Arditti’s brilliance inspires us again with his new novel. The Anointed.

April 17, 2020

Dantemag and Belstaff

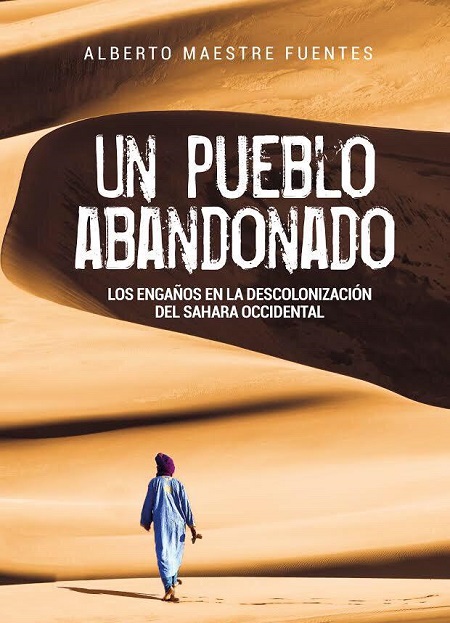

November 25, 2020The Spanish Empire was one of the first great colonial empires and one of the largest. Here Professor Alberto Maestre Fuentes talks about its former colony in Africa, The Spanish Sahara, which is still the last colony standing on the continent, and Spain’s irresponsible behaviour towards its decolonisation and freedom.

What had been a Spanish province right up until the end of 1975, is nowadays the last colony left in the continent. On top of that it has the “distinction” of being the largest geographically and population-wise of those territories awaiting decolonisation. Of the seventeen UN Non-Autonomous Territories, the Western Sahara, situated right next to the Canary Isles and with so many historical ties with Spain, is a complete unknown, not only to most of the world but also to Spaniards themselves.

Spain, which in the sixties was committed to developing the country and made major investments, would adopt contradictory positions. On one hand it considered the Sahrawis to be Spanish to all intents and purposes by virtue of it being a province but, on the other hand, subscribed – in appearance at least – to the UN policy of decolonisation.

There is no getting away from the fact that at the very moment Spain maintained Spanish Sahara was another Spanish province, it was beginning the full process of decolonisation in Africa. The official debate inside Spain at that time constantly referred to the “undeniable Spanishness” of the Western Sahara, since the assumed strategic importance of the country in the defence of the Canary Isles was still an issue.

This nationalist talk, which, in the middle and late sixties was backed up with visits by high-ranking offiicals to the Spanish Sahara, was in direct contrast to the line Spain adopted for the international community, namely, that of supporting self-determination for the Sahrawi people.

At the same time Morocco, ever since it gained its independence, had dreamed of creating a “Greater Morocco”, incorporating Western Sahara, Mauretania, large parts of Algeria, together with an area of Mali. Indeed it had signed up to an agreement drawn up by the Organisation of African Unity, which, in order to avoid potential territorial disputes between African states about to gain their independence, accepted without any reservations the inherited colonial borders. But it was now beginning to put pressure on Spain to unilaterally relinquish Western Sahara.

To that end, it didn’t hesitate to employ different strategies, ranging from terrorist acts by groups the country financed and introduced into the Sahrawi territory, to extending their territorial waters, seizing fishing vessels, ramping up its claim to Ceuta and Mellila, as well as engaging in intense and aggressive diplomatic activity.

Spain, when it realised it couldn’t hold to its policy of claiming the ‘Spanishness’ of Western Sahara, finally committed to carrying out the UN resolution and called a referendum on self-determination but in effect it would cave in when faced by the final act of major pressure from its feared Moroccan neighbour.

The “Green March” would force Spain to immediately renounce the commitments it had made. Its overriding and sole concern was not to prejudice its relations with Morocco and to save face with the UN, as Solis, ministerial representative of the Spanish government negotiating with King Hassan II, would admit afterwards.

Many years on from the Spanish getting out and relinquishing their responsibilities, Western Sahara still finds itself split in two. One part – the richest and largest – is under the control of Morocco, where the Spanish language has been eliminated in favour of French and any remnants of Spanish culture erased. In these so-called occupied zones there has been a complete and systematic damnatio memoriae ( cultural airbrushing). This is in direct contrast to the situation in the areas controlled by the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic ( recognised by more than eighty nations) and in the Tinduf encampments where Castilian Spanish is the official language along with Hasani, and which stresses its ties with the old country.

“An Abandoned People. Deceits in the Decolonisation of the Western Sahara”, based on my doctoral thesis, for which I consulted and studied newly discovered documents and carried out interviews, demonstrates how, for Spain, its bilateral relations with Morocco took absolute precedence over any commitments it had made to the UN and the Sahrawi people.

Abandoning these commitments – and thus being indirectly complicit in violating international law and human rights – and not giving visibility to the Western Sahara in order to avoid conflict with Morocco in any shape or form, altogether just creates an image of extreme weakness on the part of Spain.

The Western Sahara continues to exist as a colony and Spain could play a decisive role in it no longer being one. The question is – is there the will to do so?

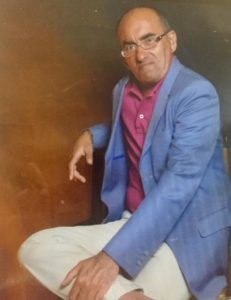

Alberto Maestre Fuentes, Professor of History at Barcelona University, has contributed to a wide variety of publications and is also a member of the prestigious Josep Termes Chair Research Group for National Cultural and Political Studies (GRENPoc). His first book “An Abandoned People – Deceits in the Decolonisation of The Western Sahara” was presented to the Spanish Senate in Madrid last June.

TR. Philip Rham

Other books to read on the subject