At the end of that second harvest they invited me to join them, and so I did and lived with them for more than three years, learning their language and customs, their fear and respect of shape-shifting spirits, travelling with them from spring until autumn, working the harvests – and picking up several godchildren along the way!

It was a wrench to leave them in the end but they were under pressure to give up their travelling life, the vendanges had become mechanised, and I had no means of support. Although we stayed in touch with regular visits for several more years, we eventually lost contact when I went to live in South America. Those were, of course, the days before the internet and mobile telephones. But sorting through those old photographs I realised that my time with the Manouche was one of my happiest. After rummaging through the garage I also found my old notes from that time, and I decided to write about the experience. At least it was something to do.

At first it went well, but there was a problem. During a pre-Christmas lunch with a friend in Brighton last year, he asked me how the story was going to end. I realised I had no idea, and the way it was going it would just peter out around the time we lost contact.

The vendange 1970, L-T Mochi, Chocote, Roupenho, Beudjeu & Casque

‘You’ve got to have an ending,’ my friend remarked. ‘Think about it.’

He was right, and as I pushed my pasta around the plate I realised there was only one solution. I had to try to find my gypsy family again, after a gap of almost thirty years.

I tried Google Earth looking for caravan encampments in our old winter quarters by the docks in Marseille, but nothing came up. I tried search websites but there was virtually no information about the Manouche. There seemed nothing else for it but to search for them in person.

I no longer had my van but I did have a beautiful old Triumph T-100 Bonneville motorbike which had been spending too much time in the garage. I had it serviced, had the carbs flushed and soon it was ready to go. After some unseasonably warm weather I set off at the end of February – which was a big mistake. As soon as I drove off the ferry at Calais it started raining, and it deluged for the next three days as I battled my way south to Marseille, where the sun finally shone again. I was cold, wet and miserable for most of the time, but there was no turning back.

Pantoon in front of the new houses, Marseille 1980

In Marseille I searched the old dockyard area, showing my photographs to anyone who would take the time to look, and discovered there was still a Manouche community living in what could only be described as slum conditions. I found it eventually and nervously rode in to suspicious looks, stopping by a group of red- eyed men drinking beer.

‘Are you Manouche?’ I asked.

‘We are, what do you want?’

Again I showed my photos and told them how I’d once lived with them and reeled off a list of names, and one hit a chord.

‘Pantoon? Yes he still still lives here, up the hill,’ one man said. ‘But the others are gone.’

I was deflated. Pantoon had been a teenager when I lived with them, but my closest friends seemed to have disappeared. But Pantoon was a start and I found him living in a wreck of a caravan resting on flat tyres with windows held together by tape. He didn’t recognise me at first but when I told him who I was he burst into tears and gave me a huge hug and we went through the old photos together.

Author with god daughter Monique, Charentes 2019

Word spread and soon dozens of others came to look through them, some crying. It would’ve been perfect if, in the meantime, some of the kids hadn’t ripped open my saddle bags and stolen my camera and my laptop which contained my draft manuscript. I was saved by a tough young man who’d only been five or six years old when I last saw him, but one of my old photos was of him with his mother and myself, and he vowed to get my laptop back. And he did – he was feared amongst the community. ‘Nobody likes to mess with him,’ said Pantoon.

Author with Ghuno & Paquili 2019

Apart from Pantoon it seemed the rest of the old group had decamped to central France, near one of our old stopping places outside the village of Le Dorat, north of Limoges. We phoned them and they were speechless. Hundreds of miles later I found them, and slept soundly in a caravan again. They’d left the slums of Marseille and bought their own land where they now live – not at the bottom of the pile, but parallel lives, with their language and customs intact, even though their children now go to school and can read and write. They are happy, even if they no longer travel carefree as before. And now we talk every week on our new mobile phones.

The whole experience has at last found its ending and can now finally be told. My finished book “Manouche – Living With The Gypsies Of France” is published by The Choir Press and available in paperback or in e-book format from Amazon.